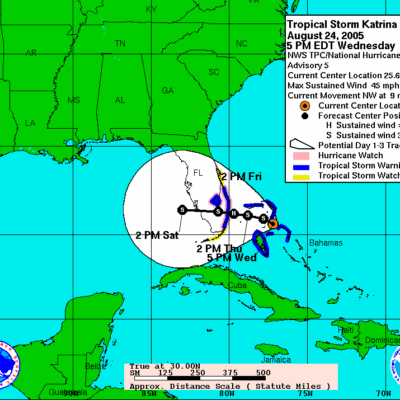

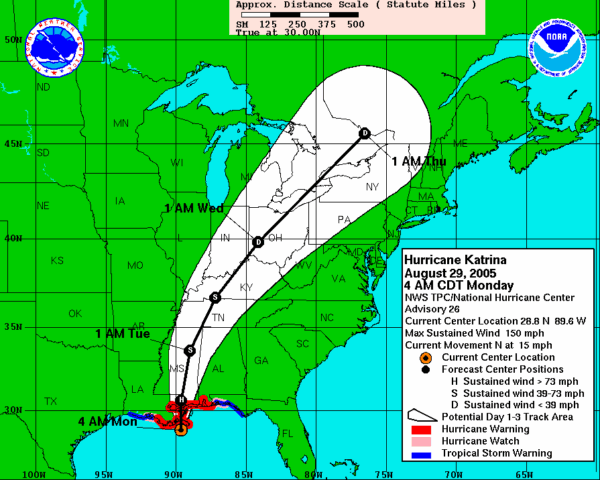

Monday, Aug. 29

-

The Superdome’s power goes out at 5 a.m.

-

Katrina makes landfall in Plaquemines Parish at 6 a.m.

-

By 6:30 a.m., most of New Orleans is without power.

-

Levees begin to be overtopped or destroyed, and water rushes into the Lower Ninth Ward.

-

By 9 a.m., the Lower Ninth Ward is under 6 to 8 feet of water.

-

By 11 a.m., St. Bernard Parish is under about 10 feet of water.

Katrina made landfall in Plaquemines Parish as a strong Category 3 hurricane. Everything she touched was completely destroyed, either by 127-mile winds or the 22-foot storm surge. All power and communications were knocked out. Cell phone service went down.

And then the levees failed.

The 50,000 citizens left in New Orleans, awaiting rescue, were now trapped.

The devastation overwhelmed local emergency facilities, transportation systems and logistical support services. “What you had then was the back-flooding of the city, when the water that got pushed up to the northwest shore of Lake Pontchartrain came back down when the wind reversed and was driven into canals, said Vice Admiral Thad Allen, who was the Coast Guard’s chief of staff. Later, he would be named the Principal Federal Official for the Katrina response.

“I’ve termed it the equivalent of a weapon of mass effect that was used on the city without criminality. In other words, it was Mother Nature instead of Al-Qaeda, but what you had . . . basically a city was taken down.”

Adm. Thad Allen (Ret.)

I knew immediately that the “Big One” had occurred

CAPT Paskewich: I knew immediately that the “Big One” had occurred when the reports started rolling in from my liaison in the city Emergency Operations Center. I was getting reports like, “Charity Hospital flooded; windows blown out; 17th Street Canal breeched; Lakeview: eight feet underwater; 20-foot surge in Bayou Bienvenue; ship Chios Beauty broke its moorings at Algiers Point, now aground on the right descending bank; flooding everywhere.” There were numerous reports of looting. And then I’d get reports from other folks about impact on the waterway; ships adrift, barges run up on the bank, barges which sank, a drydock has struck a tank ship. I went through an entire notepad in that first day from documenting all the reports.

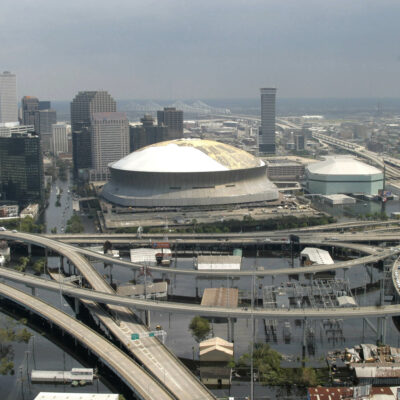

Rear Adm. Duncan flew over the city in a HU-25 Falcon. “It was a very sobering flight. As we came up into the city, we were all kind of stunned by what we saw . . . nothing was above water,” he said. “We’d see steeples. We’d see roofs. And if you look closely, you could see where the telephone poles were – and that would give you some indication of where the road was. The entire Gulf Coast – from Mobile, Alabama to some point west of New Orleans – was blacked out.”

The scope of the damage was almost inconceivable. But as Duncan flew over New Orleans at 800 feet, fighting 60-knot winds, he saw his orange helicopters fanning out above the city.

CAPT Jones and his five helo crews had been waiting out the storm in Houston and Lake Charles. When the winds fell to tropical storm levels that afternoon, they lifted off. Joining up with two other orange helicopters from Air Station Houston, they refueled in Houma, La., and then proceeded to New Orleans right behind the storm.

“It just looked like an atomic bomb had hit the place,” said Capt. Jones said. “Houses just shredded into bits; boats everywhere up on top of the levee, on top of bridges, in the woods; heavy, heavy flooding; none of the pumping stations were working; homes underwater.”

They slowed the helicopter to view the damages. “We began to see persons waving for assistance from rooftops in all directions,” Jones said, and they started getting the equipment ready for hoisting. “We attempted to triage informally by looking for children, elderly people or those whose situation appeared more precarious. Our prime concern for healthy individuals was simply to remove them from rooftops and take them to dry land, with the idea that they could survive until morning and be rendered further assistance then.”

“I observed for the first time all of East New Orleans under water, up to one-story rooftops.”

By 3 p.m., only a few hours after one of the worst hurricanes in the history of the country had devastated New Orleans, the Coast Guard was making rescues. Capt. Jones, LTJG Shay, and the other three pilots immediately started SAR operations.

As they worked, they could see the situation go from bad to something that none of them quite had words for.

“I remember hovering over Lake Pontchartrain’s 17th Street canal, and we watched the levees fail,” Williams said. “I saw the top bricks come off of the levee, then more and more bricks came down, and then the water came through. I watched the interior of New Orleans fill up with water.”

Someone on the helo started taking photos – these became the much-shared photos most people think of when they talk about the levees failing.

Including Williams, there were 28 pilots at AIRSTA New Orleans back then. They flew nonstop Monday and Tuesday.

“The reality is that Bruce Jones and those 28 pilots held the city together for the first 24 hours after the storm passed.”

This could change New Orleans permanently.

CAPT Paskewich: We gather all the staff and the dependents. I tell them we’re about to embark upon a new historical era; that this will be unlike anything we have ever seen, and could change the City of New Orleans permanently. A storm of this magnitude would probably cause incredible devastation. So we will probably have a very, very large search and rescue operation to deal with – particularly in the inner city with urban flooding. We know that we will probably be rescuing lots and lots of people by air – and that at some point we would be rescuing lots and lots of people by small boat. We begin mobilizing small boats from around the country; little John Boats or Flood Punts with small engines on them.

Many of the members knew their own homes had almost certainly been destroyed.

By now, AST3 Nettles was assigned to an HH-65 from AIRSTA New Orleans, under the command of Lt. David M. Johnston. Nettles hadn’t yet talked to his wife, who by now was likely caring for survivors at Tulane Hospital. He hoped that she was safe. The crew received a Mayday call that they traced to a stand of trees in Port Sulphur, Louisiana. Nettles was threaded down through the trees, where he found three survivors along with their three dogs, trapped aboard an aluminum skiff. Nettles then rescued three generations of women – a mother, her daughter, and her grandbaby.

Three Generations Rescued from Katrina's Wrath

Their home had stood since 1876, but Katrina’s storm surge quickly swallowed the second floor. Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina, survivors remember a Coast Guard aircrew rescued three generations of their family.

We heard a MAYDAY by a frantic woman

AST3 Nettles: “On the way in we heard a mayday by a frantic woman explaining to us that her daughter and her grandchild were on a boat and they needed help and assistance. We flew down and we zeroed in on them at Port Sulphur. We found them in an aluminum boat in the middle of a neighborhood underneath some trees. The water was about ten feet high. She explained to us that her daughter’s daughter was a four-month-old premature girl, which is, premature children are very susceptible to any kind of environment. They can get sick very easily. The boat was directly underneath some trees. So they had to lower me down into the water.

“From the water I reached the boat and got into the boat. I made sure everyone was okay. I took the daughter and the granddaughter and put them in the basket. They also had three dogs with them and I put one of the dogs in the basket with them and then hoisted the other dogs up. The hard part was lowering the basket down to me. We were directly underneath tree limbs so they had lowered a trail line to me and they had lowered the basket while I was holding it with the trail line, and quite a number of times the basket or the cable from the helicopter would get caught or wrap itself around tree limbs so I was constantly breaking tree limbs trying to get the basket and cable clear. I ended up taking the basket with the cable, throwing it into the water, throwing myself into the water and having to get into the basket from the water because the boat was not clear of trees. We finally got them hoisted.” (Edited for length.)

First Overflight

CDR Mark Vislay was one of Capt. Callahan’s HH-60 instructors at ATC Mobile. After weathering the storm in Shreveport, he and his co-pilot LT Steven Cerveny flew to Alexandria to pick up Capt. Paskewich and Capt. Mueller, then conducted the first overflight to assess the damage to New Orleans and surrounding areas.

“I saw my first damage – three ships which looked like that had just been tossed ashore,” said CAPT Paskewich. “Then, as we cut across, you could see the massive flooding and the city was completely inundated with water.”

Cdr. Vislay and his crew went on to rescue 15 survivors that night before they had to land due to the flight time restrictions. From Aug. 29 to Sept. 6, Cdr. Vislay flew more than 44 hours. Along with his crews, he rescued 167 storm victims – including 150 from a Days Inn near Lake Pontchartrain. He lowered his rescue swimmer AST3 Robert R. Williams to the roof, where he was met by three men armed with knives, demanding to be rescued first. Like all Coast Guard rescue swimmers, Williams had been trained how to handle struggling people in the water, but nothing like this. He managed to organize the survivors’ rescue by immediate need, ultimately getting all 150 victims off the roof safely.

Rescue swimmer AST1 Willard Milam, a volunteer from Air Station Kodiak, noted the shock of seeing New Orleans underwater. On one of his rescues, he was dropped at night into an open area and saw the surreal sight of coffins dangling from trees. It took him a while to realize that he’d been dropped into a cemetery. Since burials in New Orleans were above ground, the storm surge and levee flooding emptied some of the cemeteries. He referred to this hoist as his “Dawn of the Dead” experience. AST2 Gabriel Sage from Air Station Astoria, another volunteer, also noted that after being deployed near a cemetery the street “was clogged with corpses.”

Station New Orleans

Around 3 p.m., 10 members of Station New Orleans returned after weathering the storm at the home of the station’s commanding officer, CWO3 Daniel L. T. Brooks. (This was a small boat station, at a different site than AIRSTA New Orleans.) Their station, or what was left of it, had been overrun by over 50 people, some of whom had begun looting.

“All of our stuff had been destroyed,” said BM2 Jessica Guidroz, the unit’s senior coxswain. She and others quickly restored order, confiscating weapons, narcotics and alcohol. When they learned one of the visitors was a retired police officer, he was put in charge of security.

“This is our home,” she told the visitors, “and you’re going to respect our home while you’re here.”

Those who chose to stay at the station were given shelter, water and food rationed out from the crews’ own supplies. The Meals Ready to Eat (MREs) were occasionally replenished by Coast Guard C-130’s. Toilet facilities were non-existent.

After securing the station, Station New Orleans launched its small boats. Crews began conducting urban search and rescue operations through flooded city streets littered with downed electrical lines, broken sewage pipes, ruptured gas lines and submerged obstacles cars.

After working for 14 to 18 hours a day for 19 days, BM2 Guidroz was finally relieved for a few days. She, like most of the personnel who lived in the area, had lost her home and her belongings. “I lost everything,” BM2 Guidroz said. “And even though I wanted to break down, I had to try to maintain my composure to keep these guys focused.”

‘They’re shooting at us’

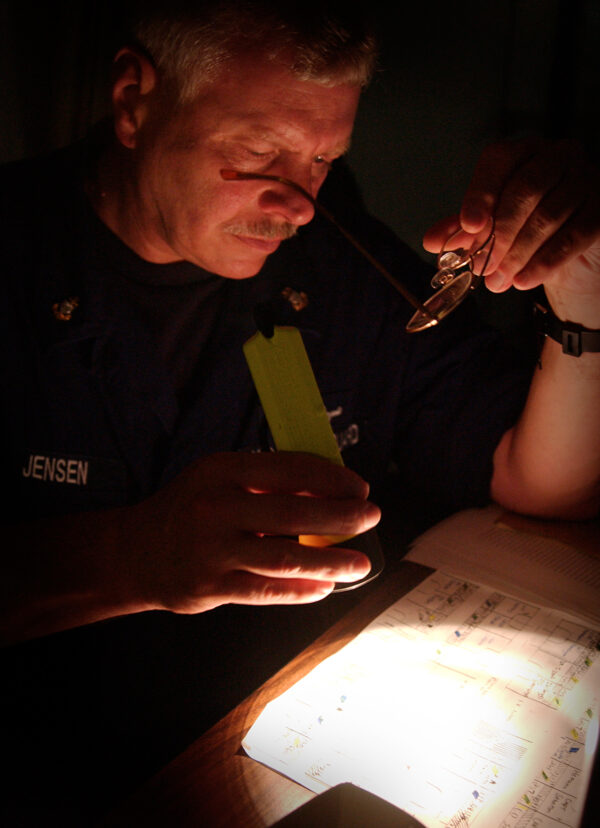

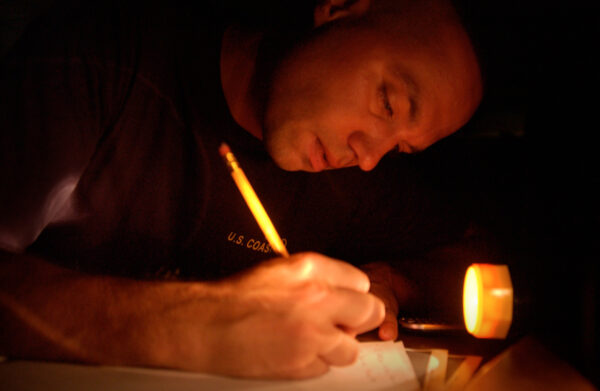

Every night, Cmdr. Jimmy Duckworth, a reservist, create tomorrow’s operational plan: logistics, key rescue targets, manpower and assets. His No. 1 job, though, was helping his members get through the response.

“There was a time when one of my lieutenants came up and said, ‘They’re shooting at us.’ We gathered everyone together, and you could feel – it was like a cake that deflated in an oven. The adrenaline was just go, go go, save ‘em save ‘em save em. And all of a sudden, ‘Who could shoot at the U.S. Coast Guard? How could this happen?’ I will never forget that.”

Thank God we didn’t drop the baby

AMT1 William B. Williams, a flight mechanic from Air Station Cape Cod, said one hoist brought it all into focus for him.

“I remember this one time I was hoisting a father or maybe a grandfather with an infant – the child couldn’t have been more than three or four weeks old – and he was so scared. I’m hoisting the man up, and before he even got to the cabin he’s trying to get out of the basket,” said Williams, who was operating the hoist from the helo’s cabin. “So I’m pushing on the top of his head, because if he gets out he’s going to fall, and we’re at 150 feet. Then he sat back down and he just hands me the baby from underneath the aircraft. I’ve got one hand on the hoist button and one hand on the cable. So I had to drop the hoist or grab the baby.”

A trainee in the cab saw the unfolding crisis. Reaching out, he grabbed the infant and pulled him safely aboard. “Thank God we didn’t drop the baby.” (Edited for length and clarity.)

No level of training can prepare someone for these situations. And most – if not all – Katrina responders would find themselves dealing with the psychological impact for years to come.

MSST 91112 New Orleans

Air and shore operations were frequently halted for security reasons. Roving gangs of looters, many armed, made the situation surreal and very precarious. The rescuers needed protection. Once again, the Coast Guard supplied the answer.

Coast Guard personnel arriving from outside the region armed themselves with weapons from the stations. MSST New Orleans, under the command of LCDR Sean Regan, was told, ‘I can’t tell you what you’re going to do exactly but go down there and do it because we need security. You’re highly trained for this. Go down there and take care of our people.’

Initially, they protected the city’s first responders and prevented complete chaos. They escorted supply convos and provided armed escort for boat crews. Later, they guarded the crews repairing levees and dewatering the city.

Through all of this, Coast Guard members tried their best to avoid the toxic stew of floodwater throughout New Orleans. “You tried not to get in the water if you didn’t have to. But if you’re pulling somebody in out of the water, you’re going to get wet,” said LCDR Daryl Schaffer, who launched one of the first rescue boats from ISC New Orleans. “During the first day maybe there weren’t quite as many contaminants out there, but you could still smell the raw sewage. The scent was in the air. The rotting food hadn’t really started out yet. That came a couple days later when the waters receded. Remember, there are cars underwater there, oil is going to leak and you could see the sheens on top of the water.” Schaffer was one of many Coast Guard members who voluntarily exposed themselves to contaminated water in order to keep saving lives.

The risk was worth it!

Coast Guard helicopters converged on New Orleans and began plucking survivors off rooftops. There was no need for a systematic grid system – pilots who approached the area immediately saw those in danger spread across the rooftops of the city.

More than 50,000 city residents were trapped in their attics or on their rooftops while fetid water lapped at their feet. Temperatures and humidity were incredibly high, with the heat index reaching over 100 degrees.

As darkness set in, “hundreds of flashlights could be seen flashing and waving for assistance over the city,” Capt. Jones recounted in his after-action report. Above them flew a small handful of orange helos from AIRSTA New Orleans and ATC Mobile.

Jones eventually stopped flying, and went back to assess his station. He arrived home to a heavily damaged AIRSTA New Orleans.

The first order of business was to get the power back on, so they’d be able to refuel helicopters. Jones turned to his electricians mate, EM2 Rodney Gordon. The heat was so bad that Gordon could only work on the power at nighttime. “So of course there is no light, so you’re working with a flashlight pretty much stuck in your mouth,” Gordon said.

The Navy’s nearby fuel farm had also lost power – preventing refueling of all the National Guard, Air Force, Air Guard, Coast Guard, Navy/Marine Corps, Army Reserve units at the base. The Navy asked for support, remembers Capt., Jones, “and it was Petty Office Rodney Gordon from the U.S. Coast Guard who went over and got that thing working again, thereby providing fuel to hundreds of aircraft over the next week.”

Fueling the Response

Meet EM2 Rodney Gordon, who was determined to keep the lights on and aircraft fueled at Air Station New Orleans.

As EM2 Gordon was wrangling the power back on at the darkened Air Station, HH-60 pilot CDR Patrick Gorman wasn’t ready to call it quits for the night.

He and the small handful of Coast Guard pilots decided they needed to keep making rescues – which meant flying in a flooded urban environment in near total darkness. It also meant flying into the bag. Jones concurred.

“The risk was worth it,” LCDR Gorman said.

He and the other pilots donned their night vision equipment and continued to drop rescue swimmers onto rooftops. In the first nine hours after Katrina came ashore, those seven helicopters rescued 137 people.

“The sorties were. . .just around the clock. We just slapped new crews in the planes and sent them back out,” said Capt. Callahan, of ATC Mobile.

Rear Admiral’s Duncan’s vision of “a sea of orange” helicopters coming to the rescue had come true.

Editor’s Note: This package was developed from many sources, including an article written by Mr. Scott Price, the Coast Guard’s former historian; oral histories gathered by the Coast Guard historian’s office; imagery from DVIDS, the National Archives and Records Administration; and never-before-seen photos and videos that current and former Coast Guard members sent us from their personal collections. This history is dedicated to those responders’ devotion to duty, courage, humanity, and most of all their selflessness.