In 1815, the lighthouse keeper at Gay Head Light, Martha’s Vineyard, hired members of the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe as assistants. The keeper recommended these men as the best workers available to support lighthouse operations. Since then, Native Americans from a variety of tribal nations have participated in the Coast Guard and its predecessor services representing the second earliest minority group to serve in the Coast Guard.

The first Native Americans to participate in Coast Guard predecessor services typically came from coastal tribes whose members were expert watermen. These tribes included the Wampanoag in Massachusetts, Mohegan in Connecticut, Shinnecock in Long Island, Algonquian in North Carolina, Ojibwe in the Great Lakes, and the Makah and Quileute tribes in Washington State. These Native American men served at shore bases in the U.S. Lighthouse service and the U.S. Life-Saving service. Later, members of various Plains Indian tribes served as well as Native Alaskans.

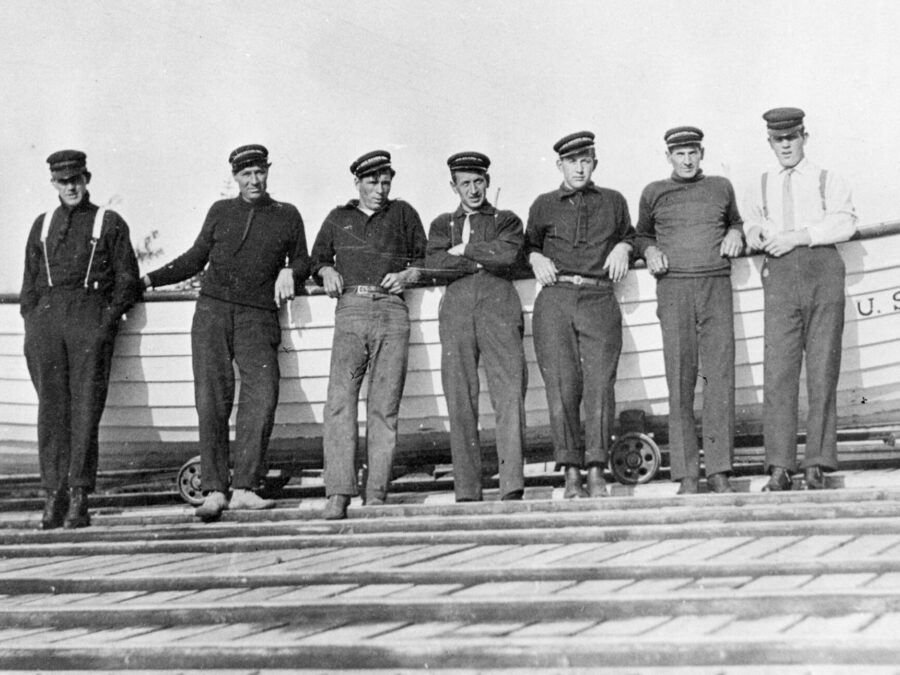

In 1877, before Washington Territory received statehood, a white keeper and an entirely Native American crew began operating the Neah Bay Life-saving Service Station. The Neah Bay crew included Makah and Quileute surfmen, such as As-chik-abik, Que-dessa, Tsos-et-oos, and Tsul-ab-oos. With the exception of Native American scouts employed by the U.S. Army, this station was the earliest Native American unit in federal service. Ironically, the Neah Bay Station was established a year after the defeat of George Custer’s cavalry by Sioux warriors at the Little Big Horn. In 1880, the U.S. Life-Saving service also appointed an all-black crew and keeper to the Pea Island Life-Saving Station. It is believed many of these African American surfmen had Algonquian ancestry.

In 1884, the coastal steamship City of Columbus ran aground at Gay head, Martha’s Vineyard. Led by Gay Head Lighthouse’s white keeper, Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal members served as volunteer lifesavers with the Massachusetts Humane Society. These Native American lifesavers braved stormy seas to launch a surfboat into the waves. In their first attempt, the surfboat capsized, but the crew returned to shore safely. The surfmen tried again and reached the last survivors hanging from the masts of the submerged steamer. On the return trip, the crowded surfboat capsized again, however, the crew and survivors got ashore safely. The Aquinnah Wampanoag rescuers were honored by the Massachusetts Humane Society with high praise, medals and cash awards.

In 1892, City of Columbus Aquinnah Wampanoag lifesaver Leonard Vanderhoop was appointed Assistant Keeper of Gay Head Lighthouse becoming the first Native American to serve as deputy supervisor of a federal installation. In 1895, the U.S. Life-Saving service established the Gay Head Lifesaving Station on Martha’s Vineyard Island with a white keeper and a crew of Aquinnah Wampanoag surfmen, including two of the lifesavers from the 1884 City of Columbus rescue.

Native American Coast Guardsmen have also served with distinction in time of war. In 1918, during World War I, the Native American community of Gay Head was honored by the State of Massachusetts for sending more men to war by percentage of the population than any other town in New England. Among the Aquinnah Wampanoag men who served were six current or former Coast Guardsmen. This number included Samuel Anthony, who had served in the 1884 City of Columbus rescue and was one of the original surfmen of the Gay Head Lifesaving Station.

In 1918, Francis Leroy Wilkes lost his life when a U-Boat sank Cutter Tampa. He was African American and at least one-quarter Wampanoag Indian. He posthumously received the Purple Heart Medal and Wilkes Square in Nantucket was dedicated in his honor shortly after the war. He was the first Coast Guardsman with Native American ancestry awarded a military medal for combat heroism. Carlton West, another Wampanoag citizen of Nantucket, enlisted in March 1918. He served in in World War I on board Cutter Gresham and, in World War II, he volunteered to serve in the Coast Guard on the home front.

In 1919, Aquinnah Wamapnoag Charles W. Vanderhoop was appointed Principal Keeper of Sankaty Head Lighthouse on Nantucket Island. He was the first Native American appointed to oversee a federal installation. In 1920, he and Aquinnah Wampanoag Max Attaquin were appointed Gay Head Lighthouse’s Principal Keeper and Assistant Keeper, respectively. Over the next 13 years, they provided tours for approximately 300,000 visitors, including men, women and children and celebrities such as President Calvin Coolidge. In 1985, Aquinnah Wampanoag Charles W. Vanderhoop, Jr., son of Charles W. Vanderhoop, became Assistant Keeper of Gay Head Light and made history as the first Native American father and son lighthouse keepers in U.S. history.

In 1921, Mohegan Tribe member Harold A. Tantaquidgeon enlisted in the Coast Guard on board the cable-laying vessel Pequot. In 1927, Tantaquidgeon advanced to Chief Boatswain’s Mate becoming the first Native American chief petty officer in the service. That same year, he became officer-in-charge of the 75-foot cutter, CG-289, and the first Native American to command a Coast Guard cutter. Tantaquidgeon left the service in 1930, after commanding CG-289 in Prohibition law enforcement operations for three years and serving nine years overall. He returned to the Mohegan Tribe in Connecticut where he later became Chief Tantaquidgeon, head of the Mohegan Tribe.

In 1921, Howard J. Kischassey, a full-blooded Chippewa tribal member of the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, transferred from the Navy to start an enlisted career in the Coast Guard. By 1938, Kischassey, had become a chief radioman, served as officer-in-charge of the Coast Guard station at Dam Neck, Virginia, and oversaw a crew of six radiomen, three surfmen and a cook. In March 1942, Kischassey, promoted to warrant radio electrician. He was the Coast Guard’s second Native American chief petty officer and its first Native American warrant officer. In 1943, he was promoted to lieutenant junior grade (temporary) and lieutenant in 1944. In March 1947, Kischassey retired with the permanent rank of lieutenant. He was the first Native American to serve as a warrant officer, lieutenant junior grade and lieutenant.

During World War II, George “White Bear” Drapeaux, of the Sioux Nation, was the first Native American Coast Guardsman to participate in World War II combat operations. In early 1942, he served as a gunner’s mate on board the Coast Guard-manned transport USS Wakefield. The Wakefield lost several crewmembers to Japanese bombers while evacuating civilians from Singapore before it fell to the enemy. Also in 1942, Pawnee tribal member Joseph R. Toahty operated a landing craft along with Medal of Honor recipient Douglas Munro during the Battle of Guadalcanal. He was the first Pawnee to serve in World War II and the first Native American to step foot in enemy-held territory during the war.

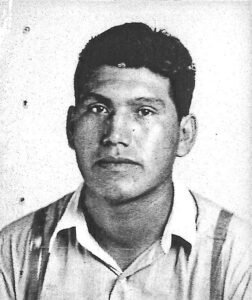

In 1943, Chickasaw citizen James J. Leftwich enlist at the age of 14. He was the youngest known enlistee in the history of the modern Coast Guard. At the age of 16, he suffered combat wounds in the Battle of Eniwetok Atoll becoming the youngest Coast Guardsman to receive wounds in combat and the Purple Heart Medal. In December 1954, Leftwich advanced to chief boatswain’s mate, becoming the third Native American known to make chief petty officer. In 1957, Leftwich was appointed an ensign, becoming the second known Native American officer in the Coast Guard and, in 1964, Leftwich retired as a lieutenant after a 20-year career, before reaching the age of 35.

World War II also saw the first Native American women serving in unform as members of the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, or SPARs. Motivated by patriotism, these Native American SPARs enlisted from several tribal groups. Six patriotic women from the Otoe-Missouria, Choctaw, Yuchi, and Cherokee tribal groups enlisted in Oklahoma, joining their state’s “Sooner Squadron.” While the media sensationalized their heritage by referencing popular culture stereotypes, they contributed to the U.S. victory by serving in yeoman and seaman ratings. Native Alaskan Seaman First Class Sophia Thadei served at Charleston. While on duty she suffered a life-threatening medical condition and died on the way to the hospital. She is considered the first female service member to die in the line of duty.

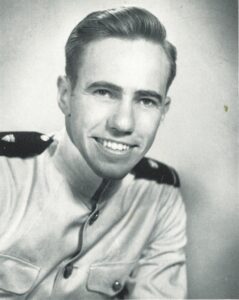

Minority men began entering the Academy’s four-year program late in the war. Native Americans led the way. Entering in 1944 and graduating in 1948, Mohegan tribe member Donald Chapman became the first Native American to graduate from the academy. He was also the first known minority graduate of the Academy. He later became the first Native American Coast Guardsman promoted to officer ranks of lieutenant commander and commander.

In 1959, Joseph Wicks, a member of the Sioux tribe, commissioned into the Coast Guard as a Lieutenant junior grade after a distinguished career in the merchant marine. He served in Vietnam as executive officer of the Coast Guard Cutter Mendota and received the Navy Commendation Medal and Presidential Unit Commendation for supporting Operation “Market Time” patrols and operations “SEALORDS” and “Silver Mace II.” In 1980, Wicks was promoted to captain, becoming the first Native American to achieve that officer’s rank.

In the past 30 years, Native American women have begun reaching higher levels in the officer and enlisted ranks. 1991, Mara Huling became first Coast Guard woman with Native American ancestry to graduate from the Coast Guard Academy and, in 1995, she became the first Coast Guard pilot with Native American ancestry. In 1995, the next female Academy cadets of Native American ancestry, Patricia Calhoun and Octavia Poole, graduated from the Coast Guard Academy. More recently, Native Alaskan Michelle Roberts became the first Native American woman to advance to command master chief.

Native Americans have been members of the Coast Guard and its predecessor services for well over 200 years. These Coast Guard men and women have served as officers and enlisted personnel in every branch of the service, and they have helped lead the way for all Coast Guard minorities. Like all other service members, they walk the long blue line, and their efforts have benefitted all who serve in the U.S. military, federal government, and the nation as a whole.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will have the opportunity to learn more about the important contributions of Native Americans across the service’s history throughout all three exhibit decks!