In 1884, over 140 years ago, the S.S. City of Columbus rescue became the most honored response effort in the history of the Revenue Cutter Service and the first time in Coast Guard history that a cutter worked together with shoreside boat crews to save victims from a shipwreck. However, the story’s history began 50 years earlier with the establishment of the Revenue Cutter Service’s “winter cruising” mission.

As with many other Coast Guard missions, the service’s winter cruising mission was written in blood. In the 1790s and early 1800s, cutters in northern waters were typically laid up during the winter months. However, in the 1820s and early 1830s, immigrants from Western Europe began sailing for America in search of a better life. These immigrants took passage year-round, including stormy winter months, and many of their passenger ships foundered at sea or went ashore as they neared the coast.

As the number of disasters climbed, the American public was horrified by mounting body counts. Awareness of the growing loss of life on American shores and at sea peaked in 1837. In January of that year, the barque Mexico came ashore during an icy storm near New York with the loss of over 100 passengers. On January 9, the Adams Sentinel Newspaper reported:

When they perceived that no further help came from the land, their piercing shrieks were distinctly heard, at a considerable distance, and continued through the night, until they one by one perished. The next morning, the bodies of many of the unhappy creatures were seen lashed to different parts of the wreck, embedded in ice. None, it is believed, were drowned, but all frozen to death. Of the 104 passengers, two-thirds were women and children.

After the Mexico tragedy, Congress tasked the Revenue Cutter Service with aiding ships in distress, especially during the winter. On Dec. 22, 1837, it passed an act for winter cruising requiring cutters to “cruise upon the coast, in the severe portion of the season, and to afford such aid to distressed navigators as their circumstance and necessities may require; and such public vessels shall go to sea prepared fully to render such assistance.” By the mid-1880s, winter cruising had been a seasonal mission of the Revenue Cutter Service for decades.

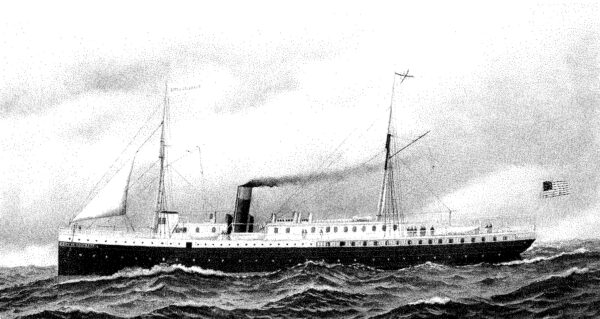

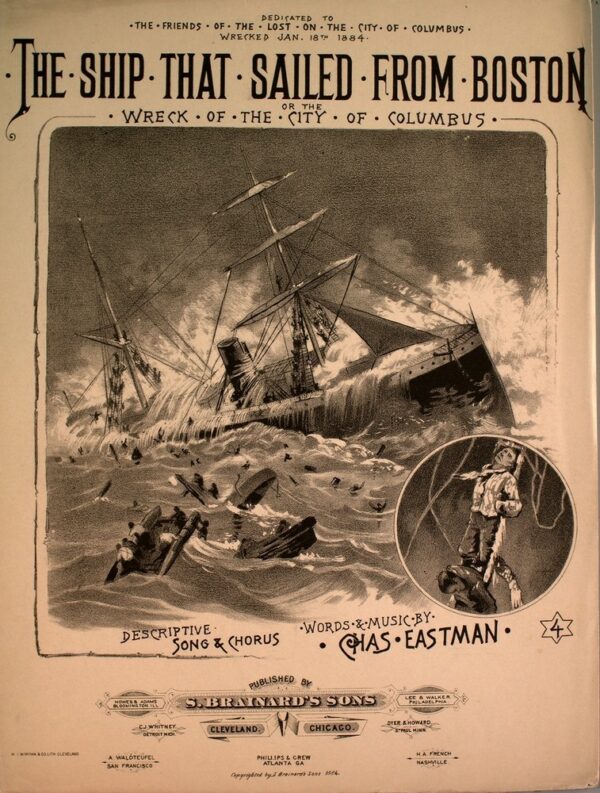

On Thursday, Jan. 17, 1884, the 275-foot iron passenger liner City of Columbus got underway from Boston destined for Savannah with 45 crew members and 87 passengers. The next morning at around 4 a.m., she was steaming through a freezing gale, when she ran aground on Devil’s Bridge Ledge off Gay Head, Martha’s Vineyard. As the iron vessel settled in the shallows, a handful of crew and passengers embarked two lifeboats while others climbed the vessel’s masts to escape the bone-chilling waters. The rest of the passengers and crew were swept into the water and drowned or froze to death within 20 minutes.

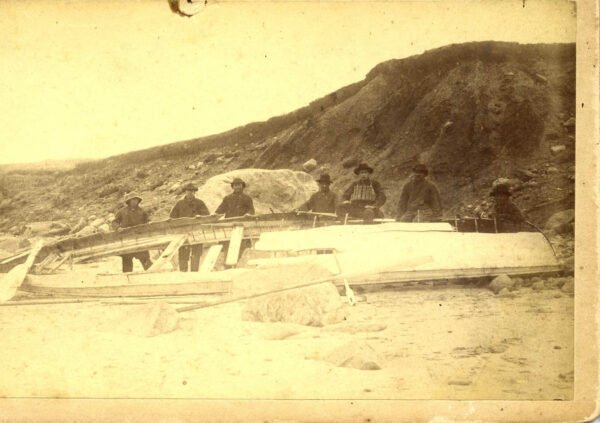

Later that morning, Aquinnah Wampanoag volunteers assembled on the beach at Gay Head to man rescue boats in bitterly cold temperatures and heavy seas. Under the command of Gay Head Lighthouse keeper Horatio Pease, these Native American heroes manned two Massachusetts Humane Society boats, a lifeboat and a larger surfboat.

After launching into the towering waves, the lifeboat was crushed against the rocks and lost. The boat crew were soaked and stunned but they survived. Meanwhile, their brethren lifesavers launched the surfboat, which capsized in the heavy surf. Despite the bitter cold, these waterlogged rescuers drifted ashore and tried again to reach the survivors hanging from the masts of the submerged steamer. Of these dramatic events, Aquinnah Wampanoag lifesaver Samuel Anthony later recalled, “We were on our trip to save lives or lose our own in trying.” The intrepid Native American crew managed to retrieve seven survivors and rowed for shore. Again, the surfboat overturned, however, the crew and survivors washed ashore safely and survived. Risking their own lives, the Wampanoag rescuers saved seven souls with another five survivors washing ashore in the passenger ship’s damaged lifeboats.

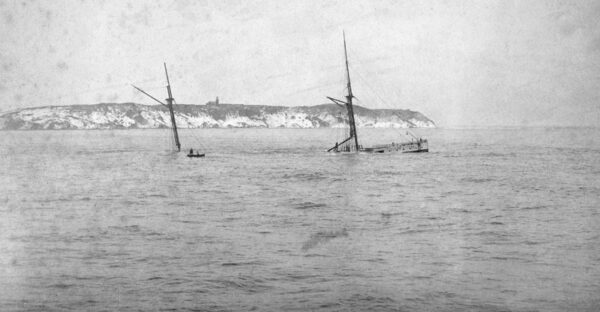

Meanwhile, Revenue Cutter Dexter was performing winter cruising patrols out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Her crew spotted the ill-fated City of Columbus around noon that day and stood by to assist. Dexter deployed a lifeboat under the command of young cutter officer Lieutenant John Rhodes. His lifeboat went to the aid of several people hanging from the City of Columbus’s masts, which were still standing above the heavy seas. Thirteen men jumped from the rigging and were promptly picked up by the boat crew, however, two more had passed out and were frozen to the masts. Lt. Rhodes tied a line around his waist and jumped into the water but was injured by floating wreckage. He returned to the masts in a lifeboat and climbed the icy rigging. By the time Rhodes reached the men, they had frozen to death, so he cut down the bodies and brought them back to the Dexter. Rhodes and his boat crew had saved the lives of 17 men freezing in the ship’s rigging.

For their heroic lifesaving efforts, Dexter’s crew members were showered with honors, awards and recognition. A joint resolution of Congress thanked them for their bravery and Treasury Secretary Charles Folger ordered praise for the crew be read aloud on board every revenue cutter. The Massachusetts Humane Society presented a gold medal to Lieutenant Rhodes and silver medals to Dexter’s captain and another officer. Rhodes also received a solid gold Maltese Cross from the German American community of Wilmington, North Carolina. With all his medals and awards, Rhodes became the most decorated individual in the history of the Revenue Cutter Service.

The Aquinnah Wampanoag men also became nationally famous. Members of the all-volunteer force became the focus of dramatic press coverage and received high praise, medals and cash awards from the Massachusetts Humane Society. In reporting the story, the press wrote that the Native American men and their wives, who aided the victims ashore, were “deserving of all praise and the fund for their benefit and encouragement should assume large proportions. Without any expectations of reward, they periled their lives for others.”

After all the living and the dead had been retrieved from the wreck of the City of Columbus, the ship was left alone in the seas, her icy rigging glistening in the freezing January sun. Of the City of Columbus’s 132 passengers and crew, only 17 crew members and 12 passengers survived. The remaining 103 souls died of exposure or drowned in the stormy seas. Cutter Dexter later delivered the survivors to New Bedford, before they were sent back to Boston. The once proud passenger liner would later be salvaged for parts and machinery.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The Coast Guard has a long heritage of incredible rescues like this one and visitors will get to learn the history of lifesaving from the early 1800s to the modern day on Deck 2 of the National Coast Guard Museum.