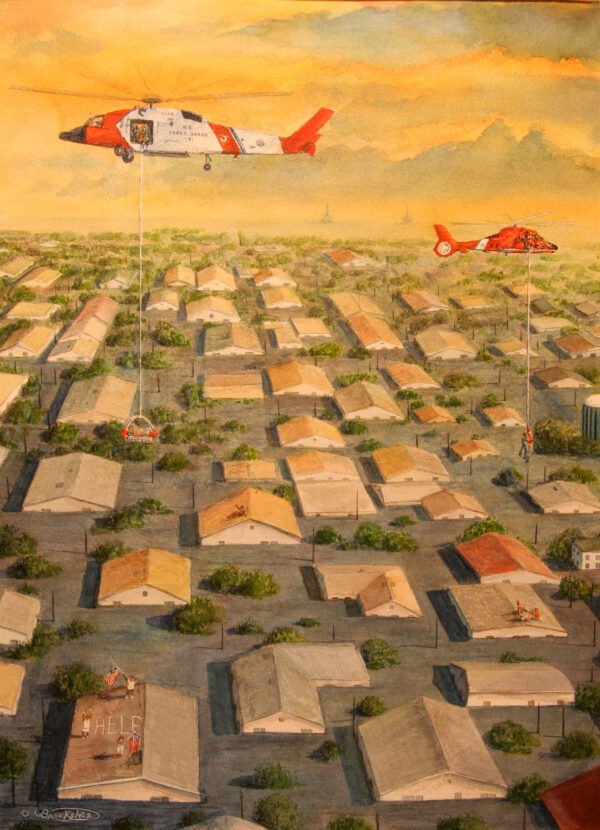

Although Coast Guard air crews back then did not train for urban search and rescue, they adapted quickly. Some had experience in flood relief conducting rescues after the 2001 Houston flood, while a number of personnel had trained to conduct cliff-side aerial hoists. Some pilots were Army veterans with experience flying in urban areas. But regardless of their background, all had to face the unique challenges of flying in a devastated urban environment.

The fact that all these aircraft, from all these agencies, completely avoided any major aerial mishaps has become known as the “Miracle of Katrina.”

Comms were limited, if at all, between pilots flying in close proximity. There were patchy comms between aircraft and their grown dispatch. And then there were telephone wires, debris, and even gunfire targeting rescue crews.

Capt. Bruce Jones, commanding officer of Air Station New Orleans, was constantly worried about a collision.

“The sky was dark with helicopters; definitely very, very congested,” he said. “And it was not possible to provide air traffic control to all of them because they were simply operating too close together.”

One HH-60J helicopter pilot, Cdr. Patrick Gorman, detailed the many difficulties the air crews faced in that environment.

“Wires are the worst thing that can happen to a helicopter. In fact, they are referred to as ‘helicopter catchers.’ The whole power grid was supposed to be dead, but the current doesn’t need to be running through the wires in order for it to ruin my day. I start sticking rotor blades in the wires and we’re done.”

Crews and survivors also had to contend with debris kicked up by helicopters’ rotor wash.

“You’d come up on an apartment building or something and there’d be enough damage done to it,” Gorman said, “that while you were hoisting someone on this roof you were really abusing the house over there – which might have a couple more people on it – shingles would be flying and insulation, hunks of wood.”

Gorman’s HH-60J “Jayhawk,” was an excellent SAR aircraft. Jayhawks were able to carry considerably more survivors and had the fuel to remain on scene much longer than the older HH-60Bs. Most of the helos, though, were the power-limited HH-65B “Dolphins” and Katrina pushed them to the limit of their performance. A few upgraded versions – designated HH-65Cs – flew during Katrina, and performed brilliantly.

But regardless of what helo they were flying, every pilot’s No. 1 job was keeping the rescue swimmers safe.

“We were threading them into some pretty tight places and down into this debris that we’re talking about,” Gorman said. “In some places we were hoisting down to a flat roof or a balcony, but a lot of times it was the pretty good peak of a roof and you’ve got to let enough slack out in the cable to let him maneuver – but not enough that he can fall off the roof.”

The ability to improvise on the spot was an important factor. “In general, improvisation is what Coast Guard aircrews do best,” said Lt. Iain McConnell, an HH-60 pilot from Air Station (AIRSTA) Clearwater. “We had things like hoisting to balconies, hoisting to rooftops. Or taking not just a flight mech and a swimmer but taking a flight mech, swimmer, and a basic airman in the back of the helicopter – so that while the flight mech and swimmer are busy hoisting people the basic airman can be the person in charge of strapping the survivors into their seats and managing the cabin.”

At first, McConnell said, his crew used basket hoists for most survivors. “But then the swimmers found that the quick-strop hoist technique was quicker, so that was another improvisation,” he said. “And the whole swinging like a pendulum to get a swimmer up onto a balcony underneath a roof, that’s definitely something you don’t practice to do. But those were fun.”

What amazed many of the flight crews was their ability to work together as a team even if they had never met the people they were flying with.

Capt. Jones noted the importance of the service’s standardized training. “And the fact that you can take a rescue swimmer from Savannah and stick him on a helicopter from Houston with a pilot from Detroit and a flight mech from San Francisco, and these guys have never met before and they can go out and fly for six hours and rescue 80 people and come back without a scratch on the helicopter. There is no other agency that can do that.”

A miracle indeed.

Editor’s Note: This package was developed based on an article originally written by Mr. Scott Price, the Coast Guard’s former historian. This history is dedicated to those responders’ devotion to duty, courage, humanity, and most of all their selflessness.