On Monday morning, my staff gave me an excellent wrap-up on the refugee situation in Haiti. The briefing was key to understanding the developing situation there, and was based on high-quality US Coast Guard reconnaissance photos of Haitian boat-building activity, along with background information supplied by your Intelligence Coordination Center.

GEN. Colin Powell, CJCS, November 19, 1992, letter to CMDT William Kime, USCG

![Letter: From: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Washington, D.C. 20318-0001. Dated: 19 November 1992. To: Admiral J. William Kime, USCG, Commandant, U.S. Coast Guard, 2100 Second Street, SW, Washington, D.C. 20593-0001. “Dear Bill, -- On Monday morning, my staff gave me an excellent wrap-up on the refugee situation in Haiti. The briefing was key to understanding the developing situation there, and was based on high-quality US Coast Guard reconnaissance photos of Haitian boat-building activity, along with background information supplied by your Intelligence Coordination Center. – Your people responded to our short-notice request for information and are to be commended for their professionalism, can-do attitude, and quality work. Please pass on my special thanks to all who assisted us. – Sincerely, [signature] COLIN L. POWELL, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.”](https://nationalcoastguardmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2.-Colin-Powell-letter.png)

Due to the nature of Chinese smuggling, which utilizes more unique smuggling routes and vessels, PRC interdictions have been more dependent on intelligence. Without prior intelligence information, it would be virtually impossible to accurately and efficiently interdict any maritime borne PRC aliens.

RADM Ernest Riutta, USCG, December 10, 1998, speech

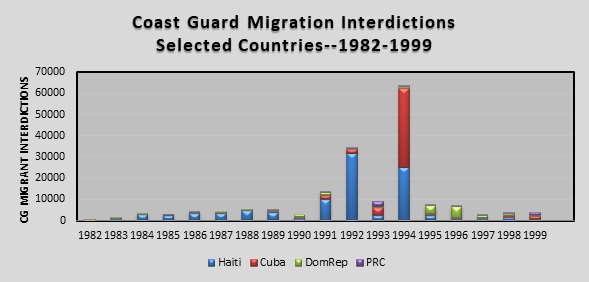

After impressive contributions to the Coast Guard and the nation during Prohibition and World War II, Coast Guard intelligence played a minimal role for an extended period. Following World War II, like much of the Coast Guard, there was a significant drawdown of intelligence capabilities. Much of what was termed “Coast Guard intelligence” from post-World War II through the early 1980s was in reality Coast Guard investigative activities and information sharing. An increase in intelligence demand developed in response to marijuana smuggling in the late 1970s and 1980s, and cocaine smuggling from the 1980s onward. Similarly, an uptick in maritime migration, starting with the Mariel boatlift in 1981, then successive mass migrations from Haiti, Cuba, and to a lesser extent Dominican Republic in the 1990s complemented by PRC migrant smuggling in the 1990s drove requirements for intelligence support.

In the early 1980s, senior leaders in the Coast Guard recognized the increasing demand and complexity of law enforcement missions (primarily narcotics interdiction) and related to that, a requirement for an intelligence program. They chartered a number of studies—notably the 1982 Special Operations Study Group (referred to as the “OZ” Study) to identify the resources and framework necessary for these operations. The output of the OZ Study can be credited with the direction for the creation of the modern Coast Guard Intelligence program. It started modest investments in capabilities and training that leveraged other agencies, while building a small cadre of intelligence personnel. It led to the establishment of the Intelligence Coordination Center (ICC) as the Coast Guard’s national-level intelligence center to interact with the Intelligence Community; Area (regional/theater) intelligence staffs to support planning and force allocation prioritization; full-time postgraduate studies in intelligence to develop its officer cadre; and dedicated professional intelligence personnel. The principal intent was to support the greatly expanding counterdrug efforts as the service—and the broader U.S. government—struggled to adapt to this ballooning threat.

The less-known story is the Coast Guard Intelligence (CGI) program’s support to migrant interdiction and mass migration response—both of which were substantial challenges in the 1980s and 1990s. Many of the intelligence capabilities and program attributes—the newly formed ICC and other intelligence staffs; intelligence professionals with strong operational backgrounds; networks across the Intelligence Community, Department of Defense, and law enforcement agencies; and the service’s lead role in specific geographic areas—despite being oriented to the counterdrug mission—also made an impact for the service in the migration arena. This ranged from tactical cueing, support to force planning and asset allocation, and also influencing national policy and prioritization.

Intelligence support to mass migration anticipation, planning, and response

While the Coast Guard has not dealt with a mass migration—uncontrolled maritime migration that threatens the U.S. national security—in many years, these events were a constant policy and operational concern in the 1980s and 1990s as the service’s intelligence capabilities were standing up. The 1980 Mariel Boatlift from Cuba preceded the initial growth of the intelligence program, yet members of the nascent program supported Coast Guard planning and participation in inter-agency discussions. The Coast Guard response to the Mariel Boatlift included the interdiction of nearly 125,000 Cubans at sea from April through September and the operational impact of virtually no Atlantic Area drug interdictions in April through June and one-third less fisheries boardings while cutter and aircraft were diverted to the Florida Straits. At a strategic level—and external to the Coast Guard– the CIA provided warning in January 1980 that “The Castro regime may again resort to large-scale emigration to reduce discontent caused by Cuba’s deteriorating economic conditions.” This was a tactic that Fidel Castro used as a safety valve to address domestic pressure. A similar State Department warning that month noted that a recurrence of the 1965 Camarioca boatlift was likely.

Within the Coast Guard, Cmdr. Jim Kenney—one of only two staff officers in the Headquarters OPINTEL Branch—was liaising with various Intelligence Community partners while also working to build a Coast Guard intelligence program. Leveraging those contacts and the efforts of the Coast Guard liaison officer at the Naval Ocean Surveillance Information Center, Lt. Steve Cornell, he used information from national resources typically leveraged for other Coast Guard missions and obtained critical indications of pending emigration from Cuba. This information was briefed to the commandant, Coast Guard operational commanders, the Pentagon, and CIA, whose director praised its value. While performed on a shoestring, the intelligence work gave a sense of what might be possible with more resources.

By the early 1990s, with a maturing ICC, and more robust Coast Guard Area and District intelligence staffs, Coast Guard Intelligence made more extensive contributions to mass migration preparation and response, arguably establishing a niche within the U.S. government for its role in that mission. Various factors—including in-country conditions, proximity to the U.S., and U.S. policy—led to Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic becoming sources of elevated illegal maritime migration to the U.S. with periodic mass migrations from Cuba and Haiti. In addition to Mariel, the U.S. experienced mass migrations from Haiti from 1991 to 92, both Cuba and Haiti in 1994, and frequent elevated spikes from the Dominican Republic. Given the service’s heavy Caribbean presence and focus, it leveraged this access and emphasis into intelligence expertise on the conditions, trends, and threats in these countries. As noted by retired captain and former ICC commanding officer Bob Haneberg, operating in and around Haiti and Cuba, and having access to migrants gave the Coast Guard insights that other intelligence community members did not have.

The 1991-92 Haitian mass migration totaled over 37,000 Coast Guard migrant interdictions involving a considerable 62 cutters and 13 air stations in the first seven months of the response. Coast Guard intelligence operations played a key role in forecasting the mass migration, determining the driving factors, and influencing national policy for the first Bush Administration and the subsequent Clinton administration. Notably, Coast Guard imagery of Haitian boat building—including a picture of a Haitian boat marked “America or bust”—and related analysis of ‘pull’ factors such as U.S. policy driving migration vice in-country conditions were briefed throughout the Intelligence Community, the Pentagon, and to the Clinton transition team resulting in a change in policy and strategic messaging.

This performance reflected maturing Coast Guard analytical prowess, and improved processes to move intelligence within the service (e.g. from District Seven imagery collectors to Atlantic Area and ICC) and readily share intelligence with the broader national security community. Notably, the D7 imagery detachment at Air Station Opa Locka in Miami had refined its procedures over several years to be responsive to multiple Coast Guard missions, several interagency customers, and regular requests from the Intelligence Community. Today, it is taken for granted, but this occurred just a few years after standing up the first Coast Guard Intelligence Center (IC) in 1984 and the work required to integrate a military service with little classified (much less sensitive compartmented information) connections with intelligence community partners. For context, the Coast Guard intelligence program totaled 220 full-time personnel in 1995, connectivity with the IC and other partners was a hodge-podge of nascent systems, and in 1994, the ICC had just moved to the National Maritime Intelligence Center to take advantage of greater connectivity.

Similarly, Coast Guard intelligence made its mark with the 1994 mass migrations from both Haiti and Cuba, totaling over 63,000 migrants. As in the past, Coast Guard Intelligence monitored in-country conditions, migrant debriefings, and the impact of U.S. policy (by now assessed as a primary factor for Haitian migration) to warn policy makers and operational commanders about pending mass migrations, and in support of United Nations (U.N.) sanctions on Haiti. This warning allowed the Coast Guard and Department of Defense time to position cutters and ships in anticipation, and shift resources from Haiti to Cuba when appropriate. The ability of Intelligence to predict both events enabled critical planning and resource allocation decisions that mitigated the potential scope of both events, likely saving many lives. This intelligence baseline and expertise was also a contributing factor in the planning and execution of the 1994-1995 Operation Uphold Democracy joint effort to remove the Haitian military regime that had overthrown President Aristide in 1991.

Intelligence support to alien migrant interdiction operations

Concurrent with monitoring threats and trends and warning about mass migrations, Coast Guard intelligence routinely supported alien migrant interdiction operations (AMIO). While mass migrations were primarily a Haiti and Cuba concern, migrant smuggling included both those countries as source and transit zones, but several others as well. Recurring migrant smuggling and illicit migration across the Caribbean, both ends of the Mexico-U.S. border, through Central America, and globally from the People’s Republic of China were regular challenges. For context, the Coast Guard interdicted thousands of illegal migrants every year during the 1980s and 1990s. Even outside of large Cuban and Haitian mass migrations, the Coast Guard interdicted over 12,000 Cubans (peak non-mass migration of 3687 in 1993), over 16,000 Dominican Republican nationals (peak of 5430 in 1996), and approximately 5,500 People’s Republic of China (PRC) nationals (peak of 2511 in 1993) in the 1990s, with well over 30,000 Haitians (again, excluding mass migrations) during the 1980s and 1990s. Coast Guard intelligence supported Coast Guard interdiction operations as well as the policy response in support of this enduring and complex mission.

PRC migration was a global threat, impacting all Coast Guard districts, differing from previously mentioned mass migration. Most PRC smuggling used coastal freighters and fishing trawlers to transport Chinese migrants across the Pacific—with landings or attempted landings in Hawaii, U.S. territories such as Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, U.S. East and West coasts, and trafficking through Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Ironically, Taiwan’s compliance with the 1991 U.N. General Assembly resolution regarding the limiting of high seas driftnetting yielded dozens of former fishing vessels now idle that were quickly brought into service by migrant smugglers. PRC migrants paid $30,000 and more to Chinese triads to be smuggled on these arduous journeys under inhumane conditions, often to work in indentured servitude for years upon reaching the U.S. Interdiction of these smuggling ventures had many challenges, including:

- The global nature of the routes

- Long distances from U.S. territory during their routes (numerous interdictions occurred hundreds of miles offshore from U.S. territories and Baja California) and complex repatriations—to including from Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands and Wake Island

- Hostile/high-risk boardings (anarchy, fires, migrants dumping most food stores overboard, hunger strikes, and opposed boardings requiring boarding teams in excess of 25 people)

- Challenging coordination with the Chinese government on validating registry and repatriation.

Intelligence was a critical factor in the successful targeting and locating of these vessels. Coast Guard Intelligence analyzed information to identify routes, assess suspect vessel characteristics, range, and profiles, and provided justification to raise the national prioritization of this threat. Intelligence support was more effective at the strategic and operational level than at the tactical level, likely reflecting the distribution of intelligence resources at that time.

Two 1993 incidents just weeks apart in May and June brought home the direct homeland security threat. These were the motor vessel Pai Sheng which smuggled nearly 200 PRC migrants to San Francisco Bay and the motor vessel Golden Venture which grounded off Queens, New York, with approximately 300 illegal migrants and crew. At the time, the Golden Venture case was the 24th smuggling vessel interdicted on its way to the U.S. since early 1992. Post-seizure analysis of the Pai Sheng yielded a treasure trove of information regarding prior events, ports of departure, and routes. Subsequent analysis identified a number of related smuggling ventures, including a five vessel ‘train’ of Chinese migrant vessels across the Pacific Ocean. Coast Guard Investigative Service and intelligence personnel worked with Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to target networks, identifying major smuggling coordination nodes in New York and Boston. Related investigative success led to the 1996 interdiction of the motor vessel Xing Da 100 miles north of Bermuda.

Nationally, Coast Guard intelligence efforts were instrumental in bringing Chinese migrant smuggling onto the radar of the intelligence community, supporting State Department initiatives, and helping to raise its importance to the Clinton administration. Coast Guard Intelligence analysts were key contributors to national-level intelligence collection and analytical efforts. The ICC chaired an interagency working group that also included State Department, Naval Intelligence, Immigration and Naturalization Service. It participated in interagency teams briefing U.S. embassy personnel in South and Central America on smuggling methods and trends. It also coordinated analysis with international partners that were combatting this threat. Coast Guard expertise and leadership were demonstrated in the roles assigned to the Coast Guard, the intelligence community, and agencies supporting interdiction efforts listed in the 1993 Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-9 directing the governmental response to “preempt, interdict, and deter” alien smuggling.

Offshoots of Intelligence program development

The principal reason for creating the modern Coast Guard intelligence program—and its early focus—was the growing counterdrug effort of the 1980s; however, the modestly resourced program made its impact in other missions like migrant interdiction. The program’s development over the next two decades had the corollary effect of helping the service’s broader transformation into a more national security-centric and -relevant entity. The intelligence program leveraged Coast Guard operations (and thus, access) in unique locations and work with intelligence community partners on intelligence collection and assessments. Its expertise in specific areas related to Caribbean and Latin American issues allowed it to establish a niche within the national security community. Additionally, its contributions to and early adoption of classified computer networks, such as Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communication System (JWICS) and Secret Internet Protocol Router Network (SIPRNET), led broader Coast Guard use of both systems and brought relevance and integration with key national security entities.

In the 1990s, the Coast Guard participated in multiple high-visibility national security issues. Among these included mass migrations, Operation Uphold Democracy in response to the 1991 Haitian coup, and PRC migrant smuggling. These incidents resulted in an elevation of the service’s national security standing and increased resources for intelligence program maturation. This not only enhanced the Coast Guard’s reputation and relevance, but it helped the traditionally resource-starved service grow. For example, due to the frustration of JWICS (top secret system) program owner, DIA Chief Lieutenant General James Clapper, with the lack of classified communication with the Coast Guard during Operation Uphold Democracy, the service was allocated three of the initial 31 JWICS sites across the entire U.S. government, an item lined out of a previous Coast Guard budget request. This was a significant development that helped the Coast Guard engage in conversations and coordination with multiple national security partners. Over the course of the 1990s, the Coast Guard began to influence national policy and prioritization, demonstrating the service “punching above its weight class.” Thus, a small intelligence program nestled within a small service located in the Department of Transportation increasingly operated in the broader interagency environment, bringing a version of ‘jointness’ during a period when Congress was directing such integration within the Department of Defense.

While not on the scale of the program’s counterdrug support, the intelligence support to migrant interdiction and mass migration response was crucial in the program’s—and the service’s—development. It helped the program’s growing influence and credibility with operational commanders and key decision makers. Similarly, it helped enhance the Service’s interagency reputation and impact. Relatedly, supporting and improving the Coast Guard’s migrant interdiction operations was a specific factor in Congressional intent to bring the Coast Guard into the Intelligence Community. That interest and the later 9/11 terrorist attacks provided the conditions for formal community membership and significant program growth in the early 21st century.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The history of Coast Guard intelligence, from its earliest days to its expansions in the modern era will be told in both the Enforcers on the Sea, and Defenders of our Nation wings on Deck03 of the Museum.