Throughout the history of the U.S. Coast Guard’s aviation branch, service aircraft have come to the aid of the American public in emergencies and in time of need. However, the Holiday Season has provided a unique opportunity for private citizens to return the favor.

Beginning in the Great Depression, aviator William “Bill” Wincapaw began the tradition of “The Flying Santa.” Born in Friendship, Maine, Wincapaw oversaw flight operations for the Curtiss Flying Service in Rockland, Maine. He came to admire Maine’s lighthouse keepers and their families for standing the watch in isolated and often inhospitable locations.

To show his appreciation for their dedication and self-sacrifice, Wincapaw decided to deliver gift parcels to local lighthouses on Christmas Day. Early in the morning Dec. 25, 1929, Wincapaw loaded the packages of Christmas gifts into his vintage Travel Air A-6000-A airplane, featuring a single radial engine and wicker seats. That first year, he airdropped Christmas gifts to a dozen lighthouses located along the Maine Coast.

Wincapaw continued the tradition the next year and, over time, came to be known as “The Flying Santa” and the “Santa of the Lighthouses.” He began to dress the part and enlisted his son, Bill Jr., to pilot additional Christmas Day flights. His gift parcels included basic items, such as newspapers, magazines, coffee, tea, candy, tobacco, soup, yarn, pens and pencils. By 1933, the program proved so popular that Wincapaw expanded it to include 91 lighthouses from Maine to Rhode Island and Connecticut. He even found commercial sponsors to underwrite the cost of the parcels and the flights.

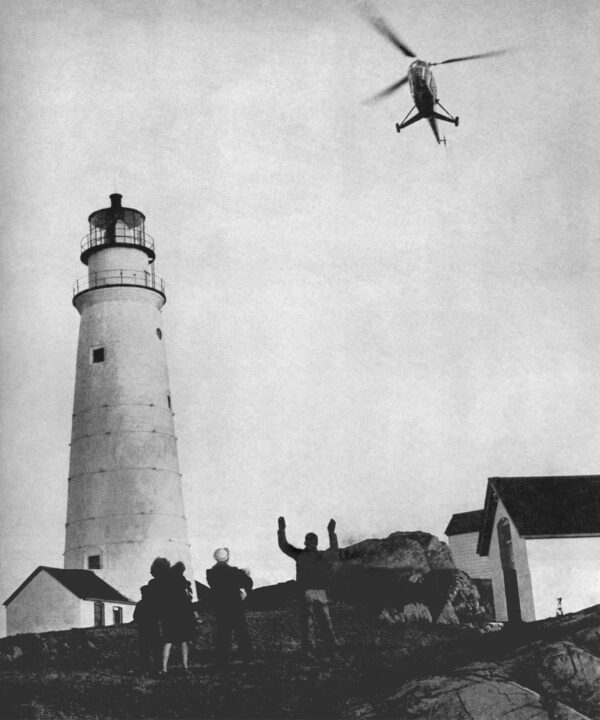

In the late 1930s, the program expanded requiring the services of a third Santa. The Wincapaws enlisted New England maritime historian Edward Rowe Snow to fill the position. During World War II, deliveries became more sporadic; however, by war’s end the Flying Santa visited an impressive 115 lighthouses and Coast Guard stations. In 1946, the program even tested the latest aviation technology using a helicopter to assist in airborne deliveries. The Flying Santa reverted to fixed-wing aircraft the next year and helicopters would not be used again for over 30 years.

In 1947, Wincapaw suffered a heart attack during a flight out of Rockland and died in the ensuing crash. Numerous lighthouse keepers, their families, and representatives from the Coast Guard, Army and Navy attended Wincapaw’s memorial service. At the appointed time of the service, foghorns and lighthouse warning bells called out along the Maine Coast to honor the man who established the beloved Flying Santa tradition.

After Wincapaw’s passing, Snow took over the program, and Snow and his family became the heart and soul of the operation. With the support of dedicated pilots, Snow honored Wincapaw by expanding the flights to include nearly 180 lighthouses and boat stations. In certain years, the program even served installations along the shores of the West Coast and Great Lakes; and remote locations, such as Bermuda and Sable Island, 100 miles off the Nova Scotia coast.

Snow continued the Christmas tradition for 45 years. He retired in 1981, when failing health prevented him from taking part in Flying Santa missions. That year, oversight of the Flying Santa program passed to the Hull Lifesaving Museum and helicopters replaced fixed-wing aircraft to transport the Flying Santa.

In 1987, lighthouses underwent automation; however, the Flying Santa continued to visit Coast Guard bases and installations. In the 1990s, a number of retired Coast Guardsmen began volunteering to serve as the Flying Santa. And, in 1997, the all-volunteer Friends of Flying Santa was organized as a private non-profit to run the Flying Santa program.

The Flying Santa has been in operation over 90 years since Captain Wincapaw founded it. Over the years, the Flying Santa has missed only the year 1942, due to the security concerns of World War II. Today, the program delivers gifts to over 800 Coast Guard children at 75 units located from Maine to New York. The Flying Santa remains a part of Coast Guard legend and the lore of the long blue line.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will have opportunities to learn about the lives and histories of lighthouse keepers in the Lighthouse Theatre exhibit in Deck 4’s Champions of Commerce wing!