The history of African American participation in the Coast Guard and its predecessor services dates back to the very founding of the Service in 1790. In over 225 years of Coast Guard history, African Americans have been the first minority group to serve, first to fight and the first to sacrifice. In fact, the first known service death in the line of duty was a Black cutterman lost off the cutter South Carolina in 1795.

During the early years of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, many African American cuttermen were slaves as well as free men of color. Regardless of their status, Black people served side-by-side with their white shipmates. In the Quasi-War with France of the 1790s and the War of 1812, African American cuttermen were among the first to fight against Royal Navy warships. At age 15, a Black cutterman captured off the James Madison, a War of 1812 cutter is considered the youngest prisoner-of-war in Coast Guard history. And, in 1836, the service experienced its first African American combat loss when assistant keeper and freedman Aaron Carter died defending the Cape Florida Lighthouse against a Seminole Indian attack.

War often serves as a catalyst for cultural change, and it did for African Americans in Coast Guard predecessor services. During the Civil War, Black people comprised 5 to 10%of the crewmembers on board revenue cutters. Given the small size of cutter crews, this proved a de facto form of integration. As the status of countless African Americans changed from slave to freedman, the U.S. Lighthouse Service began hiring former slaves, or “contrabands,” to work at Southern installations. For example, in 1863, a contraband crew operated the Fishing Rip Lightship, near the captured city of Port Royal, South Carolina. Soon after the war, the Lighthouse Service hired African Americans to operate lighthouses in the Southeast and, by the late 1870s, Black keepers supervised some lighthouses while all-Black crews manned other lights.

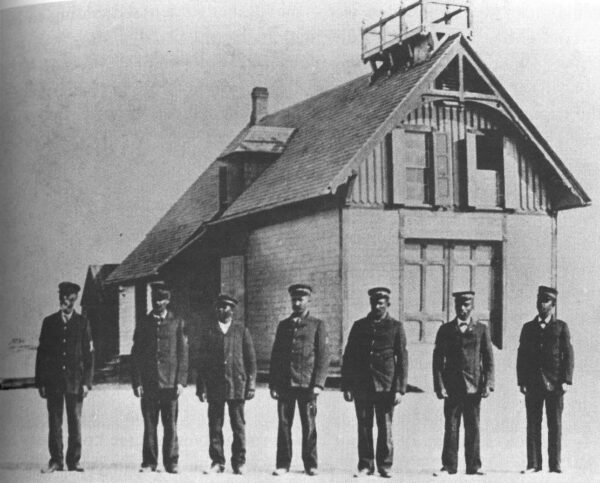

In the 1870s, the newly formed U.S. Life-Saving Service hired African American watermen along the southeast coast who were known for their boat handling skills in shallow water and heavy surf. As a result, the service assembled interracial “checkerboard” crews of white and Black surfmen. In 1875, five out of six surfmen in the crew at the Cape Henry Station were Black and, in 1876, African American Jeremiah Munden was among the service’s first surfmen to die in the line of duty. By 1880, the service appointed African American surfman Richard Etheridge as station keeper of the all-Black Pea Island Life-Saving Station. He was the first African American to oversee a Coast Guard station. In 1896, his Pea Island crew performed the Gold Life-Saving Medal rescue of survivors from the wrecked schooner E.S. Newman.

The late 1800s saw other opportunities for African Americans. Receiving a Revenue Cutter Service commission in 1865, “Hell Roaring” Mike Healy was the first commissioned officer and ship’s captain of African American heritage in the history of the nation’s sea services and he became famous in the 1880s and 1890s as the captain of the Arctic revenue cutter Bear. The Spanish-American War also served as a minority highlight of the late 1890s. The cutter Hudson’s steward, Moses Jones, and cook Henry Savage received specially struck Congressional Bronze Medals along with rest of the enlisted crew for heroic service in the hard-fought Battle of Cardenas Bay, Cuba. It was the first such recognition of African Americans in U.S. history.

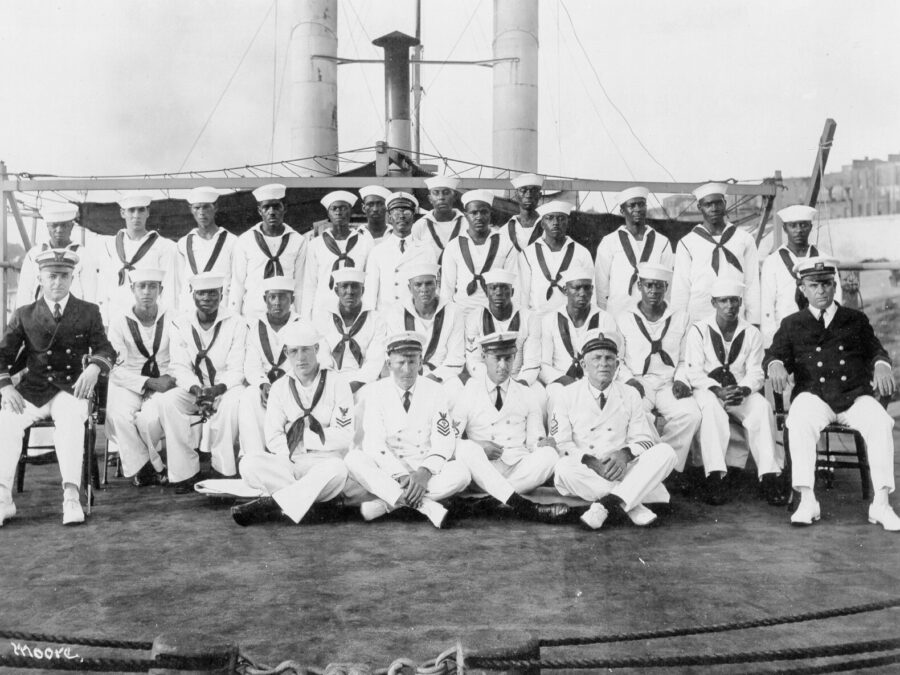

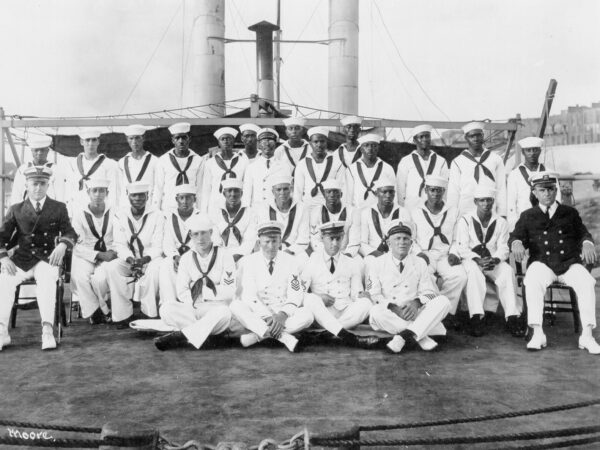

In the first half of the 20th century, African Americans enjoyed further advances in the service. Beginning in 1897, over 20 members of North Carolina’s Berry family served with approximately 400 years of total Coast Guard service and nearly 115 consecutive years served by one or more family members. In 1919, the Vicksburg-based cutter Yocona became the first integrated Federal ship in U.S. history. Her crew included white officers and non-commissioned officers with a Black enlisted force. By 1928, cutterman Clarence Samuels became the second African American in U.S. history to command a Federal vessel beside Captain Healy and, during World War II, Samuels would become the first Black officer to command a U.S. warship in a combat zone.

During World War II, the Coast Guard undertook the Federal Government’s first official experiments in desegregation. In 1943, the Coast Guard began sending African American officer candidates through its Coast Guard Academy-based Reserve Officer Training Program and commissioned its first African American officers. By late 1943, the Coast Guard assigned 50 Black officers and enlisted men to the Coast Guard-manned USS Sea Cloud. The experiment proved a success and set the standard for integration in other vessels of the U.S. naval services. Both the commissioning of African American officers and the Sea Cloud experiment came a year before similar milestones in the U.S. Navy. By 1945, the Coast Guard also appointed its third Black ship commander and five African American women enlisted to become the first Black females to don a Coast Guard uniform. African American war heroes received numerous honors and awards, including the Bronze Star Medal, Navy & Marine Corps Medal, Navy Commendation Medal, Silver Lifesaving Medal, and Purple Heart Medal.

By the end of the war, 5,000 Blacks had served in the Coast Guard with one of every five reaching petty officer or warrant officer levels. These men and women included Jacob Lawrence, a crewmember on board Sea Cloud, who became a famous modernist painter in the 1950s and, who went on to become a distinguished professor of psychology at Fordham University, retiring at the age of 87. Alexander “Alex” Haley enlisted in 1939 as a steward’s mate and rose to become the first chief journalist in the Coast Guard. After 20years, he retired to pursue writing and won awards as the author of such books as Roots and the Autobiography of Malcolm X. Later, he received the first honorary degree awarded by the Coast Guard Academy and became the namesake of a Coast Guard cutter. In 1945, Lt. j. g. Harvey Russell became the third African American officer to command a federal vessel. After he left the Service, he joined the Pepsi Cola Company and, in the early 1960s, he broke America’s corporate color barrier when he rose to vice president of that multi-national corporation. In 1943, Russell’s friend and Sea Cloud shipmate, Lt. j. g. Joseph Jenkins, received an invitation from the African nation of Liberia to serve as the civil engineer in charge of design and construction that country’s infrastructure projects. However, Jenkins remained in the service and, after the war, returned to his hometown of Detroit, where he oversaw construction of the city’s rapidly expanding freeway system. After the war, Coast Guardsman Emlen Tunnel became a professional football star with the New York Giants. He was the first African American inducted into the Professional Football Hall of Fame and experts today rank him as one of the 100 greatest players in NFL history.

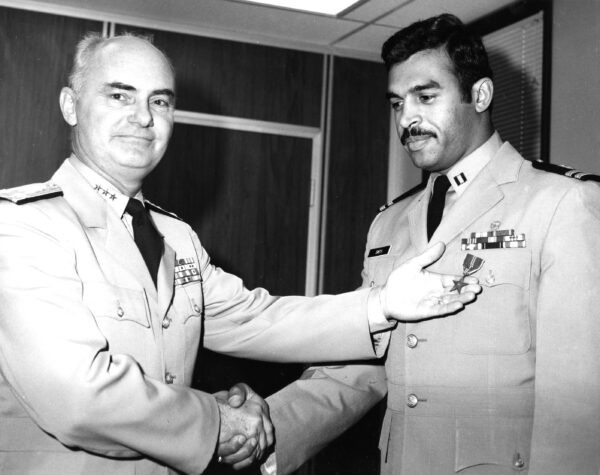

By the end of the war all enlisted rates were opened to African American recruits. But that advance was just the beginning as African Americans gained greater access and equality in all parts of the Service. The first Black graduate from Officer Candidate School, Lovine Freamon, was commissioned in 1954 and Bobby Wilks followed in 1956. Wilks later became a minority trailblazer in senior officer ranks and Coast Guard aviation. Javis Wright, the first African American cadet, entered the Coast Guard Academy in 1955; however, due to health concerns, Wright was unable to graduate from the academy. In 1966, Merle Smith became the first African American to graduate from the academy. As a cutter commander in Vietnam, Smith became the Service’s second Black recipient of the Bronze Star Medal. By the mid-1970s, African Americans made up 7% of the service, including individuals at the master chief and captain levels. African American women first graduated from the Academy in 1983 and dozens of Black women climbed the enlisted and officer ranks during the 1980s and 1990s.

Modern Time Firsts

In modern times, African Americans recorded numerous Coast Guard “firsts.” They achieved higher officer and enlisted levels and received assignments in numerous roles previously unknown to Black people. By 1998, Vince Patton became the first Black Master Chief Petty Officer of the Coast Guard, the highest enlisted rank in the service. That same year, Erroll Brown became the first Black flag officer, followed in 2002 by Stephen Rochon. In 2000, Angela M. McShan, became the first African American woman to achieve the enlisted rank of Master Chief Petty Officer. The first African American female aviator, Jeanine McIntosh, earned her wings in 2005 and, in 2009, Lt. Felicia Thomas took command of the Pea Island to become the first Black female to command a cutter. In 2010, Manson Brown became Pacific Area commander and vice admiral, the highest Coast Guard rank achieved by an African American.

Leading the Way

African Americans comprise the longest serving minority in the United States Coast Guard. They have pioneered the way ahead for all minorities in the Coast Guard, U.S. military, and the nation. While the Service celebrates highlights of African American service in the Coast Guard, it should recognize the accomplishments of hundreds of thousands of African Americans over the course of its 225-year history. These members of the long blue line have strived for equal rights and persevered with a dedication that has benefited all who serve in the United States Coast Guard.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The story of Black Coast Guardsmen will be woven throughout the museum, but the Pea Island narrative, specifically, will be located on Deck 2, as part of the story of the U.S. Life Saving Service.