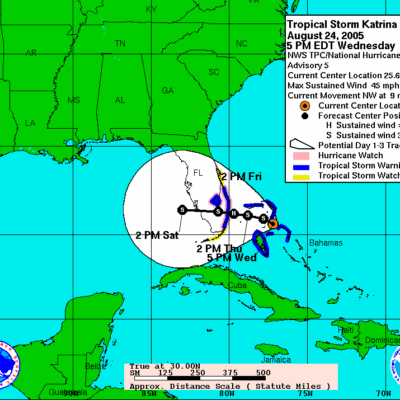

Saturday, Aug. 27

-

By 5 a.m., Katrina reaches Category 3 intensity.

-

At 10 a.m., officials in St. Charles Parish, St. Tammany Parish and Plaquemines Parish order mandatory evacuations.

-

At 11 a.m., Heartland District stands up its Incident Management Team.

As the hurricane moved closer to Louisiana, the District’s assets were out of harm’s way. In Alexandria, the district set up an alternate Command Post in the Louisiana Hotel and Convention Center, with phone lines, computers, and hotel rooms.

“I get word out to the industry that it’s time for them to hunker down, to take necessary precautions,” Paskewich said. “I tell them that by Sunday, if the storm continues on its track, I’ll [close] the entire river to vessel movements and cargo operations.”

It’s time to hunker down.

CAPT Paskewich: “At the 0800 meeting on Saturday, it became very apparent that this was a storm of tremendous strength and that it was headed this way. We decided we needed to evacuate not only our low-lying units but to start getting our folks here in New Orleans out of the area. heads up to our alternate command post in Alexandria. They get the Command Post set up with phone lines and computers, set up hotel rooms, etc. I get word out to the industry that it’s time for them to hunker down, to take necessary precautions. I tell them that by Sunday, if the storm continues on its track, I’ll down the entire river to vessel movements and cargo operations.”

Coast Guard leaders were all-too-aware that New Orleans hadn’t yet told residents to leave. The city issued its first voluntary evacuation order at 5 p.m., urging residents in particularly low-lying areas, such as Algiers and the 9th Ward, to get a head start.

Although members were taking the storm seriously, many assumed they’d be back home soon. BM2 Mancuso’s crew, safely moored in Baton Rouge, decided to stock up on the essentials – food, water, ice.

We may need to stay on the boats a few days

BM2 Mancuso: “We left Grand Isle around 6:30 on Saturday morning. When we arrived in Baton Rouge, we moored up next to tugboats, barges and Coast Guard construction tenders. Then we waited out the storm in Baton Rouge. We were able to go to the store and we all chipped in. We just kind of had a feeling that if it’s as bad as they said it was, we may need stay on the boats at least two or three days in New Orleans. We never thought it was going to be seven days. We stocked up on drinks and ice and stuff. So we fared pretty good later that week, when the Coast Guard was trying to get water to all of these thousands of evacuees and take care of their own people at the same time.”

At 11 a.m., Heartland District stood up its Incident Management Team. Meanwhile, CAPT Kevin L. Marshall, the District’s Chief of Staff, went to stand up the District’s “away” IMT in the Robert A. Young Federal Building in St. Louis. CAPT Marshall and his staff planned to return to New Orleans in a few days; they ended up staying in St. Louis for over two months.

We became the largest Coast Guard air station in history.

APT Callahan: People realized how big this was going to be, and Atlantic Area Command started channeling forces into ATC Mobile. We shut off the training and turned our instructors into operators. They knew what had to be done and they started doing it. We very quickly became the forward operating base for the entire Coast Guard. At times we had over 40 aircraft and over 1,500 personnel working out of here, which is unprecedented. I mean we basically opened the gates to all the TAD forces that came in and you couldn’t go into a space on this base without tripping over a cot or somebody’s little cubbyhole where they were sleeping. We ended up being the largest Coast Guard air station in the history of the Coast Guard.

Answering the call

Coasties from duty stations all over the U.S. move out to assist with search, rescue, and recovery efforts.

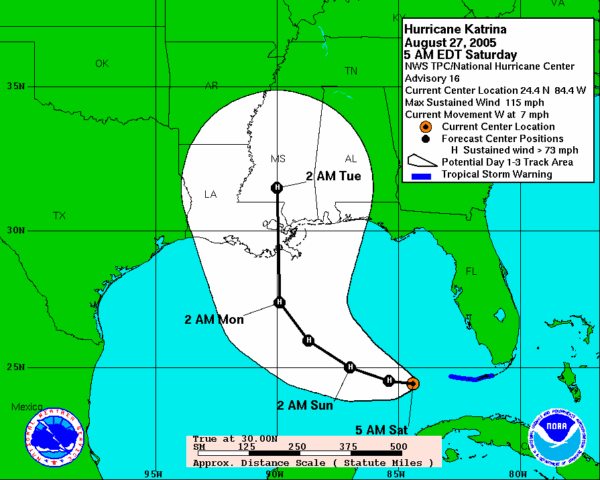

Sunday, Aug. 28

-

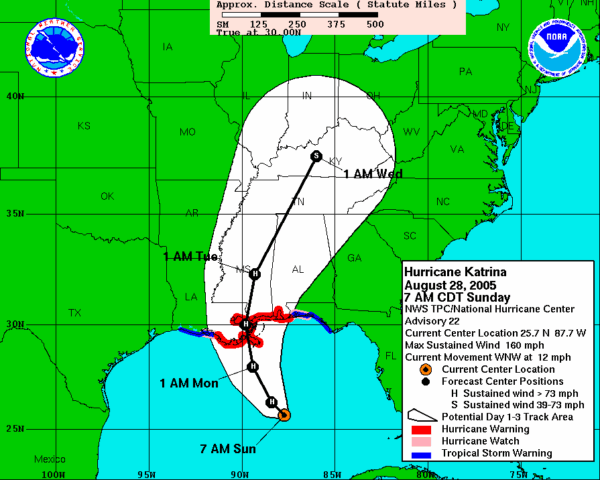

By 7 a.m. Katrina is a Category 5 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 175 mph.

-

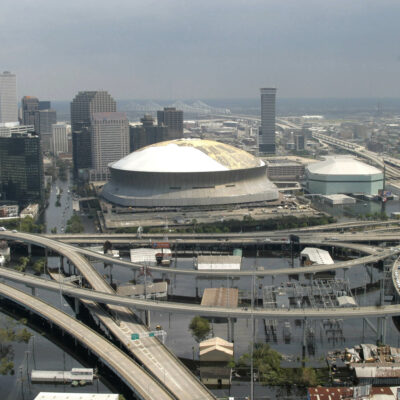

Around 10 a.m., New Orleans declares a mandatory evacuation.

-

At noon, the Superdome opens as a “refuge of last resort.”

-

Coast Guard personnel, helicopters and small boats from around the country start heading toward New Orleans.

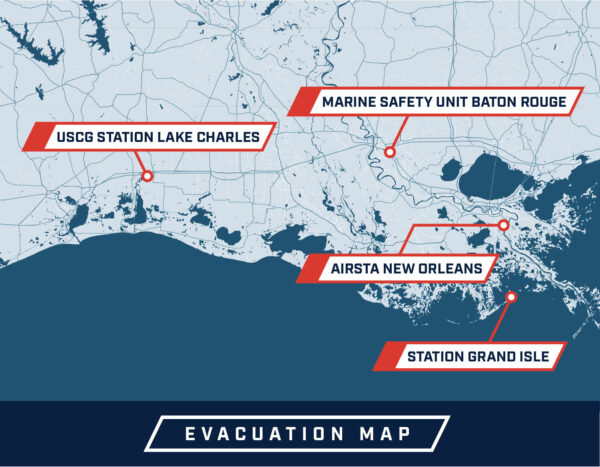

At the Louisiana Hotel and Convention Center, Capt. Frank Paskewich and his crew from Sector New Orleans set up an Incident Command Post (ICP) as part of the broader Coast Guard response. Paskewich was named Incident Commander, with Capt. Terry Gilreath as his deputy.

Paskewich closed the Mississippi River from its mouth to Natchez, Mississippi. He also closed the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, the ports of New Orleans and Morgan City and “all bridges, floodgates and locks” in the vicinity. Vessels that were unable to make it out to sea found a safe anchorage, doubled up their lines and rode out the storm.

The Atlantic Area Commander, Vice Adm. Vivien Crea, directed a surge of reinforcements from all over the country. Aircraft and flight crews from air stations Atlantic City, Cape Cod, Clearwater, Elizabeth City, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, Barber’s Point, Astoria and even Kodiak started preparing to head to Louisiana. Coast Guard Strike Teams were dispatched, along with Port Security Units (PSUs), Marine Safety and Security Teams (MSSTs), Disaster Assist Teams (DATs) from three districts, and DARTs (Disaster Assistance Response Teams) from the Great Lakes District (then known as District 9).

That evening, Rear Admiral Duncan told Louisiana Gov. Kathleen B. Blanco the Coast Guard was ready. “When the winds calm down enough for people to feel safe coming out of their house and if they feel that they need help, I want them to see an orange helicopter somewhere overhead that they can wave at and we’ll come get them.”

The two closest air stations to the affected area, Air Station (AIRSTA) New Orleans and Aviation Training Center (ATC) Mobile, got ready to make that vision a reality.

ATC Mobile would become the staging area for all those incoming members and assets.

Capt. David Callahan was about to do something none of his predecessors had ever imagined: turn the Coast Guard’s only aviation training center into a “full-blown Coast Guard air station.” If the storm kept its current trajectory, his school’s instructors – who usually spend their days teaching young officers just out of basic flight school – would soon be leading search and rescue missions.

Although search and rescue flights tend to get the most public fanfare, nothing happens without working assets. So ATC Mobile’s aviation engineering division chief, Cmdr. Melvin Bouboulis, prioritized maintenance. He wanted as many helicopters as possible ready for SAR operations. His staff prepositioned spare parts and stocked up on aviation fuel. Over the next two weeks, ATC Mobile would run through 210,000 gallons of fuel – enough for two normal months of Coast Guard aviation operations. (CDR Bouboulis also flew SAR missions in an HH-60 for two days, ultimately saving 82 lives.)

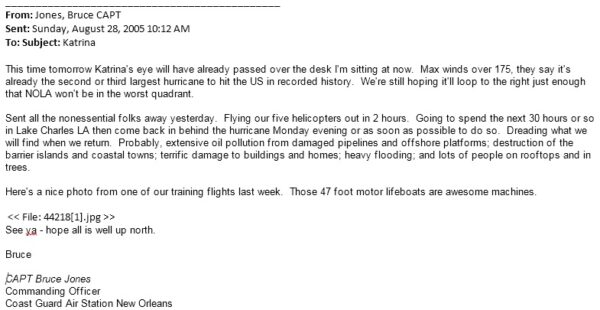

Air Station (AIRSTA) New Orleans was also bracing for impact.

He evacuated all non-essential personnel, but he stayed in place, along with four helicopters and their crews.

“We elected to stay onboard the unit until the day before Katrina hit … to ensure that we could respond to any pre-hurricane SAR,” said Capt. Bruce Jones, the commanding officer. By 2 p.m., with no SAR requests coming in, he finished evacuating the station.

Jones sent two helicopters to Houston; one of them was flown by LTJG Shay Williams, a prior Army enlisted member. AIRSTA New Orleans was his first assignment. “Twenty years later, I still call Bruce Jones Captain,” Williams, now retired, told us in an interview for this piece.

Meanwhile, Jones and two other pilots flew to Lake Charles, where they spent the night monitoring the Weather Channel and trying to get enough rest to fly the next day.

Mississippi & Alabama

While the tragedy of New Orleans received most of the media’s attention at the time, the coastal areas of Mississippi and Alabama too suffered catastrophic damage. The Coast Guard responded in these areas even though many stations were damaged or destroyed.

Chief Warrant Officer Steve Lyons, the commanding officer of Station Gulfport, secured his station and evacuated his personnel to safety on Sunday, Aug. 28. Prior to departing, they responded to two search and rescue calls on Casino Row, saving two lives before Katrina’s landfall. They returned to their station by 7 p.m. Monday evening to a scene of total devastation – Station Gulfport no longer existed.

Disregarding their personal discomfort, complete lack of communications, no restrooms, water or food, Station Gulfport’s crews – assisted by personnel from PSUs 308 and 309 – were underway for 396 hours, running 36 vessel sorties. They saved two lives, conducted three medical transports, and assisted 275 Vietnamese-American fishermen who had weathered the hurricane on their fishing vessels and were stranded without food or water.