To the officers of the Greenland Patrol vessels: This is your command. Your first command. Your first great chance. It is hard, responsible, vital duty. War duty. Don’t fail your country or your ship or me.

RDML Edward Smith (USCG), Commander Task Force 24.8 (“Greenland Patrol”), 1944

Throughout much of history, Greenland has remained a forgotten land. It’s nearly one million square miles of land mass are covered with hundreds of feet of impenetrable ice. By 1940, it was sparsely populated with only 20,000 residents who lived in coastal villages only accessible by water.

At the time, world powers understood the importance of Greenland, including military supply lines from the United States, vital weather forecasts and mineral deposits required to produce war material. Before the war, Coast Guard cutters such as the Northland and Comanche had deployed for exploratory cruises in Greenland’s waters. On April 9, 1941, Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Danish Ambassador Henrik de Kauffmann signed an agreement that made Greenland a protectorate of the U.S., which extended the American Neutrality Zone eastward to a line located between Greenland and Iceland.

On May 6, 1941, Coast Guard operations came under the U.S. Navy, and, in October, the Coast Guard’s Greenland operations became Task Force 24.8, or the “Greenland Patrol,” under Coast Guard Cmdr. Edward Smith. The first Coast Guard missions included protecting Greenland and its citizenry; identifying locations for airbases and military facilities; charting coastal waters; transporting officials, personnel, and equipment to Greenland; search and rescue services; and protecting a cryolite mine vital to produce aluminum. According to naval historian, Rear Admiral Samuel Elliott Morison, the Chief of Naval Operations ordered the Coast Guard to “Do a little of everything—the Coast Guard is good at that.”

More than any other U.S. military service, the Coast Guard was uniquely qualified to oversee Greenland operations. After the 1867 acquisition of Alaska, revenue cutters regularly patrolled above the Arctic Circle. The Coast Guard’s Arctic operations grew as America’s strategic and commercial interests spread into icebound regions and its cutters evolved from vulnerable wooden sailing vessels to powerful steel steamships. However, the Greenland Patrol was the first and only time in Coast Guard history that the service oversaw an entire theater of operations.

Coast Guard engagement with Greenland dates back over 110 years to April 14, 1912. On that day, Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Titanic struck an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic resulting in the loss of 1,500 lives and the birth of a new Coast Guard mission. As a result, the United States agreed to patrol areas where icebergs posed a risk. The Revenue Cutter Service assumed the duty, and, in March 1913, Cutter Seneca initiated the Coast Guard’s International Ice Patrol, which persists to this day.

By the early 1920s, the Coast Guard began oceanographic research for the Ice Patrol. From 1923 to 1931, Lt. Edward Smith headed a unit at Harvard University providing iceberg data to the Ice Patrol. Smith developed a method for forecasting the annual berg numbers drifting south from Greenland. For his iceberg research, Smith became the first Coast Guard officer awarded a Ph.D., was recognized as the world’s iceberg expert, and became known as “Iceberg” Smith.

In the summer of 1928, Iceberg Smith commanded the cutter Marion on an expedition to Baffin Bay. Within two months, the expedition had covered over 8,000 miles and made thousands of recordings at 200 observation stations. The Marion Expedition was the largest oceanographic expedition ever made by the U.S. up to that time and the Coast Guard’s largest ever. Later, as commander of the Greenland Patrol, Smith would climb rapidly from commander to captain and then rear admiral and was one of only two Coast Guard recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal during World War II.

During the war, the Coast Guard had to fight two enemies. One was weather conditions of ice, snow, white-out visibility, temperatures down to negative 100 degrees, hurricane force winds up to 170 mph, and horrendous seas that hovered around zero and coated ships with tons of dangerous ice. As one Greenland Coast Guard skipper stated about the conditions his crew faced:

“I saw them hang on with one hand and break ice with the other, 20 out of 24 hours, in a 65-mph gale, with the ship on her beam ends, and the temperature at 5 degrees below zero. Cold, hungry, tired, and sleepy. . ..”

The Coast Guard’s second enemy was the German military. This enemy lurked under water, in the air and on land. U-boats patrolled convoy routes and long-range aircraft patrolled the skies. German ships supplied enemy weather stations on Greenland’s northeast coast that provided the Nazis accurate reports on weather days before it arrived in Europe. As commander of the Greenland Patrol, Smith established the Greenland Sledge Patrol. Based on dog sleds and manned by Danes and Innuits, the Sledge Patrol located these German stations. Considered a Special Forces unit by today’s standards, the Sledge Patrol continues to operate in the forbidding northeast Greenland area.

In the mid-1930s, the service had begun building tugs and cutters to break ice. Early on, the Greenland Patrol fleet was a small motley collection of these vessels. Others included the old wooden cutter Bear, wooden schooner Bowdoin, and ten hearty New England fishing trawlers. But, by war’s end, the Greenland Patrol boasted a fleet of more than 50 ice capable vessels.

Before the war, Greenland’s aids to navigation (ATON) included one lighthouse, rock pile markers on shore and posts to hang lamps at night. With wartime shipping increasing in Greenland’s waters, the Coast Guard began marking navigable waters. Three ATON working parties were put ashore for two years to set up range lights, shore markers and radio beacons at 50 sites. The Greenland Patrol fleet included three 180-foot buoy tenders capable of marking channels and carrying cargo to remote settlements along the coast. In early 1943, the Coast Guard also built a Long-Range Navigation station (LORAN) in southwest Greenland as part of a worldwide long-range radio navigation network called LORAN.

During its 20-year career, Coast Guard cutter Northland became the most important vessel in the Arctic. Designed for Alaska’s Bering Sea Patrol, Northland served as the Greenland Patrol’s flagship and, in 1941, it seized the first enemy vessel by U.S. forces. Northland also became famous for her officers and men. Besides Iceberg Smith, Northland captains Carl von Paulsen and Charles Thomas went on to become historic figures in ice operations. Northland aviators, Lt. John Pritchard and Radioman Ben Bottoms gave their lives saving downed aviators from the icecap. They remain the service’s last MIAs. On Northland, Motor Machinist Oliver Henry, broke the color barrier for enlisted Blacks and navigation officer, Lt. Carlton Skinner, later led in the desegregation of U.S. sea services.

World War II would mark a shift in the Coast Guard’s icebreaking mission from light ice to thick ice in Polar Regions such as Greenland. In 1943, the Coast Guard began commissioning “Wind”-Class icebreakers for Arctic icebreaking. Three of them served in Greenland. These capable heavily armed ships would become the backbone of America’s Cold War icebreaking fleet.

Coast Guard cutters also escorted convoys to and from Greenland. These dangerous convoys steamed through the ice-cold U-boat infested waters between Greenland and ports in Canada and the northeast U.S. Convoy ships destined for Greenland carried troops, supplies, and construction equipment for building military airfields, buildings, and shore installations. At least one cutter was lost escorting these convoys.

One of the service’s core missions is search and rescue, even in wartime. With Greenland waters hovering around freezing, Coast Guard units were challenged to save anyone from the water. With a Semper Paratus spirit and survival suits, Greenland cutters devised a tethered rescue swimmer method that saved victims without endangering the rescuers. In all, Greenland cutters saved hundreds of lives from torpedoed vessels, such as Army Transports Cherokee, Dorchester, and Nevada. Credited with saving 130 men from the Dorchester, Cutter Escanaba was later lost to an explosion with nearly all hands.

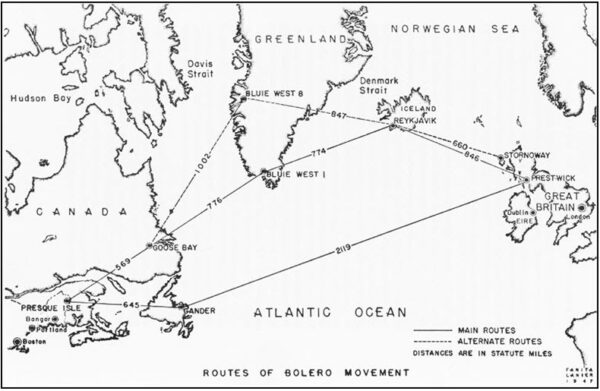

The earliest aircraft to fly Greenland’s skies were Coast Guard cutter-based amphibian aircraft called “Ducks.” The Allies had to fly military aircraft from the U.S. to the U.K., so in January 1942 the Army completed Greenland’s first airbase designated “Bluie West One,” headquarters for the Army Air Corps and Coast Guard. Three more Army airfields were built in Greenland. Bluie West One hosted 12 Coast Guard PBY “Catalina” amphibious aircraft that searched for U-boats and enemy outposts, escorted convoys, delivered mail, tracked icebergs, and directed rescue parties to downed aircraft. On one occasion, a PBY spotted a crippled Royal Navy ship, whose crew had been adrift for over a month and directed a cutter to save the men. By the end of 1944, the PBYs had flown a total of 650,000 miles over an area of three million square miles of land and sea.

Coast Guard assets lost in the Greenland theater included the Trawler Natsek, Cutter Escanaba, weather ship Muskeget, and Northland’s Grumman J2F-4 “Duck.” In Greenland’s waters, the service lost over 250 Coast Guardsmen, due mainly to lost cutters and men lost on transport Dorchester. The heroes who died included Coast Guard cutter namesakes Benjamin Bottoms, Charles David, Warren Deyampert, and Forrest Rednour. Aboard the Northland and later cutters, cutter namesake Oliver Henry broke color barriers and trailblazed military desegregation.

The Coast Guard has been engaged in the Greenland area since the early 20th century. World War II saw the greatest Coast Guard involvement in Greenland, with the service overseeing military land, sea, and air forces for this strategic place. For Army airfields that sent 10,000 aircraft to Europe, the Coast Guard provided supplies, personnel, equipment, and SAR services. Meanwhile, the Coast Guard protected Greenland’s citizens; charted navigable waters; supported construction of roads and buildings; and prevented enemy incursions.

After the war, the Greenland Patrol was decommissioned, but the Coast Guard still served. The Ice Patrol was re-established, and the service established a LORAN station at Cape Atholl. The service also performed oceanographic research in Greenland waters and operated icebreakers for Cold War military bases, such as the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line. Today, the Coast Guard remains engaged with Greenland through international exercises, such as “Argus” and “Nanook”; occasional icebreaking duties; transits of the Northwest Passage; and the annual International Ice Patrol.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The museum will tell the harrowing story of the Greenland Patrol, along with the many varied duties of the Coast Guard during World War II, in the World War II exhibit in Deck 3’s Defenders of our Nation Wing.