Between February 17th and 18th, 1952, a hurricane, the likes of which have rarely been seen even in stormy New England, dumped more than 30 inches of snow. Travel was limited to emergency rescue crews. Stuck inside, people stayed glued to shortwave radios about a major story at sea: that of the broken 502-foot tanker Fort Mercer some 40 miles east of Provincetown, Massachusetts. Five larger Coast Guard cutters and a Navy ship were already engaged in full-scale rescue operations that would save 38 merchant seamen from Mercer. Known as T2 tankers, World War II-era ships like Mercer bore the moniker of “Kaiser coffins,” for their frailty in heavy seaways and cold temperatures.

A Coast Guard airplane dispatched from Salem Air Station supported the Fort Mercer operation. The plane stumbled upon a second broken 502-foot T2 vessel, the Pendleton, nearing the Cape Cod town of Chatham. Nearly identical to the Fort Mercer, the Pendleton, too, had broken in two. The radio room near the bridge had been destroyed, so the Pendleton crew could not send an SOS. The Coast Guard had situational awareness of two vessels in four pieces without knowing how many crewmen on each section of those ships. Station Chatham’s first and most experienced four-man crew was sent out to assist the Pendleton in the 36-foot motor lifeboat CG 36383. The Coast Guard crew found no survivors.

Back at Chatham, BM1 Bernie Webber had already put in a full day pulling grounded fishing vessels to safety when news came of the second distressed vessel. The Officer-in-Charge ordered Webber to form a crew since more experienced crew, wise to the significant risk, had made themselves scarce. Webber’s primary engineer was sick, so he selected the relatively junior Andy Fitzgerald and another Boatswain, Richard Livesey. The fourth crewmember, Ervin Maske, was a transient crewmember from the nearby Stonehorse Lightship, and was known for his baking, not his heroics.

Webber and his crew knew this could be their last mission as they drove the quarter mile from the Chatham Station to the Fish Pier in the late afternoon of February 18, 1952. Bernie ran into John Stello, a local fisherman. “Call Miriam [Webber’s sick wife] and let her know what’s going on,” Bernie asked him. “You guys better get lost before you get too far out,” Stello shouted. Stello’s meaning was clear. It was 5:55 p.m.

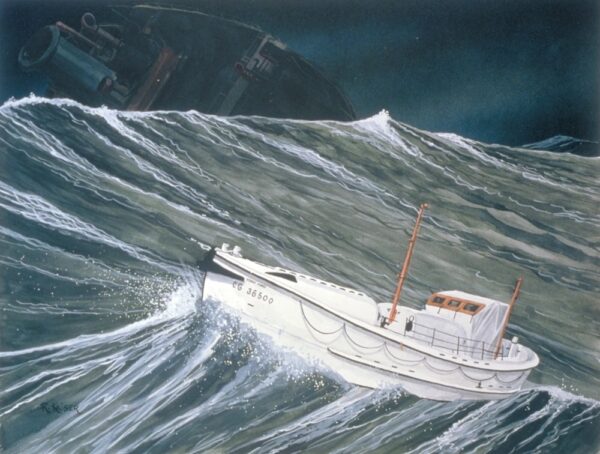

Webber and his crew boarded a dory and rowed to the moored CG 36500, a 36-foot motor lifeboat. It took a few minutes to get underway: unfasten lines to the anchor, fire up the single, 90-horsepower gasoline diesel engine, and check the throttle. Daylight was gone.

They passed the red blinking light of the buoy marking the entrance to Old Harbor. Approaching the notoriously dangerous Chatham Bar, the crew sang Rock of Ages, Maske’s favorite, and Harbor Lights. Aboard the Pendleton, about five miles outside of Chatham, it was chaotic remembered Charles Bridges, at 18, the youngest seaman. Earlier, when the T2 tanker split in half late on February 17th, Bridges awoke to odd grinding noises. “We had no idea the ship had broken into two,” he recalled.

The Pendleton crew lived minute to minute, not knowing whether the stern section would sink, drowning the surviving 33 crew in the stern. All they could do was wait.

Meantime, “the first sea over the Chatham bar hit us, picked us up, turned us around and threw us back into the harbor,” Bernie recounted. “Breaking seas over the lifeboat in through the windshield opening along with the violent motion of the boat tore the compass from its mount,” remembered Bernie. To add to their worries, “the windshield was smashed in, shattering into a million pieces,” Webber added.

He struggled to regain control of the CG 36500 and steer into the waves. Finally, the wave heights had increased—and Bernie knew he had crossed the bar. Nearby cutters involved in the Fort Mercer and Pendleton rescues reported sea heights up to 60 feet. Bernie kept going and motored into the lap of the nor’easter.

Bernie wore no life jacket. “It would have been too confining,” Webber remembered. Andy Fitzgerald recalled that “After we got over the bar the boat rocked and rolled, but it wasn’t violent enough to lift us off the deck, and I thought we’d be okay if it didn’t get worse.”

Aboard Pendleton, despair rippled through the ranks. The Pendleton’s engineer and his crew sensed imminent death each time the stern hulk hobby-horsed southward, smashing bottom with each new series of waves. Although several Coast Guard cutters were nearby, only CG 36500 was in any position to attempt a rescue of Pendleton’s men.

The 36500 labored up one side of a huge wave then surfed down the backside, accelerating towards the trough. Webber knew too much speed was unwise, and the boat’s bow could be buried in the next wave, swamping it. The boat’s motion was so swift Bernie reversed the engine on the backside of each wave to slow the CG 36500. The weather and visibility worsened as freezing horizontal snow tore at Bernie’s raw face through the broken windshield.

Every so often the lifeboat’s engine conked out when waves rolled the CG 36500 over and the gasoline diesel engine lost its prime. Each time, Fitzgerald crawled into the cramped compartment and restarted the engine. His efforts were rewarded with severe burns, bruises, the steady chug-chugging of the engine and the collective sighs of appreciation from his shipmates.

When asked how he knew he’d found the Pendleton, Bernie simply said, “Don’t know. First, I knew of it, I heard it. This rumbling, crashing, banging sound over the wind and the sea. And I sensed ‘Geez, there’s something there.’” If the seas and wind knocked out the compass and windshield, thankfully the small searchlight proved a godsend. The searchlight revealed the Pendleton dead ahead, a black mass of twisted metal heaving high into the air atop massive seas, settling back with a thud into “frothing mass of foam,” said Bernie. Divine intervention, dead reckoning and plain luck have all been trumpeted as ways Bernie’s crew found the Pendleton that night. “I was looking right into where it was broken in half. Just a white crawling mess and it would just rear up high in the water, and then settle back down with a crashing and a banging,” added Webber.

Webber motored down the port side of the stern hulk. No lights were on, and the railings were “kind of bent and smashed and I could see signs of damage, and I says, ‘geez, maybe no one’s on board, there’s no lights on or anything.’ As I found the stern, I made out the name Pendleton, and knew for sure what I’d found. Went around to the starboard side and by God there were lights on, deck lights shining a little yellow glow up there.”

The hulk towered over the small CG 36500. Andy Fitzgerald remarked, “I wondered how we would get anyone off.” “I saw one man, he looked about the size of an ant, standing at the rail,” said Webber. “My first reaction was ‘Holy shit, we came all this way for one guy! Four of us, we came for one guy!’”

A few seconds later more Pendleton crewmen lined the rail and threw over a Jacob’s ladder. Webber looked at it and thought, “Maybe we ought to get off this lifeboat and get on that ladder and climb up, but before I could think much more about it, they started coming down, they wanted off,” Bernie recounted. The first man at the bottom dropped in the water and was lifted 50 feet when the Pendleton rolled and heaved. Webber told his crew to assist the first survivor.

Each Pendleton crewman required at least one pass of the ladder, and Bernie occasionally made several to get one man aboard. “I had to make several passes. Those guys at the bottom of the ladder, there had to be two or three others somewhere on that ladder. You could only get one guy at a time off that ladder, and I’d have to judge and see. If I got in there at the wrong time, I could come up underneath him, with the lifeboat and hurt him badly,” he said. “Just to maneuver up alongside, it required constant work with your left-hand steering, with your right-hand throttling in and out of gear back and forth,” Webber remembered.

With finite skill, remarkable for a boatman with just six years’ experience, Bernie maneuvered the CG 36500 along the Pendleton’s starboard quarter. One by one, the merchant mariners either jumped and crashed hard on the tiny boat’s bow, or fell into the freezing, churning water where Andy, Ervin and Richard plucked them aboard at great personal risk.

Some Pendleton crewmen were sling-shotted out from the ship on the Jacob’s ladder by the whipping and rolling motion of the waves. As soon as they had reached their zenith of flight, the ship would snap roll them back, violently, slamming them against the side of the tanker. Somehow, they had brought aboard all but one of the 33 Pendleton crew. One was crushed by the rescue boat and drifted off.

Bernie described his lucky stroke of providence: “after I got the last guy off, all of a sudden that ship came down at us, just like this,” he said, motioning with his hand, “and it dawned on me, ‘that ship is gonna capsize and take us all,’ then the Pendleton rose up, rolled hard to port and disappeared” without affecting the rescue boat.

Lost in zero visibility with no compass and 36 men aboard the overloaded boat, Webber made a critical choice. The CG 36500 motored into the night and the Coast Guard crew was on the lookout for anything: lights, land or marked buoys. “As luck would have it, we found a little buoy on Chatham Bar” and that small red light never looked so beautiful. It was the buoy on the inside of the Chatham Bar, at the turn marking the entrance up into Old Harbor and safety.

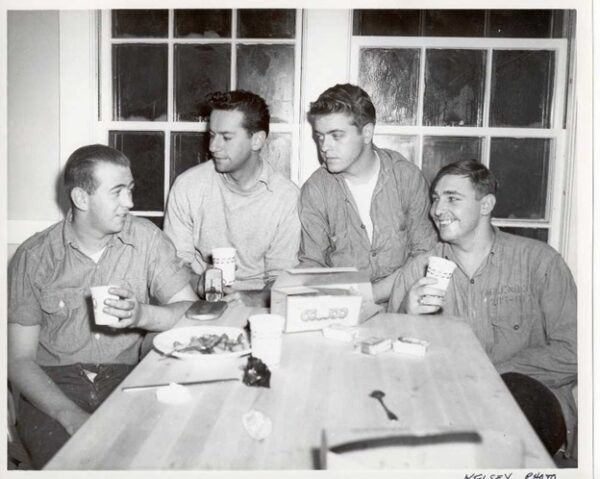

In May 1952, all four CG 36500 crewmen were presented with the Gold Lifesaving Medal and, to this day, Webber’s crew is referred to as the “Gold Medal Crew” involved in the greatest small boat rescue in Coast Guard history.

In May 2009, aboard a Coast Guard jet en route to Washington, D.C., then-Commandant Admiral Thad W. Allen, and then-Command Master Chief Skip Bowen made the plan to name the new fleet of Fast Response Cutters (FRC’s) after enlisted heroes. Their decision came hours after Admiral Allen and Master Chief Bowen attended funeral services on Cape Cod for Chief Warrant Officer Bernie Webber, the coxswain of the iconic CG 36500, whose crew saved 32 seamen from the floundering 502-foot tanker Pendleton, on February 18, 1952.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip:

National Coast Guard Museum visitors will be able to see a piece of CG-36500 and learn about the Pendleton rescue in the Lifesavers Around the Globe wing on Deck 02 of the Museum.