Coxswain for all invasions—Robert Ward and the Joseph T. Dickman at D-Day

From the Long Blue Line, by William A. Bleyer, chief boatswain, U.S. Coast Guard and James Paras, boatswains mate, U.S. Coast Guard, 1941-1946

Breadcrumbs

Subpage Navigation

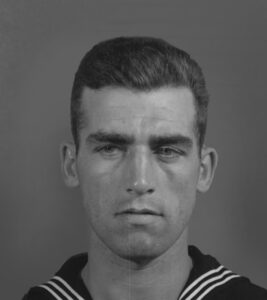

Robert Ward was a U.S. Coast Guardsman who distinguished himself as a landing craft crewman and Coxswain during multiple amphibious invasions in World War II. He was awarded the Silver Star Medal for combat valor and later became an officer.

Robert Grattan Ward was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on Sept. 23, 1916. He enjoyed playing basketball, football, and swimming. After graduating from Warren Harding High School in 1935, Ward served three years in the Connecticut National Guard with a coastal artillery unit. He then briefly worked as a grinder for the Aluminum Company of America and as a mail clerk for the U.S. Civil Service Commission in Washington, D.C. He enlisted in the Coast Guard on June 4, 1942.

Ward attended basic training at the Manhattan Beach Training Station in New York City. After graduation as an apprentice seaman, he was assigned to the Captain of the Port of Baltimore for port security duty. However, Ward likely wanted to see action, so he arranged a mutual transfer with a sailor named Marion Mugavero on the Coast Guard-crewed attack transport USS Joseph T. Dickman (APA-13). He reported aboard on March 13, 1943.

Credit: National Archives

The Attack Transport USS Joseph T. Dickman in 1942 with its original camouflage paint scheme. The transport was repainted haze gray within a year and remained that way the rest of the war.

The Dickman was one of many attack transports crewed by the Coast Guard during the war. By 1943, the attack transport had seen extensive service around the globe, beginning before the U.S. even entered the war in 1941 as well as the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942. At 535 feet long with a crew of about 50 officers and 700 enlisted men, the ship could transport up to 2,000 troops and 36 landing craft to disembark on hostile beaches.

When Ward came aboard the Dickman, he joined a crew of seasoned veterans, but he performed well as a member of the ship’s deck division. He was assigned primary duty as crew of one of the ship’s landing craft. He also attained proficiency with various small arms, including the Browning M2 machine guns mounted on the landing craft.

There were many craft employed for amphibious assaults in World War II. They ranged in the size from the ocean-going Landing Ship-Tank to the 36-foot-long Landing Craft-Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP). These various vessels would be essential for the reconquest of enemy-occupied territory in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean theaters of the war. Therefore, it was imperative that their crews be proficient at seamanship and navigation. The Coast Guard was a natural fit for these roles, and many were wholly or partially crewed by Coast Guard personnel.

Dickman crewman and Boatswain’s Mate, James Paras, described the landing craft:

“The Dickman’s [landing craft] were two types, LCVP and LCM’s. The LCVP, to which I was assigned, was made of Plywood, 36 ft. long, with a 10 ft. beam and propelled by a Gray Marine 225 HP Diesel engine. Had a flat bottom with forward draft of 2ft. and 3 ft. aft. Its top speed was 12 Knots (14 MPH), designed to accommodate 36 troops in its cargo well and had a steel ramp. The LCM was made of steel, 56 ft long, with a 14 ft. beam and powered by twin 225 HP Gray Marine Diesel engines. Could accommodate a 25-ton Army Tank in its cargo well.”

The Dickman sailed for Europe in May 1943 with Ward aboard. After crossing the Atlantic and training off England with U.S. Army Rangers, it headed for the Mediterranean.

Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, was dramatic for the Dickman. The transport anchored off Gela, Sicily, and landed Army Rangers, some crewmen got to see Gen. George Patton walk ashore nearby, and it later embarked wounded soldiers. During Husky, Ward likely served on the landing craft or on the ship’s deck assisting with launch and recovery.

Credit: National Archives

USS Dickman’s LCVPs, also known as Higgins Boats, landing equipment on the beaches of Sicily, Italy, as part of Operation Husky.

German bombers appeared overhead and attacked the invasion fleet. Anti-aircraft gunners on the Dickman fired at the German planes, apparently damaging three of them, and the ship sustained minor damage from bomb near-misses. Meanwhile, the nearby Liberty Ship SS Robert Rowan took three direct bomb hits. The Rowan was carrying a large amount of ammunition as cargo and was now afire. Its crew immediately evacuated as the Dickman weighed anchor to assist. Dickman’s landing craft picked up some survivors and its crew attempted to fight the fires. Soon, the Rowan detonated only 1,000 yards away from the Dickman; however, thanks to the rescue efforts of the Dickman and other nearby ships, there were remarkably no lives lost.

Credit: National Museum of the U.S. Navy

The Liberty Ship S.S. Robert Rowan detonating only a thousand yards away from the Joseph Dickman.

Ward and the Dickman next saw action at the invasion of Salerno, Italy. Despite the recent surrender of Italy, German forces had occupied the country and resistance to the landings was unexpectedly fierce. Several of the landing craft were hit by machine gun fire and the ship too. Aboard it were so many wounded and soldiers that “We were a mini-hospital ship,” as Paras put it. Whether he was manning the landing craft or on deck, Ward was cited for meritorious conduct during the two Italian amphibious assaults.

With yet another invasion complete, the Dickman shuttled troops around the Mediterranean before sailing back to the U.S. It then returned to Britian to prepare for the Allied invasion of Normandy, France, known more popularly as D-Day.

The story of the Allied amphibious landings on D-Day is often dominated by the horrific fighting that took place on the invasion beach codenamed Omaha. This intense combat between U.S. Army and German troops has been indelibly etched into popular memory by the movies such as “Saving Private Ryan.” However, while Omaha saw the worst fighting on D-Day, and the Americans sustained by far the most casualties, there were four other beaches assaulted that day, along with airborne landings inland. The British and Canadian armies landed at Sword, Gold, and Juno. The other American beach was codenamed Utah, and it would prove a career highlight for Seaman First Class Robert Ward.

Paras described the D-Day invasion and preparations for it:

“We took on cargo and returned to England, at Slapton Sands, where we began preparing for the Normandy Invasion. We practiced small scale landings on the British coast and made five full scale landings at Slapton Sands, where the beaches were similar to those at Normandy. On May 24 we reported to Falmouth, England, which was our base of operations. On June 2, 130 officers and 1800 enlisted men, were embarked for the coming operation…

“Preparations continued. The Army Intelligence group came aboard and gave a last-minute report on what was on Utah Beach. They had Charts. Photos and Models of the beach. And we received a detailed briefing. After they left, all ships were placed on Lock Down. No one was permitted to leave. Security was tight.

“Turned out weather was a big factor, was stormy with rough seas in the channel and Gen. Eisenhower decided to delay the landing until June 6, since conditions were predicted to improve. At 4:00 AM on June 6 all boats went in the water. Those in the Davits were loaded, then dropped in the water, while the rest were loaded via the debarkation nets. No easy task in rough seas. All barges ran over to their assigned areas, then ran around in circles, waiting till all boats were loaded. The troops in the boats were taking a beating, were not used to bobbing around in heavy seas and most were sick, along with getting soaked by the seas coming over the bow. At 0500 the signal was given, and we headed to the beach, had 12 miles to go. The ships were anchored offshore, out of the range of the guns on the beach.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard

With cargo nets dropped and LCVPs in position, the Joseph Dickman disembarks troops for amphibious landing.

“We passed the Battleship Nevada, on our route and they were firing their 16-inch (sic) guns. Could see the projectiles, as they left the muzzle and sailed over our heads. As we got closer, saw more Navy Ships firing their big guns. Rockets from the Rocket Firing Barges were Swishing overhead. And we prayed we didn’t get hit, by those falling short. The sky was covered with bombers heading to the beaches. I read one reporter’s description, said it was, “the Greatest Fireworks Display Ever,” and I totally agree.

“Was hard to believe there was anything left on beach, after that pounding but there was fire coming from those pill boxes and boats were getting hit. We passed troops clinging to wreckage but could not stop to pick them up. At 1000 yards off the beach, our Wave got the signal from the Control Boat, and it was full speed to the beach. Fortunately, we were able to give our troops a good landing, but other boats were not so lucky, landed at spots with giant holes, caused by the bombing, resulting in troops having to wade through deep water.

Credit: National Archives

American troops disembarking from an LCVP at Utah Beach during the D-Day landings.

“After debarking the troops, we backed down and headed to the Dickman. On our way we picked up four troops out of the water. All but seven of our boats made it back, were either swamped or damaged by gunfire. The ship took on thee dead and 154 casualties that were treated in our Sick Bay. We left Utah Beach and returned to Falmouth, where we unloaded the casualties and took on cargo, to return to Utah.”

Robert Ward was a coxswain of one of the landing craft. Everything that went wrong at Omaha Beach seemed to go right at Utah. President Theodore Roosevelt’s son Theordore Roosevelt, Jr., serving as brigadier general, famously disembarked with the first wave of troops in the wrong location, realized it was better than the planned one and declared, “We’ll start the war from right here!”

However, while the landings went better than expected, there was some German opposition, and Ward happened to be in the thick of it. At one point he reportedly used to his expertise with firearms to unjam one of the machine guns mounted on his boat and returned effective fire. The rest of his actions that day are reflected in his Silver Star Medal citation:

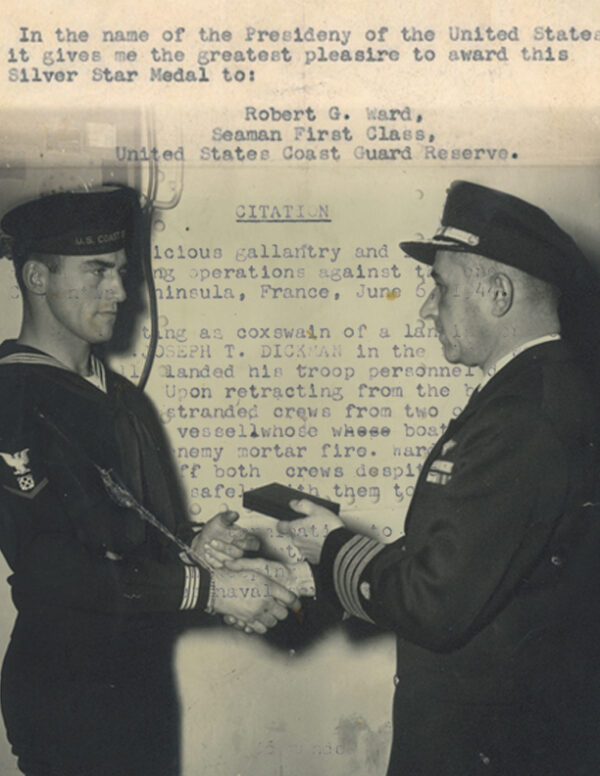

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as a Coxswain of a Landing Craft, attached to the USS JosEph T. Dickman, in operations against the enemy on the Cotentin Peninsula, France, June 6, 1944. Successfully landing his troop personnel during the first invasion wave, Ward, retracted from the beach, observed the stranded crews of two other landing craft whose boats had been destroyed by enemy mortar fire. Despite continued shelling, he returned to the beach rescuing both crews and taking them safely to the ship. By his skill, courage, and devotion to duty, Ward contributed materially to our success in this historic Campaign and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard

Coast Guard photograph of Robert Ward receiving the Silver Star Medal with the official medal citation listed in the background.

Ward’s performance was further recognized with meritorious advancement to coxswain (the wartime equivalent of BM3) on July 11, 1944. Now a petty officer, he saw action again as a landing craft coxswain when the Dickman returned to the Mediterranean to participate in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France. The landings in Southern France faced significantly less opposition than the ones in Normandy.

The Dickman’s war was far from over. After taking part in every major amphibious operation in the European-African theater, the transport would see action in the invasion of Okinawa in the Pacific. But by then, Ward was no longer aboard.

Capitalizing on his recognition, Ward applied to and was accepted for the Coast Guard Reserve Officer Training Course, today known as Officer Candidate School. He reported to the Coast Guard Academy on Feb.13, 1945, with class 2-45 and graduated 16 weeks later as an ensign in the Coast Guard Reserve. His first assignment as an officer was to USS Swiftsure (ex-Lightship 113), in Ketchikan, Territory of Alaska.

Ward probably did not enjoy the mundane duty on a lightship, especially in an area as remote as Ketchikan in 1945. He requested a transfer back to a more dynamic unit. Despite his excellence as a coxswain and a promising start, he did not excel as an officer. He was serving as the Weapons Officer when a .38 revolver was lost and presumed stolen from his lightship’s armory. This resulted in his receiving a letter of reprimand. Probably due to this incident, he was evaluated as “definitely not recommended for retention in the Regular Establishment.” Following brief service on the transport USS Cavalier (APA-37) and decommissioning of the USS Kanawha (AOG-31), he left active duty in 1946 at Training Center Alameda.

Robert Ward passed away in Florida in 1987. His heroism and service stand as a proud part of the long blue line.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard

The Coast Guard’s Fast Response Cutter Robert Ward on its maiden voyage in 2019.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors will have the opportunity to learn more about Coast Guard crewed landing craft and Operations Torch, Overlord, and Dragoon in the WW2 exhibit on Deck03 of the museum.