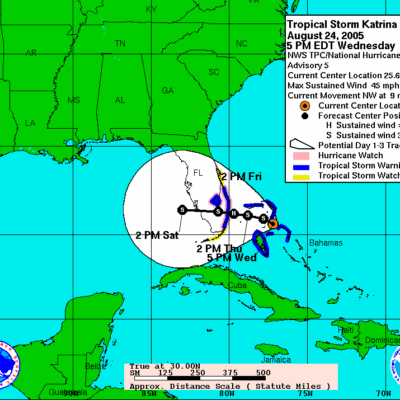

Tuesday, Aug. 30

-

Holes in the Superdome roof appear, and water starts pouring into the elevator shaft and stairwell.

-

Louisiana Gov. Blanco orders the evacuation of New Orleans, including the Superdome.

-

Reports of looting are widespread.

Overnight, a flotilla of Coast Guard vessels – two cutters and eight small 41’ boats – had arrived in New Orleans after making their way down the Mississippi River.

In charge of this hodge-podge brigade was Chief Warrant Officer (CWO) Robert D. Lewald. His ship, the Coast Guard Cutter Pamlico, once got described as “just a big barge that works pylons.”

Second-in-command was Coast Guard Cutter Clamp, which was a tugboat pushing two barges. The cutters’ base average speed was a slow 12 knots, and the crews of the faster 41’s grew impatient.

“We decided that we were going to kind of ease up above the flotilla, because we wanted to be the first ones to see what was going on,” Mancuso said. “We came to what they call the Greater New Orleans Bridge, and it was just pitch black. We could see flames off in the distance.”

It was an eerie feeling

BM2 Mancuso: “We could see people in the two hotels next to the casino. They were trapped on the sixth or seventh floor and they were flashing us with flashlights. (When we finally got somebody over there and they were saying how they’d been there for like three days trapped in the hotel. They couldn’t get out. They didn’t have food or water.) It was a very, very eerie feeling to pull into New Orleans. You know, any other time it’s lit up and you can see all the lights on all the buildings, and it was just pitch black. It was almost like a movie. And then we started evacuating people that same night. …We tied up around 0130 that night, and started again at daylight the next morning.”

CWO Lewald led the flotilla to Algiers Point, where they used Coast Guard small boats to ferry survivors from the flooded East part of New Orleans over to the West side of the Mississippi River.

Learn more about Pamlico and its CO

Into the eye of chaos: River Tender Pamlico in Hurricane Katrina

-

Part I. The Response

The Coast Guard’s response to Katrina was not simply wild improvisation. After gaining significant hurricane response experience during Hurricanes Hugo and Bob, planning, training, and extensive preparations were made for a catastrophic weather scenario. Coast Guardsmen in the field would rely heavily on these plans and preparations. These instructions could be summarized as “don’t wait for permission,” and they became the basis for successful improvisation.

-

Part II. The Clean Up

Katrina destroyed between 70-90% of all the navigational aids on the Mississippi River south of Baton Rouge. With rescue and evacuation activities complete, Pamlico’s next priority was to restore aids to navigation and to make the river more accessible for recovery activities.

-

Oral Histories

Interview: CWO3 Robert D. Lewald, USCG

They moved approximately 2,000 people and provided security at the ferry landing. “There were bad people everywhere.” They had encounters with armed people and had to draw their weapons on several occasions. Lewald was threatened personally and had his own bodyguard for a period.

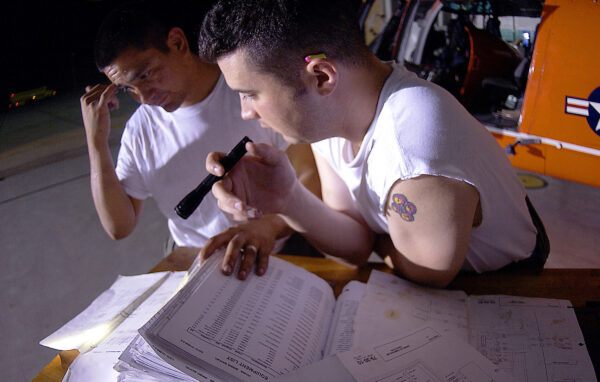

It had not been a particularly restful night for any of the first responders. AIRSTA New Orleans berthing facility and hangar had been flooded, so members slept in the one remaining office building connected to the (failing) generator. They found spaces on the floor, on sofas, on cots or hauled in salvaged mattresses. They slept head to toe. There was no running water.

Capt. Bruce Jones was on the phone into the early morning, trying to communicate the scope of the disaster to Sector New Orleans and the D8 IMT. “I slept curled up on the small sofa in my office, sleeping for a few fitful hours,” Jones said.

His XO, CDR Kitchen, had just laid down in his own office in an attempt to sleep. When he heard ATC Mobile’s H-60s coming in around 3 a.m., though, Kitchen got up to operate the fuel truck so his enlisted personnel could rest until sunrise. At daybreak, Capt. Paskewich wanted to do a flyover for an updated damage assessment. He and his deputy climbed into an H-60 and flew into the city – where AIRSTA New Orleans pilots were still at work.

“We need more helicopters. We need everything.”

CAPT Paskewich: “You could hear the chatter on the radio from the other pilots from Air Station New Orleans who were there; they were saying, “There’s thousands of them. There are people all over the place. We’re picking them up. We need more helicopters. We need everything.” Our H-60 pilot said, “I can fly you around or I can go rescue people.” So he dropped us back off at the Super Dome and then they went on to rescue people. He dropped us off back at the Dome and proceeded to rescue 17 people on his next flight.” (Edited for length.)

As the sun rose higher, the day – like every other for the coming week – became brutally hot. Temperatures hovered around 100 degrees, with no wind and high humidity.

These were the absolute worst-case environmental conditions for the underpowered HH-65B helos and made hoisting not only extremely challenging but often dangerous.

For survivors, the only thing worse than being left in the heat on a field was being left on a rooftop, literally baking in the radiant heat from the attic. Which is why the Coast Guard never stopped.

Help me. Save me.

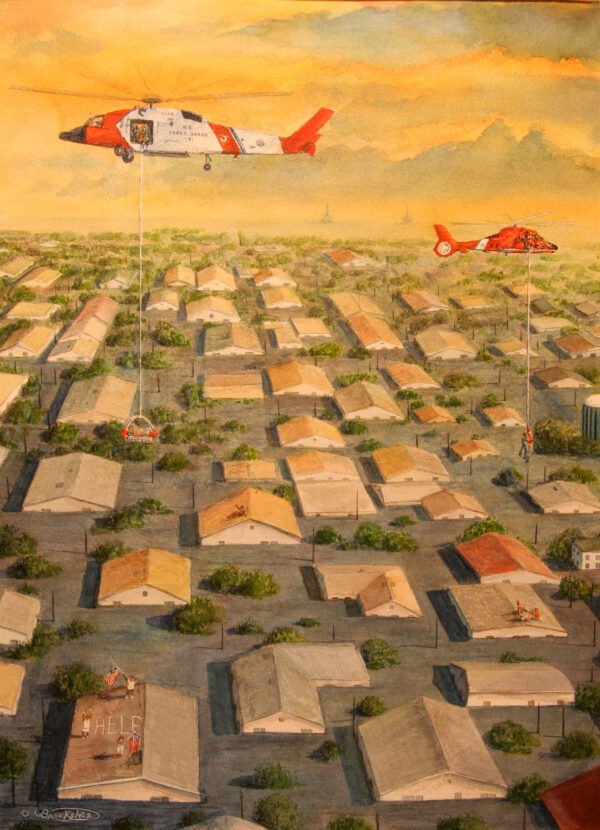

At this early stage, there were so many thousands to rescue that specific, targeted searches were not the rule. Pilots in the air usually had the best info (e.g., “Look – there are another 5 people on a rooftop!”) and made their own tasking on the fly.

The conditions grew steadily worse, and Coast Guard members – from the most seasoned to the most junior – bore witness.

“You know, I expected to see the flooding,” said LTJG Maria Roerick, who had just graduated from flight school. “But I did not expect to see thousands of people standing on their rooftops waving t-shirts or making signs or coming up with all sorts of creative ways to get our attention; “Help me. Save me.” They were everywhere.”

With little to no air conditioning, maintenance and flight crews were under extreme environmental stress while trying to rest between flights, unload gear, or prep aircraft for their next flight.

AIRSTA New Orleans kept losing power, sending EM2 Rodney Gordon up to the roof every time the ancient emergency generator gave out.

Meanwhile, Coast Guard crews from around the country were still pouring in to help. By the end of the response, 5,000 members reported, including maintenance personnel from every Coast Guard aviation unit and air station in the world. “I had folks from all over the Coast Guard that showed up here and knew what to do,” said Capt. Callahan about ATC Mobile.

They all came together

CAPT Callahan: “It was a validation of all the things that we have emphasized for years and years – standardization amongst our crews, recurrent training for search and rescue, maintenance organization. All those concepts, we knew we were doing for a reason and Katrina was the reason.

We had maintenance personnel from every Coast Guard aviation unit, every air station here. They all came together on our hangar deck, formed teams and took care of maintenance for over 40 aircraft for seven days around the clock.

It didn’t take any COs or XOs to figure that out for them. They knew what to do and they did it. Planes came back in this around-the-clock operation and were immediately swarmed by crews of ten or fifteen folks. They’d pull them off to the side, do the post-flights and the through-flights, take care of the discreps and push them back out on the line and get another fresh crew to put into them.

It was unprecedented in the history of the Coast Guard.” (Edited for length.)

AIRSTA New Orleans coordinated a constant stream of tasking from their small Operations Center. At this early stage of the operation there were so many thousands to rescue that specific, targeted searches were not the rule. The situation on the surface was so dynamic that often the pilots in the air had the best info (e.g., “Look – there are another 5 people on a rooftop!”) and were best positioned to provide their own tasking on the fly.

“You know I expected to see the flooding,” said LTJG Maria Roerick, who had just graduated from flight school. “But I did not expect to see thousands of people standing on their rooftops waving t-shirts or making signs or coming up with all sorts of creative ways to get our attention; “Help me. Save me.” They were everywhere.”

Helicopter rescues

NEW ORLEANS – (Aug. 30, 2005) A Coast Guard HH-65C Dolphin helicopter conducts a fly over of New Orleans the day after Hurricane Katrina made land fall on the Gulf Coast.

The helicopter from Air Station Corpus Christi participated in rescues in New Orleans and was responsible for saving many lives during and after Hurricane Katrina.

He refused to go check on his house

ATC Mobile was now running 24/7. In the mess hall, Callahan hung up “thank you” signs sent by school children, to help keep up members’ morale.

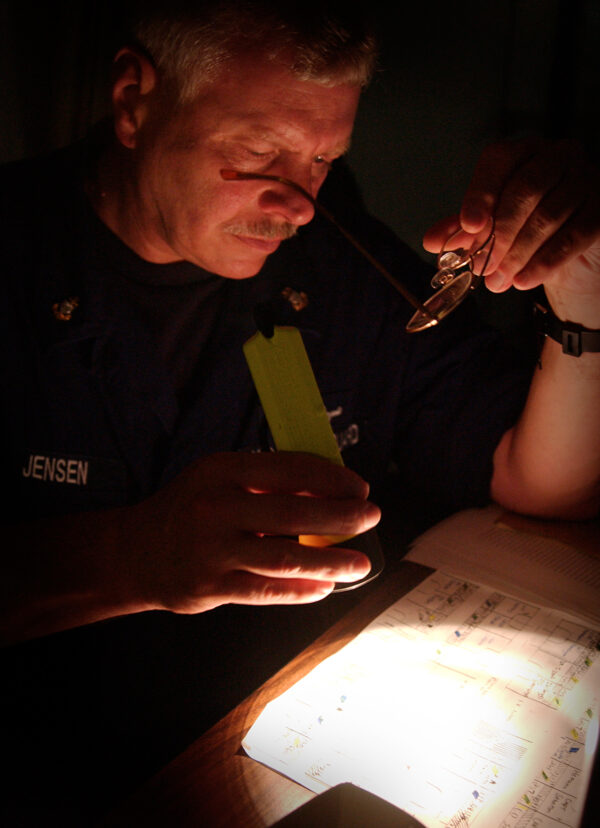

Chief Petty Officer Garth D. Jensen was in charge of running the galley situation, which was now feeding people around the clock.

“For the first time in the history of this place we had a MIDRATS (midnight rations), which I hadn’t done since I was on ships,” said CAPT Callahan. “Chief Jensen knew early on that he had lost his home, which was down on the Dog River. Yet he just refused to leave ATC Mobile to go look at his house. He just said, ‘Hey, we have an operation going on here and we’ve got to feed people around the clock so we’re going to do it.’”

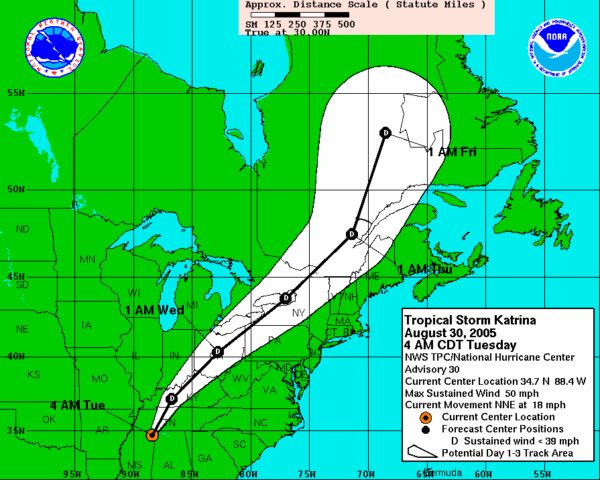

Wednesday, Aug. 31

-

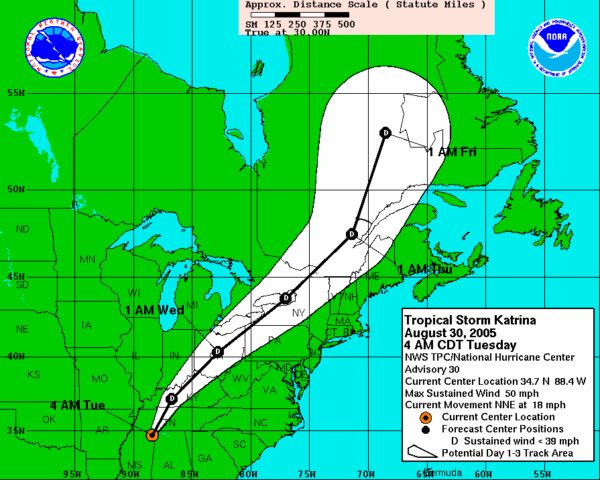

By 11 a.m. Katrina is downgraded to a tropical depression.

-

Water stops rising in New Orleans.

-

At 10 p.m., 85% of the city is underwater. The average home is under 9 feet of water.

-

Evacuations begin at the Superdome, which has been assessed as uninhabitable

-

Survivors seek shelter at the Ernest N. Morial Memorial Convention Center, which didn’t have food or water because it wasn’t a designated shelter.

On Wednesday morning, Heartland District reported that the skies from the Mississippi River to Mobile “ARE ORANGE WITH COAST GUARD AERIAL OVERFLIGHTS ACTIVELY CONDUCTING SAR IN AFFECTED AREAS.”

By this time, the original five pilots from AIRSTA New Orleans had “bagged out,” meaning they had flown too many hours. XO Scott Kitchen sent LTJG Shay Williams to the Superdome, where the Army National Guard was running its own SAR operation. Kitchen knew that his junior officer’s prior Army experience would make him a solid liaison, improving coordination between the two efforts.

“I told him I wanted to keep flying,” Williams said during a recent conversation. “He was like, Nope, you’re going to the Superdome. So I went over and set up an airlift.”

Right beside the massive Superdome building was a helipad and a trailer – Williams described it as a “shack” – that had become the National Guard’s Eagle Base.

“We cut down telephone poles so more helicopters could come in and land,” Williams said. “We spray painted frequencies on the [flight] deck so pilots would know how to talk to us. I was the only officer aviator there. Every other aviator was flying.”

Williams established some critical standard operating procedures, or SOPs, at Eagle Base. Every helicopter had to arrive with food and water to help feed the 20,000 people in the dome. When leaving, they had to take as many survivors as they could carry to safety in Baton Rouge. Those first two days, Williams said, they got 1,900 people out.

The Coast Guard’s boat forces and air crews all brought survivors to high and dry drop-offs, dubbed “Lilly Pads,” which initially included the I-10 Cloverleaf, the Convention Center, the University of New Orleans and the Superdome.

If we touch you, we own you.

But they soon discovered that no other agency was following through to get people from the Lilly Pads to more secure locations. Air crews saw people they had rescued yesterday were still there, standing in the baking sun and high humidity with little or no water or food.

“Frankly, I was very concerned about us taking people off roofs of houses where they were in immediate danger and putting them in places of relative safety and finding out there were staying there for longer than I anticipated that they would,” said Rear Adm. Duncan. “So we did two things. We ended up purchasing water in bulk. The first day we purchased 60 pallets of water – that’s about 70,000 little bottles of water. And I said, ‘If we touch you, we own you’. . .If we know we put you someplace we’re going to come back and check on you. We’re going to bring food. We’re going to bring water.”

Coast Guard officers used their unit credit cards to buy bottles of water in Clearwater, and flew them in a Coast Guard C-130 to New Orleans. Just as Williams was doing at the Superdome, ATC Mobile set up their own SOPs. “Every helicopter that took off after Wednesday took off with food and water,” Callahan said, “and the first order of business was drop off your food and water and then start picking people up.”

Sometimes, there was simply no way to help. This excerpt is taken from Capt. Bruce Jones’ after-action report:

“AIRSTA New Orleans is still getting calls from Baptist Memorial Hospital, where we’d rescued neonatal infants the previous evening. Water is rising. One generator is already out, and another about to go. They had few working phones, and little food or water. There were many critical patients. When our H60s arrived at the hospital’s helipad, they get waved off. The hospital then calls back to LTJG Decker, asking when the helos would arrive; there was a lot of internal confusion in the hospital. LTJGs Decker and Hall remained on cell phones with both the floor nurse and the helipad crew until evacs finally completed by three separate H60Js over a three-hour period. Hospital evacuation coordination continues to be a major lift for the next several days. Airsta NOLA, Sector IMT, Task Force Eagle, Acadiana Medical all partner together to accomplish the missions. Sometimes, there is simply no way to help. Rescue swimmer Chris Monville was dropped off at one hospice, where he found only one manager tending to 20 to 30 people. The patients’ medical condition was too severe to subject them to a hoist, and the crew had to leave them there. Very upsetting to crew and especially the rescue swimmer.”

Thursday, Sept. 1

-

Coast Guard helicopters have now made 4,468 rooftop rescues

-

Conditions at the Superdome and Convention Center continue to deteriorate.

By Thursday, LTJG Williams was “off the bag,” and able to fly again. He flew five or six hours of rescue ops, then got dropped off back at the Superdome.

“There were terrible things going on in the Superdome,” he told us. “There were dead bodies floating everywhere. It was bad.”

As the National Guard troops kept survivors from overtaking the SAR trailer, Williams suddenly found himself in a unique position. “I was the only one who had been flying, and I knew what was going on in the city. Anytime Adm. Duncan got asked a question by Ray Nagin, the city’s mayor, I would write the answer on a piece of paper and slip it to the admiral. Because I knew where there was water in the city, what areas had been cleared, and what hadn’t.”

All the while, he was directing SAR operations.

“The AIRSTA was too far and the radio wasn’t strong enough to manage operations,” he recalled. “So we were getting rescue requests that came into the shack next to the Superdome. I would run out to the helo pad and give them the lat/longs on a slip of paper.”

Shots fired at Tulane Hospital

LTJG Williams took a call from the manager at Tulane Hospital, which couldn’t evacuate any patients because someone was shooting at the helipad.

“The manager of Tulane Hospital [was] reporting that he had 200+ patients needing evac and that someone was taking shots at his helipad. The hospital requested someone to secure the pad and then evacuate the patients… A half-dozen fully armed Air Force personnel approach LTJG Williams and ask how they can help. He briefs them and puts them on a helo to Tulane Hospital to find and neutralize the shooter.”

Capt. Bruce Jones

A similar process was unfolding at AIRSTA New Orleans, which by now was feeling like “ground zero of a battlefield,” as Capt. Jones described it.

Power kept going out at AIRSTA New Orleans, but when it was up, staff were fielding reports of survivors from D8 IMT, Sector IMT, Eagle Base, other aircraft, ATC Mobile and direct calls from survivors themselves. Requests were tracked on flip charts hung on the wall. Tasking was passed on little slips of paper. Through all of this, command staff were tracking which sections of the city were in most urgent need at any given moment,and making instant decisions about where to deploy assets. The calls for rescue never slowed down – nor did Coast Guard members.

“We had folks coming back from eight hours of flying, utterly exhausted, sucking down bottle of Pedialite to keep from passing out, and then yet somehow a few hours later those folks were out turning aircraft around,” said Jones. “They were working. They were offloading pallets of food and water. After they got some sleep they were flying again.”

Although he’d never seen Coasties more beat up and tired, it was also the highest morale he’d ever experienced. “Every air station in the Coast Guard had people in the theater and every one of them was walking through my hangar deck.”

This was their fourth day of round-the-clock flight operations. “Our crews were extraordinarily successful, but also very stressed and on the edge. I was very concerned about the potential for a serious mishap,” Jones said. “My Ops [Operations Chief] and XO found a stopping point where most crews were on deck, and we held a one-hour safety standdown.”

Jones shared a general situation update, talking about all the hazards and the need to keep focused on safe operations no matter what. “I spoke to the crew about my pride in their extraordinary performance and thanked everyone for their magnificent efforts. XO and Ops also spoke at length. Then back to flight ops.”

Jones made sure there were still two H–60Js flying during the standdown, so there wouldn’t be any gap in SAR coverage.

"God bless all of you, and thank you for being here."

CAPT Bruce Jones holds an inspirational safety stand-down at Air Station New Orleans on Sept. 6, 2005.

Keeping people fed

About 200 miles north in Alexandria, Sector New Orleans was just as busy managing logistics for the entire Coast Guard operation.

Mrs. Leah Paskewich, felt intimidated walking around on her first day at her husband’s alternate command post. In one of the big conference rooms, she found five other spouses and significant others: Adam Wilkes; Shelley Ford; Leann Stump; Jeanie Muller and Bill Polk.

“We created an instant bond, and they told me that the command post had been set up but no food had been provided for – that that wasn’t part of the initial plan,” she said. “They had been working to procure food through the restaurants in the city, because they were working 18 hours a day and not able to leave.”

In the coming days, the families set up a massive public-private partnership that kept members fed throughout the response.