Lewis had to make what he considered to be one of the most crucial decisions of his life. Peering at the fog below him, he remembers asking himself a question to plunge or not to plunge…

On Feb. 12, 1971, an HH-3F CG-1473 assigned to Coast Guard Air Station San Diego and crewed by Lt. Cmdr. Paul Lewis (aircraft commander), Lt. Joseph Fullmer (copilot), ASM3 Larry Farmer , AT3 Charles Desimone, and HM3 Richard McCollough launched in response to an injured or ill “seaman in need of an operation” on board the 492-foot freighter Steel Executive, approximately 220 miles south of San Diego. The World War II-era Type C3-Class cargo ship owned by Isthmian Lines of New York was on an extended trip from Saigon, South Vietnam, to New York City via the Panama Canal with stops in other East Coast ports. It departed Saigon on Jan. 29, 1971, and on Feb. 12, it was southbound for the Panama Canal. After requesting assistance, the ship reversed course back toward San Diego to reduce transit distance for the helicopter. This is their story.

Friday afternoon at around 4 p.m., Rescue Coordination Center Long Beach launched the off-going Air Station San Diego HH-3F duty crew on a long-range medical evacuation or MEDEVAC. The maintenance crew had to stop downtown vehicle traffic so that CG-1473 could taxi from the unit’s waterfront location across Harbor Drive to Lindberg Field in order to utilize the runway for a running takeoff—as the aircraft could not get airborne from a hover with a maximum fuel load. According to Lewis, taking off “out of San Diego, it was a clear afternoon,” but the sun was lowering in the sky with official sunset at 5:31 p.m.

After two hours of night overwater navigation and using a combination of radio direction finding, helicopter radar, and guidance from the Steel Executive, CG-1473 arrived in the vessel’s vicinity, but was unable to make visual contact through the dense fog, which extended from the surface to about 700 feet above the water.

Flight mechanic Larry Farmer described the scene:

“We flew over the estimated position at 1,500 feet and it was beautiful, you could see stars clear to either horizon, but glancing down—it looked like a huge layer of thick cotton blanketing the water below us.”

With visibility less than 1/8 mile, the helicopter directed the vessel to turn on all available topside lighting and dropped two MK-58 marine location markers (floating cylinder that produces smoke and flames for 40 to 60 minutes) approximately two miles downwind to assist in executing an instrument approach to a hover above the water’s surface.

Lewis had to make a crucial decision. Peering at the fog below him, he remembers asking himself a question to plunge or not to plunge. Lewis knew that the answer could spell a chance at life for the seriously ill merchant seaman. However, there was also his crew, his co-pilot, a radio operator, a corpsman, and the aviation survivalman who operated the rescue hoist. Their lives and his own also were at stake.

“I decided to lower the helicopter down to the water,” he said in an interview. “By then it was pitch dark. I flew away from where our radar told us the ship was and then went down to about 40 feet from the ocean.”

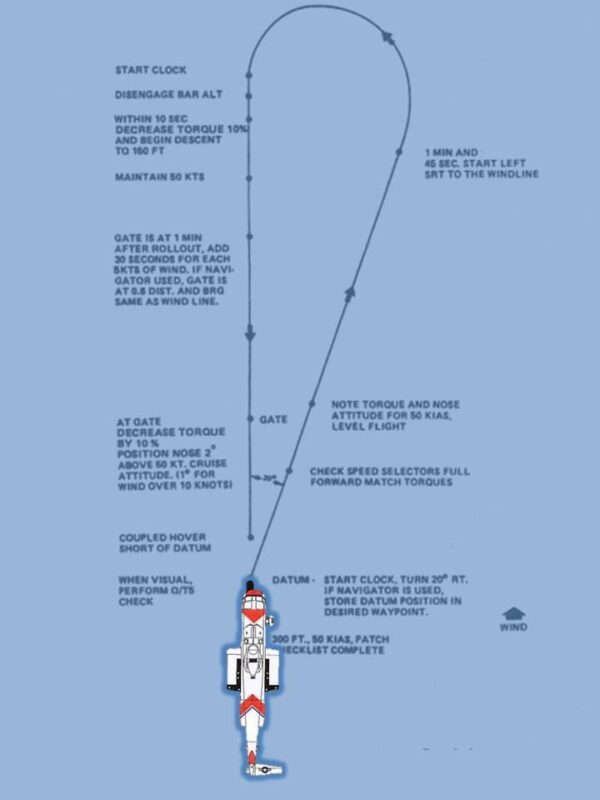

To transition from forward flight to a hover, CG-1473 executed a challenging “beep-to-hover” maneuver, which enabled them to safely approach the water and the ship. The “beep-to-hover” maneuver was developed by LCDR Frank Shelley—test pilot and program manager for HH-52A acquisition testing—to help pilots safely transition to an overwater hover at night and/or in instrument conditions. The HH-3F PATCH (precision approach to a coupled hover) eventually replaced the “beep-to-hover” in late 1971. Interestingly, both procedures most closely mimic the ‘early’ MATCH (manual approach to a controlled hover) in the HH-60 and HH-65 series aircraft—the PATCH and CATCH in these aircraft utilize auto-pilot and trim functions to perform a ‘hands off’ coupled approach to the water.

This “beep-to-hover” maneuver can be disorienting in the clouds at night, particularly when low over the water with little room for error. Both pilots must continuously scan and interpret the flight instruments—this is critically important—while smoothly manipulating the controls to ensure they are hitting various airspeed and altitude windows to fly the correct profile.

At the completion of this very demanding approach, the helicopter crew found itself in nearly “zero-zero” weather, but it had executed the approach with such precision that the MK-58s were located. Hovering at night, in a dense fog, and minimal visual reference with the ocean surface, the crew could barely establish visual reference with the ocean surface from a 40-foot hover or see the vessel’s lights and therefore was.

“We made what amounted to an instrument approach to the water,” Lewis explained, “Hovering just over the waves we crawled toward the ship which was about two to three miles away.”

At least that’s where a little black box on the instrument panel said the ship was. The aircrew inched forward using the helicopter Doppler hover system, the radar, and the RDF (radio direction finder, which provided a bearing to a radio signal from the ship). At about one mile out, the Steel Executive’s blip on the helicopter radar was lost in surface clutter—the mood was tense with the aircrew concerned about the combination of low visibility, closure rate, low altitude and vessel rigging obstacles. At an altitude of 40 feet in extremely limited visibility, the helicopter could literally stumble into the vessel, causing a collision that would doom everyone on board the aircraft and imperil the ship’s crew as well. Eventually, the ship’s surface search radar picked up the helicopter and guided it to her. Farmer was on a gunner’s belt leaning out the cabin door and straining to find the ship’s glow.

Lewis praised Farmer for far exceeding the scope of duties he had been trained for–hoisting the injured man off his ship and onto the hovering aircraft.

“Farmer actually guided me to the ship,” Lewis said, “I had no visual references, so I depended entirely on him. He became our aircraft’s eyes and brought us over the freighter.”

“Pucker factor” is a slang phrase used by military aviators to describe the level of stress or adrenaline response to danger or a crisis. The term refers to the tightening of the sphincter caused by extreme concern—on particularly challenging missions, the seat cushions might go missing altogether. The pucker factor had been high since the initial descent into the fog bank, however Farmer remarked, “Finally gaining a visual with the ship eased the pucker factor and transformed the aircrew’s outlook from uncertainty of success to ‘We can do this!’”

Huge spotlights pierced the fog, but all Lewis and Farmer could see was the hoist аrеа. Even under ideal weather conditions, positioning a hovering helicopter over the crowded decks of a freighter is a delicate maneuver.

“Doing it in pitch darkness while howling 25-mile-an-hour winds rock ship and aircraft alike is—in the words of the young crewmen who were there with Lewis—something else.”

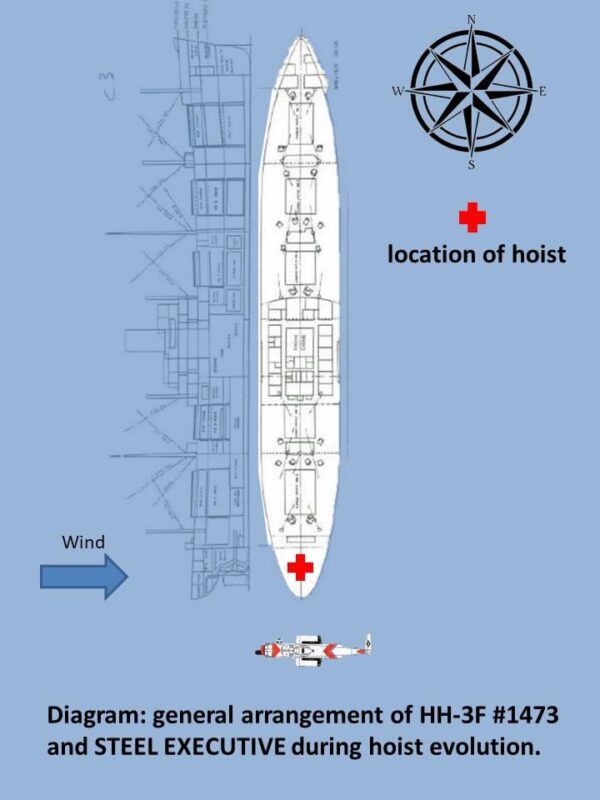

The pilot and flight mechanic were still concerned with the helicopter’s low hoisting altitude as they surveyed the vessel obstacles—the ship’s towering rigging literally disappeared in the fog above. Much of the obstacle clearance judgement and decision making fell on the flight mechanic’s shoulders as the pilot was unable to see the hoisting area behind him. The crew was convinced that a “basket with trail line” was the right technique for the situation as it would allow the helicopter to hoist from a position offset 30 to 40 feet from the ship and facilitate Lewis’ use of the Steel Executive as a hover reference. A trail line is a 105-foot piece of polypropylene line (similar to a water ski rope) with a 300-pound weak link at one end and a weight bag at the other. The weight bag end of the trail line is paid out below the helicopter and delivered to the persons in distress (usually vertically, but seasoned flight mechanics can literally ‘cast’ the weight bag to a spot). The weak link is then attached to the hoist hook and the helicopter backs away until the pilot can see the hoisting area. The persons in distress can then pull the basket to their location—creating a hypotenuse or diagonal—as opposed to a purely vertical delivery.

Farmer carefully conned the helicopter over the vessel providing voice commands to the pilot—delivering the trail line and, subsequently, the rescue basket to the stern of the Steel Executive. The semi-ambulatory patient was assisted into the basket by the ship’s crew and then hoisted aboard the helicopter. Lewis and Farmer were able to complete the hoist on the first attempt. Farmer appreciatively described Desimone’s efforts: “He spent most of his time working the radios, but he assisted me during the hoists. He was the extra set of hands getting the rescue basket into the cabin and then clearly directed the patient to the back of the cabin.” Petty Officer McCollough secured the patient for the flight, administered antibiotics, and maintained constant watch on the patient’s condition during the return flight.

Often forgotten was the job performed by Fullmer as safety pilot. He continuously scanned the system instruments to ensure the aircraft was operating normally and monitored the flight instruments to ensure obstacle clearance and safe altitude. He effectively conveyed critical information without interfering with Farmer’s conning commands.

After completing the hoist, it took a few minutes to secure the cabin—Farmer stowed the basket and secured the hoist hydraulics, then closed the cabin door and reported the cabin was secured and ready for forward flight. The pilots then executed a demanding night instrument take-off or ITO from a hover over the water. The ITO is similar to the “beep-to-hover” in terms of relying on aircraft instruments instead of visual cues, but its purpose is the opposite—to get you away from the water and into a forward flight profile at a safe airspeed and altitude. The maneuver was flawlessly executed, and the aircrew soon found themselves above the fog bank in clear skies. The helicopter returned to San Diego to deliver the patient to medical authorities. The Steel Executive crewman subsequently recovered.

Lewis earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for this mission, while Farmer earned the Air Medal. The medals were presented by Rear Adm. James Williams, commander of the Eleventh Coast Guard District, in a ceremony at Air Station San Diego on Feb. 23, 1972. Lewis also earned the American Helicopter Society (now the Vertical Flight Society) Frederick L. Feinberg Award presented to the vertical flight aircraft pilot or crew who demonstrate outstanding skills or achievement during the preceding 18 months.

In the summer of 1972, Lewis transferred to from Coast Guard Air Station San Diego to Air Station St. Petersburg, Florida, where he continued flying the HH-3F helicopter. Unfortunately, six months after the Feinberg Award presentation, on Dec. 16, 1972, HH-3F CG-1474 assigned to Air Station St. Petersburg was lost off Sarasota along with the crew of Lewis, Maj. Marvin Cleveland, USAF (Exchange pilot), AD1 Edward Nemetz, AT3 Clinton Edwards, and the four rescued crewmen from the 54-foot fishing vessel Wanda Dene (William Peek, George Dayhoss, Herbert Hardy and Paul Manley).

It was late on that Saturday when the Wanda Dene sent out a distress call. The stricken vessel was 35 miles southwest of Key West, taking on water and sinking in rough seas. Helicopter HH-3F CG-1474 was launched with its crew of four for a long-range rescue. The helicopter arrived overhead the Wanda Dene several hours later and successfully hoisted the four crewmen from the sinking vessel in challenging conditions. The 1474 then flew to Naval Air Station Key West to refuel. From there, CG-1474 with eight people aboard, departed at about 7:00 p.m. for a return flight to St. Petersburg. Normal flight operations were reported with regular radio position reports until about 8:30 p.m. Two days later, a small portion of the helicopter was found in the Gulf of Mexico south of Fort Myers. Despite a massive search, very little of the aircraft and only one body, that of one of the fishermen, was ever recovered. The cause of the crash was never determined.

On March 4, 2011, a dedication ceremony was held at Air Station Clearwater, Florida, to name an annex building in honor of the service and sacrifice displayed by Lewis. Members of the Lewis Family, including daughter Kara Lewis, wife Jackie Lewis, sister Abby Sauer, son Curt Lewis, daughter Megan Lewis, sister Joan Chaffee, and Abby’s husband, Gene Sauer attended. Here is a part of the presentation made that day: “Lt. Cmdr. Lewis was a tall, athletic Coast Guard Academy graduate who was regarded as the type of officer and pilot that others strive to become. He graduated in 1960 and went to serve his time aboard a Coast Guard cutter before attending flight school.” While the building was named to honor Lewis, the air station believed Lewis would have wanted to honor the service and sacrifice of his crew as well. Hence, the auditorium within the building was named for Maj. Cleveland, the conference room for AD1 Nemetz and the training room for AT3 Edwards.

Prior to being stationed at Air Station St. Petersburg, Lewis served at the following air stations: Miami, Kodiak, and San Diego. Lewis was known for his exceptional crew resource management and inclusion of his crew in all his flying duties. Among the pilots, he was heralded as a flight instructor and examiner who knew the aircraft better than anyone did.

Lewis is best remembered for receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross and first Frederick L. Feinberg Award honoring a Coast Guard pilot for the rescue he performed that fateful day off the coast of San Diego. On May 19, 1972, at the Sheraton-Park Hotel in Washington, D.C., Rear Adm. William Jenkins, Coast Guard Chief of Operations from Coast Guard Headquarters, presented Lewis the award outlining the case as follows:

Commander Lewis was selected for his sea rescue of an ill crewman from the merchant ship, S.S. Steel Executive, at night and under extremely hazardous weather conditions. Despite very dense fog, Lt. Cdr. Lewis took off and proceeded to the estimated position of the vessel some 220 miles south of San Diego, Calif. , and — by applying extremely skillful instrument approach procedures — was able to find the vessel with visibility reduced to an eighth of a mile and less at times, and by hovering 50 feet above the vessel, he rescued its seriously ill crewman and safely delivered the patient to medical authorities. The crewman subsequently recovered. This demonstration of courage, skill and airmanship has deservingly earned him the Frederick L. Feinberg Award.

Lt. Cmdr. Lewis presented the following acceptance speech:

“It’s indeed a deep personal honor for me to receive this award from the American Helicopter Society and from the Kaman organization. But, in a sense I really feel that it’s unfortunate that this award should be given to an individual. Without attempting to feign false modesty, I sincerely feel that this award should be shared with many others; specifically, the other three members of my crew, my service — the Coast Guard — and really, in a sense, you, the members of the American helicopter industry. I am sure there are people sitting here in the audience this evening that participated in the design, the development, and the production of the very fine Sikorsky HH-3 helicopter that was used in this rescue. In honoring the Coast Guard by my selection, I really feel that you honored a service that from the helicopters very beginning — we employed it to rescue thousands of people and saved millions of dollars of property. My rescue that is honored here this evening is really very typical of many other rescues that the Coast Guard has accomplished. And so—even though it’s my name alone that is on this award — I sincerely believe that the honor belongs to my entire crew for that evening that this rescue was accomplished and I feel also that it should be shared with the many other Coast Guard crews who accomplished many other rescues of equal ability or what may it be, but I feel I should share the honor with them.”

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors will be able to learn more about the Coast Guard’s many harrowing helicopter rescues in the Lifesavers Around the Globe wing on Deck02 of the Museum.