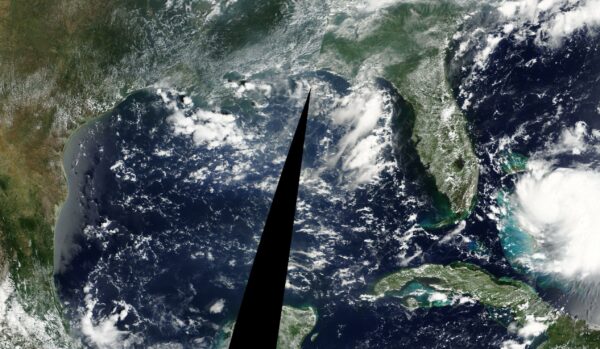

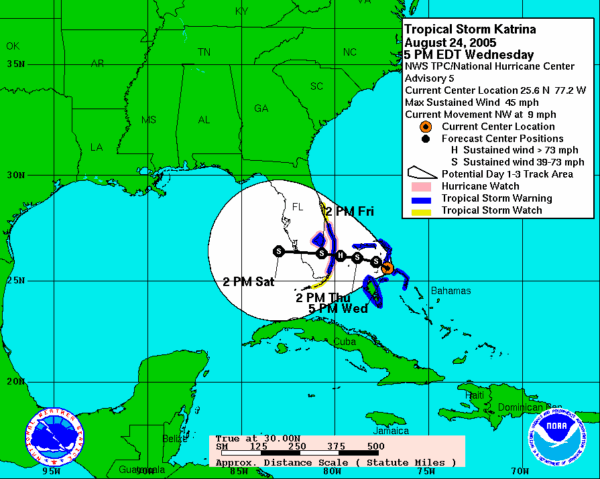

Wednesday, Aug. 24

-

Tropical Depression Katrina is first detected 175 miles southeast of the Bahamas

-

It strengthens into Tropical Storm Katrina as it moves toward the Florida coast.

-

The National Hurricane Center issues a hurricane watch, and then upgrades to a hurricane warning just before midnight.

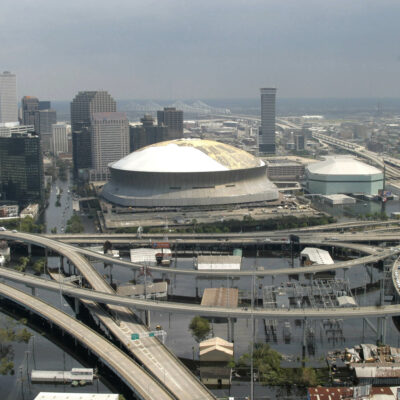

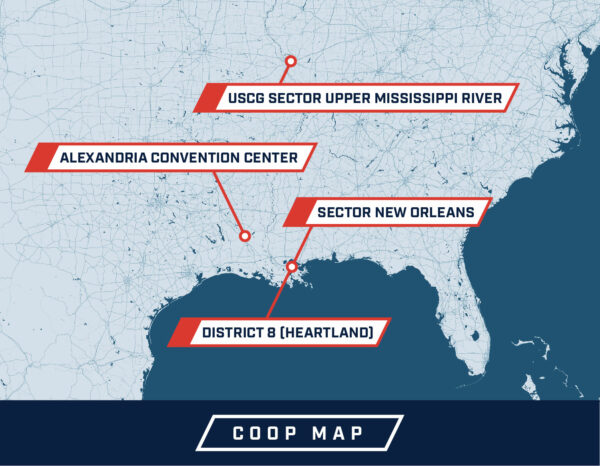

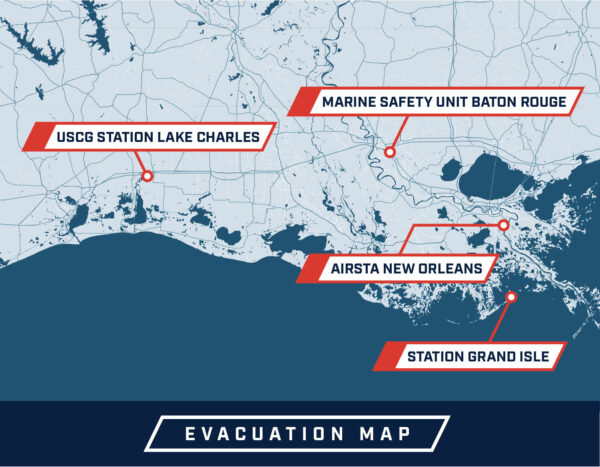

Louisiana’s Gulf Coast region is home to some of the busiest Coast Guard units, all led by Sector New Orleans. The Coast Guard’s entire Heartland District is also based out of New Orleans.

All of these teams’ daily operations came to a sudden halt, as leaders activated their evacuation plans and uniformed members figured out the safest places for their families to ride out the storm.

BM2 Ronald Mancuso, for example, was ordered to motor one of Station Grand Isle’s two small boats up the Mississippi to Baton Rouge.

We got whatever personal items we could.

BM2 Ronald Mancuso: “I was stationed here in Grand Isle. I was a duty coxswain and we were just doing our Coast Guard everyday missions, you know from law enforcement to homeland security; stuff like that. I was actually on duty weekend the Friday they told us that we would be leaving. The XPO came in about 10 or 11 o’clock and got everybody together and we started deciding what we were going to do and who was going and where. And about midnight they made the decision that we were leaving at 6 o’clock the next morning with the two 41s to go up to Baton Rouge and I was one of the coxswains on that boat. Most of our families lived on base and we were waking up our families telling them to start packing. We got whatever personal items we could. I knew I was leaving at 6 in the morning and that I wouldn’t have a chance to get any of my personal stuff taken care of. My wife was able to get clothes for her and my daughter, as much as possible, and she was able to take the pictures off the wall and she got all of our important papers and loaded the truck up. But that’s all she was able to get. Then she and my daughter went and stayed with family in Baton Rouge.”

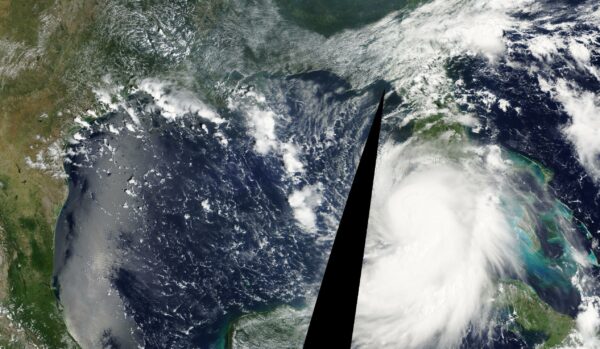

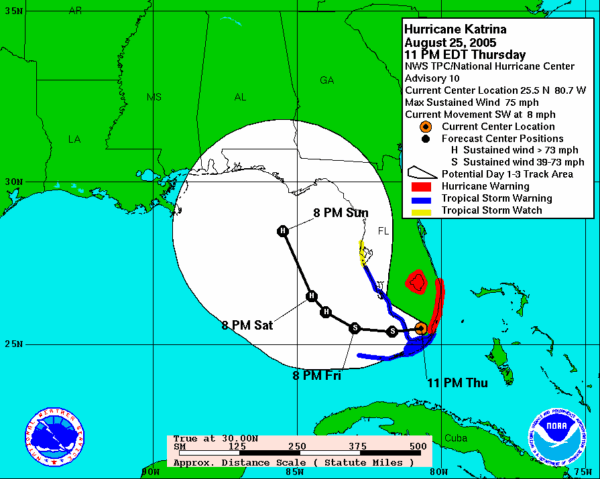

Thursday, Aug. 25

-

Hurricane Katrina makes landfall on Keating Beach, south of Fort Lauderdale, around 6 a.m.

-

The eye actually passes directly over the National Hurricane Center, which reports a wind gust of 87 mph.

With Katrina set to make initial landfall in Florida, the Coast Guard’s Southeast District (then known as District 7) activated its Incident Management Team (IMT) and sent liaison officers to county Emergency Operation Centers (EOCs) to help coordinate relief efforts. This is a tried-and-true approach for coordinating with local, state, federal and tribal authorities during a disaster response, and proved its value once again during Katrina.

Weather conditions deteriorated throughout the day. District Southeast responded to three vessels in distress, hoisting 9 people to safety – the first rescue of thousands to follow in the coming days.

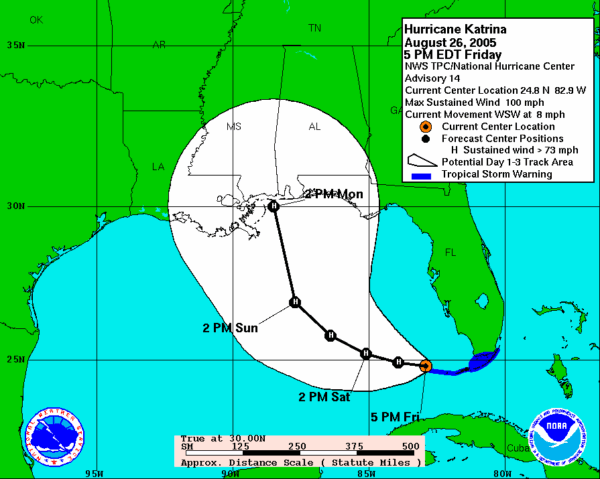

Friday, Aug. 26

-

Hurricane Katrina is now a Category 2 hurricane.

-

The National Hurricane Center shifts the storm’s possible track from the Florida Panhandle to the Mississippi/Alabama Coast.

-

Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco declares a state of emergency, which activates the state’s emergency response and recovery program.

As Katrina made its way into the Gulf of Mexico, Air Station Clearwater began a search and rescue (SAR) operation that would last 27 hours. At 7 a.m., the air station received a report of an activated Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) from the fishing vessel Mary Lynn. There were three people on board the sinking vessel, located 85 miles west of Key West, Florida, very near the eye of Katrina.

The station dispatched a HH-60 Jayhawk under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Craig Massello. The hurricane-force winds made the 210-mile trip take longer than anticipated, and the helo was forced to refuel at Key West. When Massello finally located the Mary Lynn, he lowered his rescue swimmer, AST3 Kenyon Bolton, into the water off the vessel’s stern. The waves were 40 feet high. During a harrowing 30 minute rescue that included a brush with a shark, Bolton got the three crewmen safely on board the helicopter. They touched down at Clearwater at 10 a.m. on Saturday morning.

About 300 miles away, while Massello was fighting Katrina’s winds, Sector New Orleans was having a party. Coast Guard members were celebrating the service’s newest command, created from merging three smaller commands. The new sector’s commanding officer, Capt. Frank Paskewich, hoped the morale event would give everyone a chance to relax and mingle.

“Captain, we need to talk.”

CAPT Frank Paskewich: “We had a great cookout right over here at the Southern Yacht Club, located just around the corner from us. They handed me a microphone, and I thanked everybody for their support and said they had done such a tremendous job that they needed to take the afternoon off and go enjoy a nice weekend and that we’d see everybody on Monday.

No sooner had I put the microphone down, someone came running up and said, “Captain, we need to talk. You need to see the latest trajectory. Hurricane Katrina is coming off of Florida and the revised trajectory shows that it’s going to impact Louisiana.”

At that point, I had to cancel that liberty. From that point on it was ready, set, go.” (Quote edited for length.)

Go to the full-length interview for an abstract and transcript.

Paskewich implemented the Sector’s Continuity of Operations Plan, which involved relocating everybody to Alexandria, La.

Around that same time, Rear Adm. Robert Duncan was facing similar decisions. He ordered his people and assets to evacuate up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, while he would stay “forward-deployed” rather than going with the crews.

“I wanted to replicate ‘Apocalypse Now’ with Coast Guard helicopters,” Duncan said. “Remember that movie with all those Hueys coming in all at once? I wanted to darken the sky with orange helicopters.”

Duncan contacted the governors of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama to inform them of the Coast Guard’s capabilities and his plans for handling the response.

The most important part of the pre-hurricane planning was to ensure that Coast Guard units survived the hurricane’s impact and be instantly ready to conduct relief and rescue operations. Aircraft went to Air Station Houston and other airports out of harm’s way but close enough so they could follow the hurricane closely as it moved inland. Boats were moved up the Mississippi River to safe anchorages while personnel made sure family members were evacuated.

CAPT Robert “Bob” Mueller, the Deputy Sector New Orleans Commander, noted that “we had units scattered all over Southern Louisiana … because we were afraid if we had one safe haven or two safe havens and they got hit, they could be damaged beyond repair or we’d lose our resources.”

One of those critical resources was Aviation Survival Technician Lawrence Nettles, called “Noodles,” by his friends. (By the end of the response, even the Coast Guard Commandant was using the nickname.) Nettles was based at Air Station Clearwater. As he evacuated to Lake Charles, his wife headed to work at Tulane Hospital.

I left the house accepting that I was going to lose everything.

AST3 Nettles: “Before Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, we were just running around with our heads cut off. Everyone at the station was just packaging and boxing anything and everything that we could and tying it down, and at home I grabbed all my personal stuff. We took our cats to Baton Rouge to my wife’s parent’s house and then I went back to base and flew to Lake Charles and my wife went to Tulane Hospital. She was going to ride out the storm there and I was going to be on the ready crew. Everyone said that the West Bank would flood before anything else, so I left the house pretty much accepting the fact that I was going to lose everything.”

Go to the full length interview for an abstract and transcript.