I know exactly what you are thinking, the three of us will probably die trying to save one guy, who will die also. Get in the boat; we have a job to do!

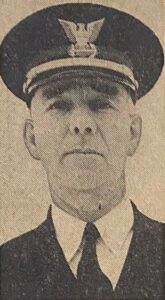

– Warrant Officer Altson J. Wilson, 1938 Hurricane

On that September morning in 1938, just before the storm’s arrival, there was a surround-all, eerie feeling, which seemed to permeate everything. The visible horizon had a purple and coppery cast to it and complete silence created an ominous feeling. Not a breath of air was stirring. No one was sure of what was approaching—the conversations were hushed and speculative about the silence and the threatening sky. Lake Ontario in New York was like a mirror—not a ripple.

All these unusual weather conditions that September morn had everyone guessing what was actually going to happen. It would turn out to be the mightiest storm ever to strike North America. The U.S. Weather Bureau was aware and tracking the huge disturbance, realizing what was happening and trying desperately to warn all of those in the storm’s path. Their warning task was difficult. The ocean waves generated by the storm that struck the New England coast were being recorded as earthquake tremors on seismographs in Canada.

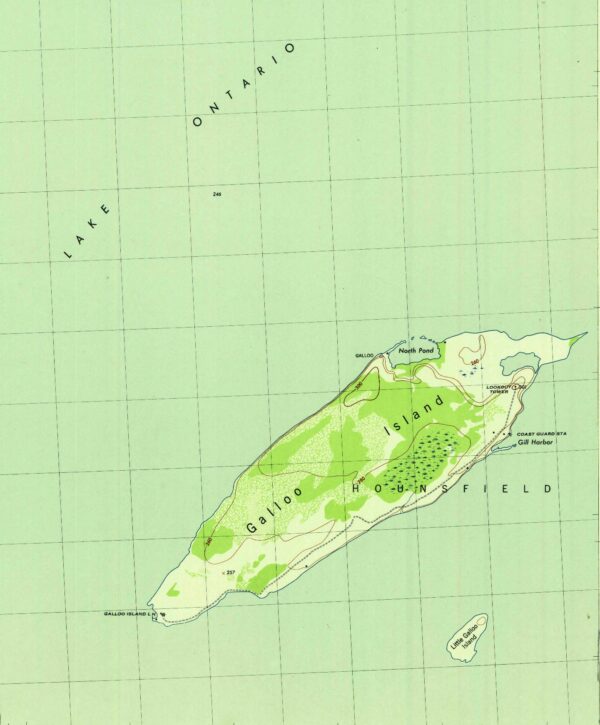

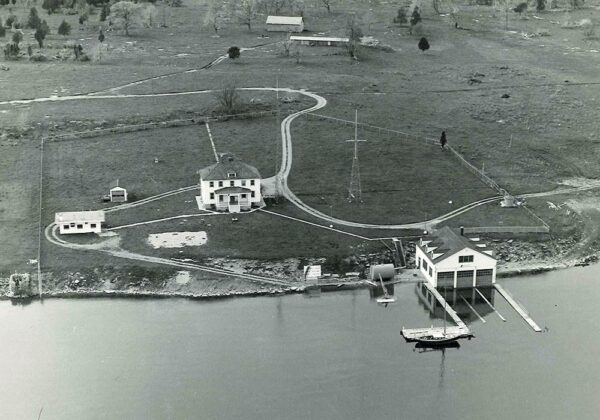

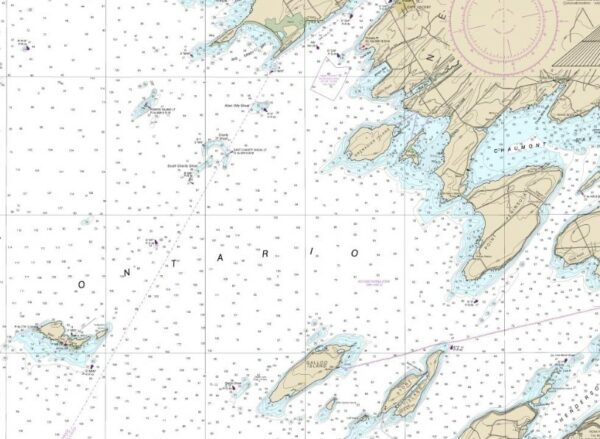

Located at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, Galloo Island was going to be within the western limits of this gigantic meteorological disaster. The new Coast Guard lifeboat station under construction on the east end of the island was in the path of the storm. There was still work to be done on the boathouse and the water system. The dredging of a navigable channel to Lake Ontario from Gill Harbor was nearly complete. This channel permitted deep draft power boats, such as the station’s 36-foot motor lifeboat, to travel to and from the small, protected waterway named Gill Harbor.

The crew of the barge dredging the channel was busily securing the dredge to shore in an attempt to keep it from breaking away when the storm hit. Large lines and cables were secured to suitable tree trunks. Two anchor steel cables were trapped in rock crevasses. The huge dredging bucket was placed as far as possible from the barge so it could act as an additional anchor. All seemed secure for the dredging barge as the storm approached.

In those days, most of the lifesaving stations, or lifeboat stations, had eight personnel. Each surfman was assigned a number between one and eight with the number one guy as the “captain” or “skipper.” In the case of Galloo Island Boat Station, it was Chief Warrant Officer Altson J. Wilson who ran the station with an iron hand.

Wilson was a great swimmer. He seemed totally relaxed above or below the surface. I had met him during a rescue when I was a child and he was a surfman. He was firing a Lyle gun to get a line to the SS McTear when it foundered on the rocks near our family farm. He was a friend of my mother’s and referred to her as a “physicist.” The first mate, Surfman #2, was the guy who ran most everything. That guy was Ralph Matteson. The station’s cook was Surfman #3. The rest of the crew were numbered according to seniority, and at that time I was Surfman #8.

Morning and evening colors observances were strictly enforced at the Galloo Island Lifeboat Station. The crew also sang patriotic songs before and after the morning colors ceremony. Each crewmember was allowed a day off every week if he could be spared. The surfmen ranked below #3 stood a continuous lookout watch and, after dark, made patrols every two hours to the Canadian side of the island to the north. The lookout watches were also two hours. The five men who stood the tower watches and patrols by boat or on foot were always sleep deprived.

Back to the hurricane of September 1938. The hurricane was the most powerful storm to strike the North American continent. This gigantic meteorological phenomenon would cover Galloo Island. The Weather Bureau was broadcasting expected wind velocities the day and night before the hurricane’s approximate time of arrival. The sky in the afternoon turned a bronze color. Darkness was falling fast. The copper-colored sky encompassed everything. It was very depressing.

The velocity of wind was increasing rapidly. Wilson headed outside, opening the main door which swung inward and then the heavy screen door which swung outward. The outer door was yanked out of his hand, blew off its hinges, and flew into the darkness. Wilson stepped back inside and leaned against the remaining door.

At the time, the lake water was surging four to six feet around the island. The dredging barge was straining violently against its tethers. Its faithful, one-man crew was gallantly stoking the boiler fires to keep the steam siphon going and pump the bilges of the barge. As we watched in horror, an extremely large and powerful wave smashed the dredging barge a mighty blow—the barge was free of its moorings and heading for the lake.

The barge struck beam on the reefs that form Gill Harbor, pausing a moment and then drifted on to Lake Ontario. Wilson witnessed the entire breakaway, turned to Matteson, and said “Mr. Matteson, is there anyone on the barge?” Matteson replied: “There is sir—one man.” Wilson quickly ordered: “We have to go get him or he will drown. Tell the gang to ready the lifeboat and you and I and another will be the crew.”

Again, the wind increased, with torrential rain. Near the lake, breathing was difficult because the air was so permeated with water from rain, while the wind lifted the lake’s surface water and combined it with the downpour. The U.S. Weather Bureau reported wind velocity at 95 miles-per-hour. We were used to reading speeds in statute miles so if the wind velocity was said to be blowing 95 to us it was over a 100 miles per hour. The rain now was a torrent, letting up once in a while to get a new start as Wilson observed. The screaming wind was deafening. The size of the waves on the lakeshore was very large and the sound of them hitting the shore was very loud.

The size of the seas created by wind action may be calculated by knowing the fetch of the wind. Fetch is the distance the wind blows over open water without obstruction. Other factors include how long the wind has been blowing and velocity; whether the water is salt or fresh; and the temperature of water. Waves at the extreme east end of Lake Ontario were much larger than anyone had ever seen. The wind had been blowing forever it seemed to the crew of the Galloo Island Lifeboat Station. The waves generated were extremely large and steep.

Wilson and Matteson were getting dressed for the ordeal ahead. Matteson asked who the other crewmember would be, and Wilson casually said, “Let’s take Gerrett.” The die was cast. Then Wilson asked a strange question: “Mr. Matteson aren’t you and Gerrett related?” Mr. Matteson replied: “I think so. He has Bullfinches and Nuttings in his family and so do I.” Wilson went on to say he knew my mother as a physicist. Matteson started talking to Wilson saying, “Have you thought this through Captain?” Wilson was the captain and it showed. He replied “I know exactly what you are thinking, the three of us will probably die trying to save one guy, who will die also. Get in the boat we have a job to do!”

The remainder of the station personnel, five guys, were trying their best to hold the boat while we boarded and clipped into our heavy weather harnesses. Meanwhile, they turned the boat around so it would be pointed in the proper direction for us to confront the terrible seas as they curled and crashed in the shallow waters of Galloo Island. The sound of the breakers crashing down on the point of land was terrifying. The lights on the dock and boathouse reflected off the top of the seas as they curled higher and higher—their immense size was terrifying. The wind velocity made it difficult to stand or walk. The terrible shriek of the wind grew much louder now.

When we climbed on the boat, its engine was purring softly as it idled, patiently waiting. It radiated confidence seemingly unperturbed by the frightful storm going on around it. The boat we used was known as a “motor lifeboat.” It was 36-feet long with an eight-foot beam. It was unsinkable with three watertight compartments and its exposed areas were self-bailing with scuppers. It was counter-capsize capable and its engine could run inverted. The keel weighed about a ton, and the boat had a communication system. This motor lifeboat was the right tool for a terrible storm such as this, and the man at the helm was the best man for this catastrophe. The feeling of the men on board was: If you can hang on, you may survive.

The master, Wilson, was in his safety harness at the helm while the mate stood beside him secured to the boat in his harness. I was in the same cockpit, attached to the aft towing bollard, clinching it as if I were some kind of human vise. An excellent boat operator, Wilson sensed the boat’s needs constantly, seeming to give it strength to fight the terrible storm. As we started out into the channel, the range lights were lined up perfectly. As we headed to open water, the lights from shore reflected off the seas as they broke on the sides of channel leading to the lake. Suddenly the rain stopped, the wave heights seemed to double instantly, and the breaking seas were mammoth.

There was no way Wilson was going to make his downwind turn without being pitch-poled end-over-end, killing us all. Yet, we all knew he would make the turn, come hell or high water—we were already enduring both. Matteson and I heard Wilson say to himself and to the storm: “If it would just rain like hell for a few minutes, we would be able to make the downwind turn without killing everyone.” And, as if by magic, a terrific rainstorm hit, the seas flattened out a little, and the downwind turn was made—we were on our way to catch the barge. We were also on our way into history—into the hurricane of September 1938. We had job to do.

Traveling downwind was a different story. The seas were traveling faster than we were, so we were now surfing and taking breaking sea after breaking sea over the stern. Hanging on to the bollard and getting hit with tons of water was not a nice thing to endure or a great place to find oneself.

Suddenly Matteson yelled “Did you see that? I just saw a light. It must be the light of the boiler fire as the door is opened as more coal is being fed to the fire. Happy day!”

The large dredging bucket that had been put over the side and was slowing the barge enough so we could catch her. As we approached the derelict, the gigantic boom was crazily swinging from side to side making an approach to the barge very hazardous. We made a few runs into the barge and, with a megaphone, called to the crewman to jump into the water, which he was very reluctant to do.

Wilson called to him saying we would send a line to him and to tie it tightly around his waist, and we would wait until the barge sank and he floated off. Then we would be able to retrieve him from the water as we had a line on him. As soon as we determined that he had the line tied to him, Wilson said “OK, let’s get him into the water and picked up. Then we will get out of here. I have had about enough of this hurricane.” The survivor was pulled off the barge and into the water. Eager hands from the lifeboat grabbed him and pulled him to safety. Wilson set a course for a safe harbor and there we stayed until the storm had subsided a little. We then returned to Galloo Island—mission accomplished.

After the rescue, the dredging barge foundered on a west facing rocky shore and was demolished. If the crewman had been on the dredging barge, he surely would have been killed. Saving the crewman’s life made it all worthwhile.

Editor’s Note: Four years after the harrowing Galloo Island rescue, Altson Wilson died with five other Coast Guardsmen aboard the picket boat CG-4229 during a heavy weather rescue in Oswego.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip:

National Coast Guard Museum visitors will be able to learn more about the history of Coast Guard search and rescue in the Modern Boat Rescue and Saving Lives by Air gallery on Deck 02 of the museum.