Those familiar with Coast Guard history know that the service’s development has been shaped by the nation’s natural and man-made disasters. Many Coast Guard missions were written in blood. Nowhere is that clearer than the marine safety mission.

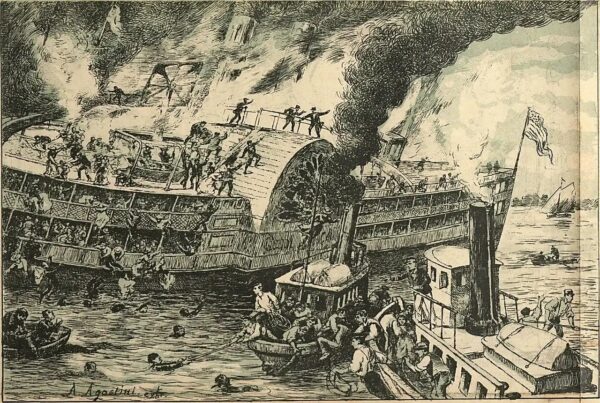

Sultana

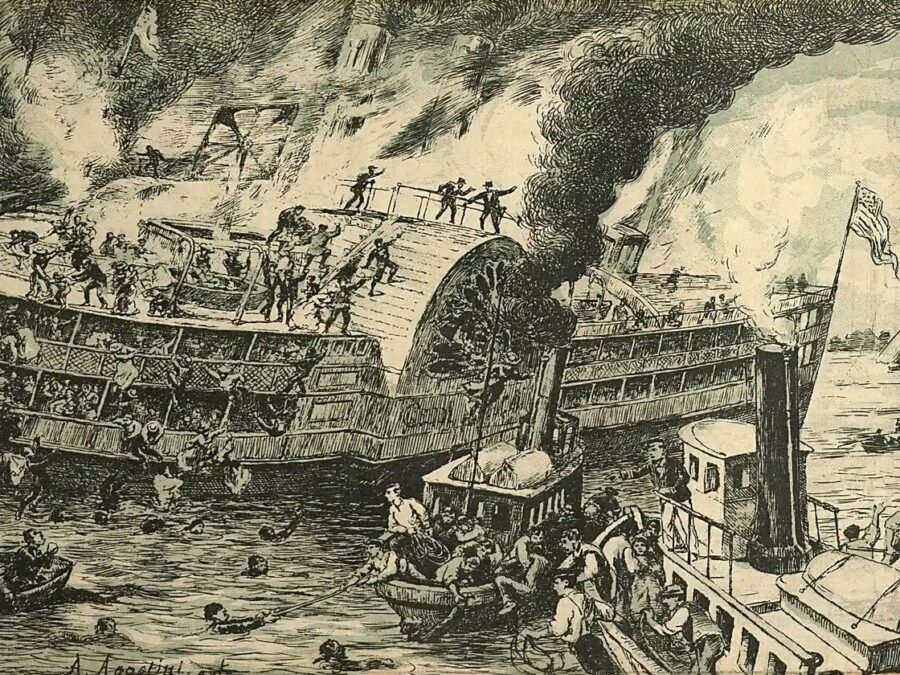

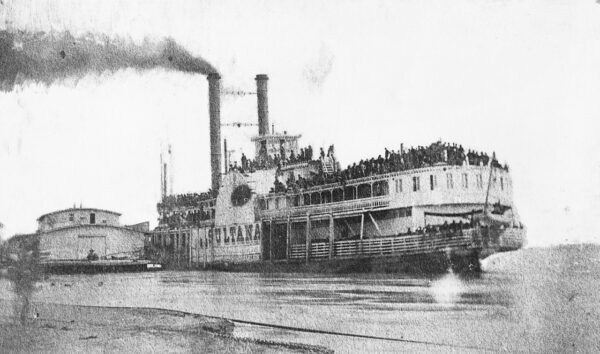

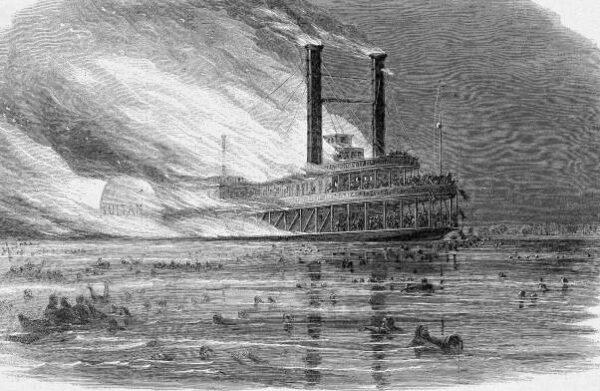

In the early morning hours of April 27, 1865, Sultana, a 260‐foot wooden‐hulled steamer, exploded on the Mississippi River near Memphis. This steamer had the legal capacity to carry 376 passengers, but Sultana was carrying more than 2,400! Tragically, the majority of passengers were Union soldiers who had been recently released from Confederate prison camps and were returning to their Midwestern homes.

The explosion happened so swiftly that many victims literally dove through flames into the Mississippi to avoid certain death. Some estimates place the total loss of life at 1,800, almost 300 more than in the much more well‐known Titanic disaster 47 years later. One survivor recounted that:

such screams I never heard – twenty or thirty men jumping off at a time – many lighting on those already in the water – until the river became black with men, their heads bobbing up like corks, and then many disappearing never to appear again. We threw over everything that would float that we could get hold of, for their assistance; and then I, with several others, began tearing the sheeting off the sides of the cabin, and throwing it over.

The disaster was made worse by several factors. First, Sultana was badly overloaded. There was just one lifeboat on the vessel and after the lifeboat was tossed into the river, one hundred or more men struggled to hold on or to get inside. Under the weight of so many men, the lifeboat sank into the river. At the board of inquiry, the pilot said that Sultana was “fully supplied with life preservers. A total of 76.” In addition, according to witnesses at the inquiry, Sultana’s boiler was damaged and needed more repairs than what it received at Vicksburg. R.G. Taylor, who repaired the boiler at Vicksburg, said that the captain was in a hurry to get Sultana back on the river and did not want to take the time to make the necessary repairs. This needless tragedy—which still stands as the worst marine disaster in American history—made it only too clear that more oversight was critical.

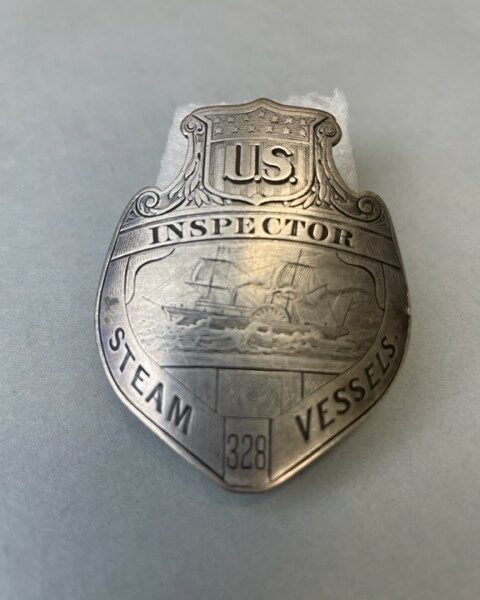

The Act of 1871 establishing the Steamboat Inspection Service

The Act of February 28, 1871, (16 Stat. 458) addressed some of the limitations of the Steamboat Act by firmly establishing the Steamboat Inspection Service with a central office in Washington dedicated to navigational safety. Under the Treasury Secretary, a Supervisory Inspector General would now manage all nine inspectors in each district. The act provided inspectors with broader authorities, such as authority to:

- regulate all steam‐powered vessels (excluding public vessels)

- protect passengers and crews

- require licenses for all masters, and chief mates; to revoke licenses

- prescribe nautical Rules of the Road.

Further, in June 1872, shipping commissioners were placed at specific ports. On July 5, 1884, the Bureau of Navigation was created within the Treasury Department. The new agency enforced laws connected with the construction, operation, equipment, inspection, safety, and documentation of merchant ships. Moreover, the Bureau investigated marine accidents, collected taxes and navigation fees, and examined, certified, and licensed merchant seamen. The Act of February 14, 1903, (32 Stat. 825) created the Department of Commerce and Labor, and the Steamboat Inspection Service was transferred from the Treasury Department to this new department.

General Slocum

The following year, on June 15, the excursion steamer General Slocum caught fire in New York’s East River, causing the death of more than 1,000 people, the majority of which were women and children. This disaster produced the largest loss of life in New York in a single day until more than 2,700 people lost their lives in the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. An outraged President Theodore Roosevelt immediately ordered an investigation, which revealed that the General Slocum catastrophe could have been avoided had the vessel’s captain equipped the vessel with adequate and working firefighting equipment, conducted fire drills, and conducted firefighting training for the crew.

The General Slocum became a means for improvements in the steamboat safety regulations, which led to a reform of the Steamboat Inspection Service. One month prior to the calamity, General Slocum passed a safety inspection. The steamboat inspectors never should have passed the vessel. Soon after, Roosevelt fired all of the Steamboat Inspection Service officers who were involved in the General Slocum’s inspection. Additional safety requirements that were subsequently enacted included the following:

- fireproof metal bulkheads

- steam pipes to extend from the boiler into the cargo areas to act as a sprinkler system

- better lifejackets and one for each passenger and crewmember

- easily accessible lifeboats

- improved fire hoses with a 100‐pound pressure capacity. by the Coast Guard.

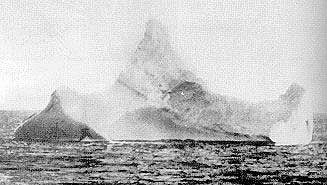

Titanic and Eastland

On its maiden voyage, on April 14, 1912, the luxury‐liner Titanic ran into an iceberg and sank in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, taking 1,513 passengers and crew to their grave. This disaster was the catalyst for the International Convention of Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in 1914. It was evident that Titanic did not carry enough lifeboats to accommodate the number of passengers and crew. The convention’s main goal was to adopt lifesaving devices geared to protecting lives at sea such as ensuring passenger vessels carried adequate numbers of lifeboats for its complement of crew and passengers, watertight hull subdivisions, and radio communications. Loss of the Titanic also led to the establishment of the International Ice Patrol; another mission undertaken by the Coast Guard.

World War I saw the suspension of the International Ice Patrol and iceberg monitoring by the Coast Guard. In addition, the first International Conference on Maritime Safety, initiated by the Titanic disaster had convened in London in 1914. However, the outbreak of World War I also prevented full development of the Convention’s recommendations and preventable accidents continued to occur world-wide.

One year later, on July 24, 1915, Western Electric Company employees never dreamed what would happen when they chartered the excursion steamship Eastland on a warm Chicago day. With 2,500 people on board, Eastland broke from its moorings, drifted, and then turned to port. Eastland floated on its side for a few minutes before sinking in shallow water taking 812 people to their deaths. It was later determined that “improper procedural methods in the control of the vessel’s stability” caused the vessel to roll over. Legislation was later introduced in Congress as a direct result of this deadly accident.

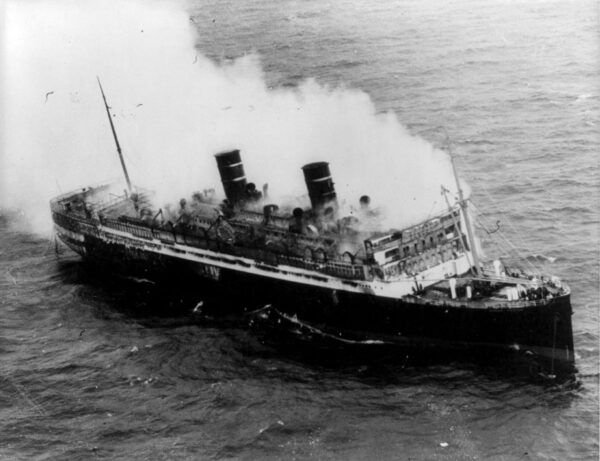

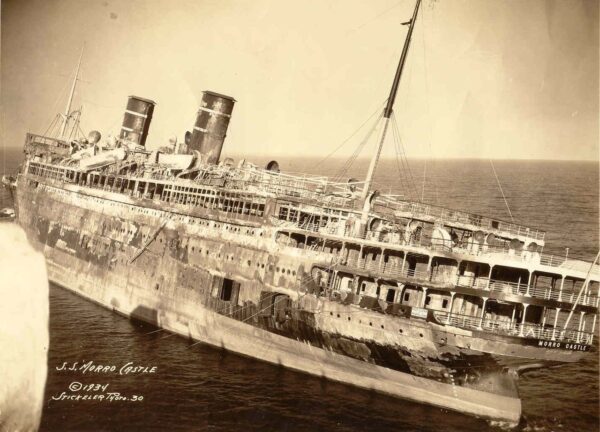

Morro Castle and Mohawk

Continued legislation and congressional mandates would not prevent two more high‐profile maritime disasters. On Sept. 8, 1934, the 508‐foot luxury liner Morro Castle, enroute from Havana, Cuba, to New York, burned at sea, killing 124 people.

The ensuing investigation found many safety inconsistencies concerning the vessel’s firefighting equipment and further discovered that the crew had not received proper firefighting training.

Less than five months later, on Jan. 24, 1935, the passenger vessel Mohawk collided with the Norwegian motorship Talisman, killing 45 people. In response to these accidents, more legislation was passed between 1936 and 1937 than in the previous 20 years. Congress would now regulate three categories regarding passenger vessel safety:

- passenger ship structure, equipment, and material

- they would define the number of officers and crew necessary to safely operate a vessel

- the Federal government would supervise the merchant marine

Moreover, this new legislation required that all marine casualties involving regulated vessels be reported and investigated.

The Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation

The Act of May 27, 1936, reorganized and renamed the Bureau of Navigation and Steamboat Inspection as the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation (BMIN). The Bureau remained within the Commerce Department. It continued to enforce the laws and regulations of its predecessor agency; however, the 1936 Act authorized the creation of a marine casualty investigation board and prescribed rules and regulations to investigate marine casualties.

As a result of World War II, a final shift occurred, when President Franklin Roosevelt transferred the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation to the Coast Guard. Under Roosevelt’s reorganization plan, the transfer outlasted the wartime emergency, and the bureau never returned to the Commerce Department. In 1946 the shift was made permanent.

With that shift, all the responsibilities for maritime safety were centralized into the U.S. Coast Guard. A new strategy emerged for studying and implementing new safety measures for navigation and protecting lives and property. The service took the lead as the central federal agency responsible for the safety of life and property both at sea and on the navigable waters of the United States.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will have the opportunity to learn more about the long and important history of marine safety regulations in Deck04’s Marine Safety exhibit.