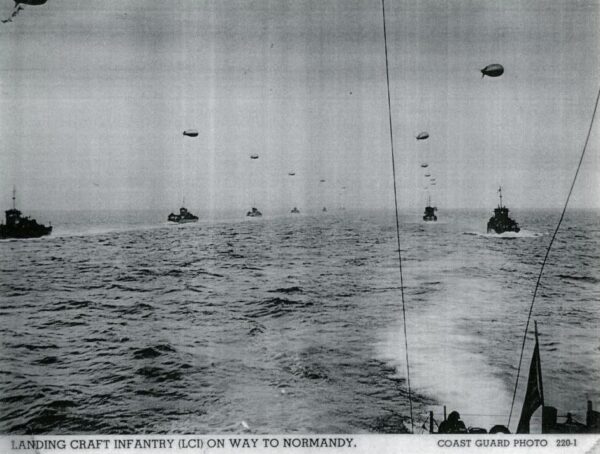

“Into the Jaws of Death”—Coast Guard landing craft at D-Day

From the Long Blue Line, by Scott T. Price, Chief Historian, U.S. Coast Guard

Breadcrumbs

Subpage Navigation

Among the many historical items kept by the Coast Guard Historian’s Office is a copy of one of the most reproduced photographs to come out of June 6, 1944—D-Day. The photograph was captured by Coast Guard Chief Photographer’s Mate Robert F. Sargent and entitled “Into the jaws of death.” Sargent, a veteran of the invasions of Sicily and Salerno, took the photo from his landing craft at sector “Easy Red” of Omaha Beach around 7:40 a.m. local time.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Chief Photographers Mate Robert F. Sargent.

Original caption: “Into the Jaws of Death: Down the ramp of a Coast Guard landing barge Yankee soldiers storm toward the beach-sweeping fire of Nazi defenders in the D-Day invasion of the French coast. Troops ahead may be seen lying flat under the deadly machinegun resistance of the Germans. Soon the Nazis were driven back under the overwhelming invasion forces thrown in from Coast Guard and Navy amphibious craft.”

Operation Neptune, the naval assault phase of Operation Overlord, was the largest single combat operation the Coast Guard has ever taken part in. During those initial days of the liberation of Western Europe, the service demonstrated its expertise, versatility, and value as a maritime service in several ways: combat operations; ship and small boat handling; loading and discharging cargo at sea and ashore; directing vessel traffic; and search and rescue operations—in most cases under enemy fire.

But the Coast Guard carried out another important mission—sending combat photographers and correspondents in with the troops. Thus, Sargent was at Normandy where he was able to capture the most famous invasion in modern history.

The Historian’s Office recently acquired a copy of the press release issued with the publication of Sargent’s photograph. Printed on brittle mimeograph paper, it has browned with age but is still legible. It was written by Coast Guard Combat Correspondent Thomas Winship who quotes Sargent extensively.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Combat Photographer S. Scott Wigle

This was one of the first Allied photographs taken on D-Day approved by censors and sent out over the wires that same day.

In it, Sargent details his experiences from that morning’s action and gives a firsthand glimpse through his eyes of what it was like to take troops into an enemy-held beach under fire. He also lists the crew of the landing craft transporting who took him and their Army passengers ashore safely at Omaha Beach.

The coxswain of the boat was William E. Harville of Petersburg, Virginia— it was his landing craft, and he was at the helm. The boat engineer, the crewman who kept the boat’s engine running smoothly, was Seaman 1st Class Anthony J. Helwich of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Seaman 1st Class Patsy J. Papandrea was the bowman — the crewman who operated the front bow ramp and is visible as the helmeted head in the right foreground of the photo. Sargent also mentions among their passengers was the “First Wave Commander Lieut. (j.g.) James V. Forrestal, USCGR,” of Beacon, New York.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Chief Photographers Mate Robert F. Sargent.

U.S. Army troops crouch behind the bulwarks of a landing craft as it nears Omaha Beach on D-Day.

The attack transport Samuel Chase, part of Task Group 124.3, arrived in the transport area 10 miles off Normandy’s shore and anchored on the morning of June 6 at 3:15. The ship began embarking troops at 5:30 a.m. The first waves got underway at 5:36 a.m. and the last wave launched a little after 6 a.m.

The trip was rough, according to Sargent and others, with many of the amphibious tanks swamping well off the beaches. He noted the soldiers aboard were all quiet and everyone was “cold and soaked to the skin” with waves breaking over the small vessel’s “square bow.” As they approached Omaha Beach, they could see the tide was slowly coming in but most of the obstacles the Germans had placed to prevent exactly what the Allies were attempting to do were still visible and in place.

Sargent goes on to describe seeing a disabled amphibious tank and another landing craft that broached along the beach just as they got ready to lower the bow ramp. German artillery bracketed their landing craft, but they managed to disembark all the troops in chest-deep water without taking any casualties and then deftly maneuvered back out to sea. Although they were unscathed, he described what happened in the landing craft close aboard their port side. The coxswain of that landing craft was Delba L. Nivens, a “sandy-haired, lanky sailor” from Amarillo, Texas. His crew consisted of boat engineer John Schell and bowman Leo Klebba.

According to an account given by Nivens, a German shell exploded a grenade being carried in the pocket of one of the soldiers in the landing craft, causing a fire on the port side forward. Of course, all aboard shifted to avoid the fire and as one can see, in the photo Sargent captured, the landing craft is leaning heavily. After disembarking the surviving troops and fixing their broken bow ramp, all while under fire, they managed to extinguish the fire and return safely to the Chase.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Chief Photographers Mate Robert F. Sargent

An American landing craft on fire off Omaha Beach, crewed by Delba L. Nivens, John Schell, and Leo Klebba.

In all, though, the Chase lost six landing crafts during D-Day, with four foundering near the beach, one impaled by a beach obstacle and another sunk by enemy gunfire. Sadly, they also lost one of their shipmates, Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class Harry L. Siebert Jr. who was killed-in-action. Siebert was one of 15 Coast Guardsmen who gave their lives at Normandy that day.

Credit: National Archives

Coast Guard Chief Photographer’s Mate Robert Sargent (left) shows Coast Guard Motor Machinist’s Mate Clyde Wilson a picture of the battle-blasted Coast Guard-manned LCI that Wilson served on D-Day. Both men were veterans of the invasions of Sicily, Italy, and Normandy.

The Coast Guard’s actions during Operation Overlord were exemplary on all counts. That their actions are remembered and recounted is due in part to the dedication of the Coast Guard combat correspondents and photographers who went into battle and captured those actions on film and in print.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors will have the opportunity to learn more about the numerous roles the Coast Guard filled during D-Day, from combat photography to search and rescue, in the WW2 exhibit on Deck 03 of the museum.