The cause of the 1980 refugee exodus from Cuba, also known as the Mariel Boatlift, was deeply rooted in that nation’s internal affairs. The first signs that those seeking to leave Cuba in water-borne escape to the United States occurred during the second week in April. On April 11, a Miami radio station began broadcasting that Cuban Americans were to gather with their boats (those over 20 feet). The stated purpose was to sail to the limits of Cuban waters, 90 nautical miles [nm] from Florida, to bring pressure through media coverage on Castro’s immigration policies. Food and water were to be passed to the Cuban Border Guard for relay to those in the Peruvian Embassy.

Coast Guard Adm. Benedict Stabile was responsible for executing the service’s responsibilities in this area. In addition to information gathering, Seventh Coast Guard District initially responded to public inquiries by pointing out the risk involved in crossing the Gull Stream in a small craft. Reportedly, 60 to 80 craft were going to take part in this peaceful protest. On April 14, eight craft were trailered to Key West and another arrived by water. Due to bad weather, only one craft began the voyage, and it turned back.

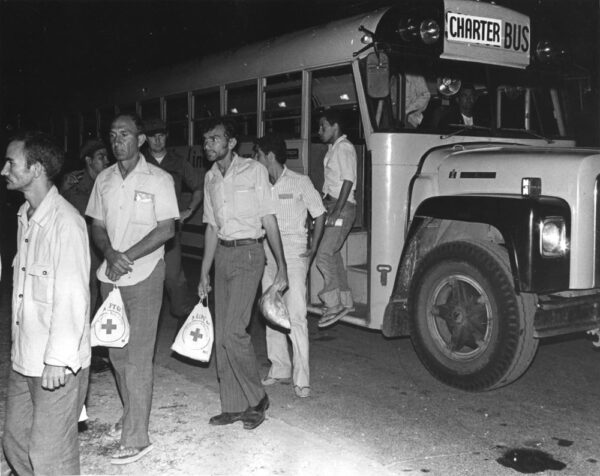

On the morning of April 21, Radio Havana announced that two U.S. small craft had been permitted to pick-up refugees, who were related to individuals on board the craft, from those housed at the Peruvian Embassy. The broadcast stated that other boats would be allowed to enter Cuban waters for the same purpose. Reportedly, 25 to 50 craft were waiting off Havana for permission to enter. That same afternoon, one fishing vessel and three small craft returned to Florida with refugees on board. The fishing vessel broke down two nautical miles from the Key West main channel sea buoy and had to be towed to Coast Guard Group Key West by a cutter. Contrary to the Radio Havana’s statement, family members of those on board the craft were not permitted to leave Cuba. Cuban officials reportedly told the operators that the requested individuals had not yet been processed and that their craft would have to carry refugees ready to leave.

On April 22, refugees arriving in Florida, stated in radio interviews that the Cuban government had opened its coast for anyone to leave, provided they had a permit to do so. On that afternoon, a Coast Guard HC-131 from Air Station Miami began surveillance patrols of the area south of Key West; a second flight was flown that day, and the twice daily patrol flights became routine. Also, on the April 22, the Seventh Coast Guard District informed Coast Guard Headquarters that an adequate search and rescue posture was being maintained in the transit area.

Soon thereafter, a fishing vessel and two private craft docked at Key West, carrying more than 280 refugees. Another 68 refugees arrived at Miami on board another fishing vessel. The Coast Guard air patrol sighted approximately 50 craft south of Key West and a like number between Miami and Fowey Rocks, all southbound. Radio traffic indicated their destination to be Cuba. Three of the southbound small craft broke down and were towed to Key West by cutters. One fishing vessel was sighted northbound, carrying approximately 60 refugees. Additional small craft were anchored along the reef line. Late that evening, an Urgent Marine Broadcast warned that transporting aliens to the United States was illegal and violators may be arrested and their vessels seized; this was reissued the following day. The public affairs officer of the Seventh Coast Guard District appeared on local TV evening news stating the Coast Guard’s role and again, on April 24.

Beginning on April 22, Coast Guard Headquarters officials met with representatives of agencies on the National Security Council, which included personnel from the Department of State, Justice and Treasury at the White House, to review U.S. policy. The tempo of the exodus increased. By April 24, an estimated 11 vessels had safely crossed to Cuba and had returned with over 700 refugees, disembarking them at Key West or Miami. The refugees had embarked, at Mariel, with at least one pick-up having been made at Havana.

Locally, the Coast Guard responded to distress calls on a case-by-case basis. Within a 21-hour period, Group Key West assisted 16 craft. Cutters Acushnet, Dauntless, and Dependable (the latter with a HH-52 helicopter embarked) patrolled the general area. Cutters Dallas and Ingham were at Guantanamo and were available on short notice. The Coast Guard’s Miami Operation Center received hundreds of inquiries from would-be refugee transporters. These boaters were told to clear their departure with Customs; not to violate their vessel’s documentation limits for carrying passengers; to provide a personal flotation device for each person to be carried; and to notify the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) immediately upon returning with aliens. These boaters were also encouraged to file a float plan. The same instructions were broadcast on marine radio.

The size of the refugee flotilla was staggering. Trailered boats were lined up 50 to 100 deep at Key West waiting their turn to be launched. This went on for between 36 to 48 hours; residents could hear the activity around the clock. Hundreds of trailers were scattered throughout Key West. One thousand craft were observed southbound on the afternoon of the 24th. For the most part, these were Cuban Americans who owned their own boat, typically boats between 20 and 40 feet long and well equipped for local pleasure boating. Reportedly, the tanks in numerous craft had inadequate fuel capacity and the vessels were carrying additional fuel in portable containers. This first wave resulted in the transit of 1,000 to 1,200 boats to Mariel in relatively short order.

By Friday, April 25, Cuban Americans who did not own boats drove to Key West in massive numbers attempting to buy a boat and hire a captain. This was the second wave. Those who were successful sailed on Friday in groups of ten and 20. Many were totally inexperienced and had no appreciation of the risk they were taking. At that time, Group Key West had the Cape York, Cape Shoalwater, Point Thatcher, and two 41-footers; they were deluged with assistance calls due to routine breakdowns. Group Key West had a waiting list of between 10 and 30 boats, which had suffered mechanical failure and needed assistance. Group Key West was conducting a 24-hour operation just towing in people. Also, on Friday, some flotilla boats began to return to Florida. The high number of departures and the significantly lower number of returnees indicated a probable bottleneck at Mariel. Countless search-and-rescue [SAR] calls were answered on this day, 12 being serious cases requiring medical evacuation or assisting sinking craft.

The exodus fleet had become a steady stream involving hundreds of craft. They ranged in size from 18 to 90 feet, and at least 20 could be seen from the patrolling Coast Guard aircraft at any given moment. The broadcast warnings of potential monetary penalties, seizures, and arrests were acknowledged by many departees, who continued on their way. On Friday and throughout the next day, many of the inexperienced boats broke down and reacted in a panicked manner. Group Key West was totally absorbed in towing in disabled boats.

The Seventh Coast Guard District issued an operations order identifying “enemy forces” as “(1) adverse weather and strong currents (2) unworthy and overloaded boats (3) persons intent on violating U.S. law.” The mission was “to provide maximum protection for refugee vessels . . . transmitting between Florida and Cuba for an extended period of time.” This operational order was amended on May 3 and May 20 to adjust to changing circumstances. On Sunday, April 27, the weather in Key West went to hell—a “mini-hurricane” passed through. Winds shutdown the Naval Air Station—which typically occurs when they go above 60 knots. The Group had 22 “maydays,” serious cases involving danger to life, in about five minutes. It was instantaneous disaster. During the next two to three hours, people were literally backed up in the water. Fortunately, the weather front was short-lived, and the helicopters were able to join the cutters in rescue operations within an hour after the storm started.

The large cutters were also inundated with SAR calls. The volume of cases became so heavy that accurate records could not be kept. At one time, Cutter Ingham had five vessels in tow and an estimated 14 persons on board, taken from four or five swamped boats. These had to be left adrift. Cutter Diligence had six craft in tow, was escorting two others, and had 23 persons on board from an awashed vessel. By April 29, two bodies were found in a capsized vessel, 18 miles east of Trumph Reef. Numerous abandoned and capsized craft were observed.

This bad weather only temporarily reduced the number of sailings. At that time, Coast Guard Auxiliary Division 13 took over the day-to-day SAR cases of Group Key West, such as assisting disabled fishing and charter boats. By April 29, the exodus was once again in full operation. Following this storm, many of the Cuban Americans, who did not own boats, were paying large sums to small commercial craft, such as shrimpers, to bring back relatives. Reportedly, up to $1,000 a head was being charged. Over 1,700 vessels were reported to be in Mariel by the Cuban Government, 19 were sighted northbound plus 67 southbound, 400 craft were awaiting to be launched at Key West, and a like number had been launched in the previous 24 hours. Conditions in Mariel were described as terrible. Exorbitant prices were being charged for supplies. Cuban authorities extended credit to some boaters, but they were not allowed to depart until the money had been wired to Cuba. Cutter Ingham reported that vessels were returning without refugees and Diligence reported that radio traffic indicated that the Cuban Government was requesting vessels to come back in 30 to 60 days, as they would only be able to process those refugees already in progress. These bad conditions and projected delays were causing many boats to return empty. Of the 188 boats sailing northbound on May 1, 84 of them were not carrying refugees.

On April 29, the Coast Guard’s Seventh District Commander sent a telegram to the Cuban Border Guard asking, in the name of safety, to be advised of the names of the vessels departing Cuba and the approximate number of people on board. This information would have permitted the Coast Guard to keep a semblance of order. No immediate response was received. Unconfirmed reports indicated that the Border Guard would escort vessels to the midway between Cuba and Florida, a traditional exchange point. Cutter Ingham sighted two Cuban Border Guard vessels escorting eight boats on a northerly course. Group Key West confirmed that the escort proceeded to within 13 miles of Key West. On April 30, a telex message was sent by the Commander of the Seventh District, inquiring if the Cubans intended to continue the escort service, and if so, offering to establish a hand-off procedure. The Cuban Border Guard agreed to a mid-point escorting service, in the May 1 message, which accused Dallas of territorial violation. They stated that it was impossible to provide the names of vessels and numbers on board due to the volume. The Seventh District began to work on a “hand-off” plan. However, this arrangement did not materialize and would not have alleviated the need to have a cutter located close to Cuba to provide a rescue presence for southbound vessels.

Also, on April 29, the Coast Guard began providing daily forecasts of arrivals to Immigration and Naturalization Service [INS], Customs, Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], and volunteer agencies based on aerial reconnaissance to facilitate orderly processing. Cutters were assigned “sectors,” roughly 800 square nautical miles. These were adjusted as need arose. Key West Naval Air Station, Boca Chica, was now opened on a 24-hour basis to Coast Guard helicopter operations. Admiral Stabile requested the media to provide additional weather details to boaters; they fully complied as a public service. On April 29, the Seventh Coast Guard District cited the first vessel for “grossly unsafe” operations. The group commander in Key West reported evidence of an increasingly negative reaction to law enforcement efforts the Cuban Americans.

During a surveillance flight on April 30, a Coast Guard HC-31 aircraft was intercepted in the Havana Flight Information Region by two Cuban MiG fighters, approximately 20 miles off Cuba. The first pass appeared to be for identification and not harassing or provocation. The MiGs returned and circled the aircraft until it turned north, at which time they turned toward Cuba. On Wednesday night, April 30, Dallas observed the 502-foot Greek merchantman Euro Champion northbound in the Straits of Florida with a Cuban patrol boat in pursuit. Radio communications indicated that the vessel had Cuban refugees on board and was possibly hijacked. Later, it was learned that when the pursuing patrol boats had intercepted Euro Champion, they had identified themselves as “U.S. Coast Guard,” and directed the ship to stop for boarding. The deception did not work. The patrol craft then fired automatic weapons in the air. When the Dallas arrived on the scene; Euro Champion headed for her.

Then the Cuban craft visible from Dallas fired a flare and retired southward. The following day, Euro Champion was found hard aground near Tennessee Reef. Cutter Vigorous boarded and inspected papers. There had been no hijacking. Three refugees were on board. One requested to be removed and was transferred to the INS and the others chose to remain on board until the ship reached its next port of call, New Orleans.

On May 1, the Cuban Border Guard accused cutter Dallas of approaching within nine miles of the Cuban coast. They protested and asked that future violation be avoided. The Coast Guard advised the Border Guard that Dallas’ navigational plot indicated that at no time had the cutter come closer than 28 miles of the Cuban coast. The Coast Guard intended to routinely patrol up to 12 miles of the Cuban Coast, and if necessary, would respond to SAR cases to within three miles of shore.

Also on this day, the Joint Chiefs of Staff tasked the commander-in-chief, Atlantic, to augment Coast Guard units in the Straits in Florida for search and rescue operations. USS Saipan an amphibious assault ship carrying 17 helicopters, and USS Boulder, a tank landing ship, were dispatched with Rear Adm. Warren Hamm, Navy, commander Amphibious Group II, embarked. A Coast Guard liaison officer flew out and boarded Saipan off West Palm Beach as the ships were sailing south. Thus, all five services were represented on board Saipan. They arrived on the scene five days after leaving Norfolk.

The weather on May 1 was more severe than forecasted. A line of thunderstorms passed between Key West and Cuba; gusts were up to 60 knots and there were 12-foot seas. The Coast Guard advised the Cuban Border Guard of the severe weather and requested that they tell boaters not to depart until the storms passed. The Cubans responded that they had taken appropriate measures and expressed thanks for the information. By May 3, the volume of boat traffic fell off, probably due to the embarkation delays in Cuba reported by the media. However, this respite lasted only one day.

On May 3, the Cuban rescue boat Tuma, a 165-foot converted side trawler, radioed Dallas and arranged a rendezvous to transfer a tow. Tuma was towing a Florida registered, 22-foot pleasure craft with 15 persons on board, 14 of whom were refugees. Previously, the Cuban rescue boats had been taking disabled craft back to Mariel.

While attempting to recover her helicopter on May 3, Dallas was circled for 10 minutes at 80 feet high by a U.S. registered civilian helicopter. This aircraft failed to answer calls on the emergency frequency and was preventing the Coast Guard helicopter from landing. The incident was reported to the Federal Aviation Administration [FAA]. On May 7, the FAA issued a “Notice to Airmen” delineating an area, which aircraft should avoid so as not to interfere with patrolling Coast Guard cutters and naval ships.

On May 5, Saipan and Boulder arrived on station. Also, their surveillance patrols were augmented by naval aircraft from Jacksonville. Five patrols were planned for each day, four Coast Guard and one Navy. Three on-scene commands were established under operational control of the commander of the Seventh Coast Guard District. The Coast Guard’s commanding officer of Group Key West was responsible for the tidal area, out to 10 to 15 miles off the Keys. He controlled the Coast Guard patrol boats, Coast Guard helicopters at Key West, the Auxiliary, and other inshore assets. Hamm controlled the middle waters with the two large amphibious ships and embarked aviation squadrons. The waters closest to Cuba were the responsibilities of the Coast Guard squadron commander, who was the commanding officer of Dallas. His force was two high-endurance cutters and two to four medium-endurance cutters.

Also on the May 5, cutter Cape Gull intercepted and escorted to Key West the ocean-going tug Dr. Daniels with 449 persons on board. The vessel had been chartered for $70,000 by Cuban Americans to transport relatives. Apparently, the vessel was ordered by a Cuban patrol boat to embark those refugees immediately available and depart. Dr. Daniels had lifesaving equipment on board for only about a third of the people. The vessel was seized by Customs in Key West. Cutter Ingham reported that she was informed by a pleasure craft that the 150-foot America was in Mariel boarding approximately 900 refugees.

Coast Guard and naval units were alerted to be on the lookout for grossly overloaded craft. Commandant Hayes held a press conference on the May 7.

“Cuba is party to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea [SOLAS); yet thousands of refugees in the current “freedom flotilla” are encouraged to leave that country in overcrowded, unsafe vessels. This is totally inconsistent with Cuba’s treaty obligations under SOLAS and other international agreements.”

The commandant pointed out that Cuba’s current attitude toward the exodus was “courting disaster” and could result in a marine tragedy involving hundreds of lives. The Dr. Daniel case was used to illustrate the point. Admiral Hayes appealed to Cuba to act as a responsible member of the international community. The Commandant and Admiral Stabile hoped to make the Cuban government more accountable by publicizing its responsibilities.

Obtaining accurate information as to the number of exodus craft waiting to carry refugees from Mariel was a continuing problem. On May 7, the Seventh District estimated that 508 vessels remained in Cuba. Returning refugees said that between 1,500 and 2,000 U.S. boats were in Mariel and that 75,000 to 100,000 people were waiting transportation at Mariel. An accurate count was complicated by numerous factors. First, Mariel was an important Cuban port, generally crowded with Cuban national boats. Second, it was a big harbor with many indentations. Third, many small, high-speed boats were apparently being exchanged for the freedom of some refugees. This was not learned until sometime later. Fourth, the Coast Guard had to rely on counts by ever-changing third parties, who were generally viewing the harbor from a height of ten feet above the water. On the following day, the Seventh District revised its estimate to 1,500 vessels remaining in Cuba.

Also on Wednesday, May 7, Group Key West reported that the 72-foot vessel Dawn II was planning to sail to Mariel. The vessel was reported to have split seams, holes at the water line and had a history of being assisted by the Coast Guard for electrical fires. Based on the commander’s recommendation, Stabile authorized terminating the use of Dawn II as being manifestly unsafe for the intended voyage. Also on Wednesday, the Stabile visited Saipan, cutter Dallas and Group Key West to review operational procedures.

On Thursday, May 8, the 110-foot America radioed to the Coast Guard that she had been forced to depart Mariel with refugees on board. When four miles off that port, personnel from two Cuban patrol boats boarded America and forced her to return. Saturday evening, cutter Dauntless located a catamaran America outbound from Mariel. Accompanying her were numerous fishing and pleasure craft. Cutters Dauntless and Vigorous removed refugees to eliminate overloading and escorted all 31 craft to Key West. Cutter Dauntless received reports that at least five grossly overloaded, large boats had sailed from Mariel between 0300 and 0600 with 500 persons on board each. Later that day, Cutter Valiant located the 68-foot fishing vessel Capt Preston with 308 refugees and a crew of 28 on board. Late that evening, she along with Big Baby (66-foot, 185 on board) and Crazy Horse (77-foot, 318 on board), arrived in Key West. These vessels were detained pending investigation. No information was received on the other reported overloaded vessels.

During the day, cutter Dauntless picked up 131 persons from six overloaded boats, two of which were disabled. These persons were transferred to Saipan. Saipan and Boulder, using their landing craft as shuttles, removed people from overloaded and disabled boats. These refugees were then transferred to Key West by helicopter, landing craft or Coast Guard cutters.

On May 10, a strategy meeting was held to recommend future actions. Those present included the commandant, Stabile, and top government officials representing concerned agencies. Beginning this date, numerous vessels were either seized or detained. These fell into two categories. Vessels, mainly pleasure craft, which had gross safety violations, were the first. These craft were escorted into port and were not permitted to leave until the violations were corrected. Vessels, generally large commercial types, which had returned to the United States with large numbers of non-visaed aliens on board, were the second. These vessels were detained, pending the operator’s ability to produce collateral to cover the probable fine for transporting illegal aliens into the U.S. The number of vessels which had been acted against prior to May 10 had been minimal.

Also, beginning on May 10, it was not unusual to have half a dozen or more vessels terminated or detained on a single day. On May 11, Cuba advised by Telex that the 24-foot, U.S. craft Nacy with two persons on board was reported disabled and adrift about 10 miles northeast of Mariel. The Cubans requested that, if sighted U.S. patrol units should assist the craft. This was the first attempted cooperation by the Cubans since the tow hand-off on May 4. The Cubans stated an objection to an American patrol craft approaching within 12 miles to assist Nacy.

On May 12 the cutter Courageous was diverted from the Cuban refugee operation at the request of the American Embassy in Nassau to search for survivors from the Bahamian patrol boat Flamingo. Flamingo was sunk by a Cuban MiG aircraft on Saturday, May 10, near Santo Domingo Cay. Also on May 12, the commander of the Third Coast Guard District [Price held the dual command position of commander of Atlantic Area and commander of the Third Coast Guard District] terminated the voyage of the 50-foot vessel Barbara, a converted Navy liberty launch. The 10 Cuban Americans on board stated that they were paying the operators $100 per day to pick up relatives in Mariel, having been towed by the Coast Guard to the Shark River Station near Manasquan, New Jersey, in a disabled condition. The vessel was unregistered, undocumented, uninspected, and the operator was unlicensed. In addition, multiple physical discrepancies were found, leading to the manifestly unsafe determination.

The number of vessels remaining in Cuba had declined to an estimated 1,000 by May 13; 117 were observed northbound on that day. Cutter Dallas saw 11 fishing trawlers and 11 smaller craft departing Mariel together. Some began to leak, some had medical problems, and one caught fire. Two people were evacuated by Dallas’s helicopter for medical treatment. Later, Dallas found the 24-foot Sea Hunter, which had been disabled and adrift for seven days. The boat and two-man crew were taken to Key West. Cutter Diligence removed 28 people from a craft just before it sank. She escorted a convoy of 23 vessels with an estimated 1,500 people on board to Key West.

On May 14, the president implemented a five-point program to end Cuba’s inhumane actions and to bring safety and order to a process, which continued to threaten lives. The third point urged boats already in Mariel to sail without refugees and prohibited new trips from being undertaken. To implement the President’s program, 15 boarding teams, created at Coast Guard suggestion, were formed to inspect each returning vessel. A team was composed of a Coast Guard marine investigating officer (MSD), a Coast Guard boating safety detachment (BOSDET) member, a Customs person, and an INS representative. The Customs representative and MSD officer would interview the master and crew. The BOSDET person would conduct a safety boarding, and the INS officer would remove the refugees. The team would recommend what legal action should be taken against a returning boat to the U.S. Attorneys.

Reports from the Homestead Marine Operator indicated that at least two vessels in Mariel had heard President Carter’s message over commercial radio. Radio communications between cutter Dallas and a vessel in Mariel indicated that Cuban authorities were not permitting boats to depart unless they first took refugees on board. This tended to be confirmed by two other boats via the Marine Operator, who stated they had seen several vessels being escorted back to Mariel by Cuban patrol craft, because they had departed without refugees. Additionally, many of the boats departing Mariel on May 13 were found to be grossly overloaded and hundreds of people had to be removed enroute by cutters and helicopters. Cutter Dallas had 260 refugees on board and six vessels in tow, carrying 57 more people. To implement the Five Point Program established by President Carter on the 13, additional resources were identified throughout the Coast Guard to augment forces in the Florida Keys. In addition, urgent marine Broadcasts were made by the Coast Guard in both English and Spanish, advising boaters underway to return to the U.S. without delay.

By May 15, an estimated 564 vessels remained in Cuba, although some reports placed the number at over 1,000. All 268 vessels sighted northbound had refugees on board. An HH-52 helicopter established radio communications with vessels in Mariel. They stated that the President’s plan had been heard on the radio and some vessels wanted to comply and return to Florida immediately without refugees. But two Cuban boats were preventing them from departing. Cutter Dallas received conflicting radio reports that, if agreeable to all parties, vessels could leave without refugees. The Coast Guard was notified by the master of the fishing vessel Mr. Gardner that he wanted to leave Mariel without refugees, but that the passengers who chartered the vessel threatened the lives of the crew. However, the fact that all northbound vessels contained refugees supported the reports that Cuban authorities were not permitting the craft in Mariel to comply with the president’s directive.

Coast Guard units operating in the Straits of Florida indicated that there was heavy radio traffic on channel 16 VHF FM, making communications difficult, but no indication of intentional jamming of urgent marine broadcast, as reported by the news media. The broadcast concerning the president’s program was continuing to be made.

During the following weeks, additional resources were ordered to the Straits of Florida to augment and relieve the refugee task force, now executing the President’s Five Point Program.

The number of craft estimated to be in Mariel continued to decline. By Saturday, May 17, the estimate was 341. The Coast Guard continued to transmit the Urgent Marine Broadcast stating the government’s position. Of the 91 vessels sighted northbound, 87 had refugees on board. Six units were sighted southbound on Saturday. Two could not be intercepted due to darkness and the others escaped because all Coast Guard units in the vicinity were engaged in the Olo Yumi rescue.

On the morning of May 17, the pleasure craft Olo Yumi with 52 persons sank when the people on board panicked, ran to the stern, and caused water to come over the transom. The helicopter on patrol from cutter Courageous sighted the people in the water and began rescue operations. The cutter, a few miles from the disaster, broadcasted the emergency. Arriving, Courageous launched her boats, lowered cargo nets, and put swimmers in the water. She along with Coast Guard helicopters rescued 38 and recovered 10 bodies. These refugees had been among those housed in the Peruvian Embassy. One survivor, a 15-year-old girl, lost both parents, both sisters, and a grandparent. The boat had been grossly overloaded.

The Coast Guard received information that refugees were being dropped off in the Naples-Sanibel area by boats less than 25 feet. This indicated a possible at sea transfer from larger vessels. The INS was notified; patrol vessels were ordered to watch for vessels deviating from the Mariel—Key West Corridor. and night searches, using aircraft equipped with high illumination search lights, were begun.

By Sunday, May 18, only an estimated 177 vessels remained in Mariel. Conditions for the refugees and boaters continually deteriorated at Mariel. Returnees were now stating that a concentration camp atmosphere existed. The commander of the Seventh Coast Guard District pointed out in news releases the overloaded condition of most boats. The master of the Fishing Vessel Atlantis claimed he was forced at gunpoint to board 354 refugees, even though he had only 80 life jackets on board. Dallas received a message from Atlantis stating she was taking on water. Upon visual contact, Dallas could see that Atlantis was in an advanced state of disrepair. Dallas maneuvered to provide a lee in the six-foot seas. The cutter’s presence calmed the people on board, Dallas escorted Atlantis to Key West. Sunshine, a 35-foot pleasure craft, had also been forcibly overloaded. Cutter Point Huron investigating a mayday found three persons died and 27 others suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning. Only the operator and crew, who were above deck, were unaffected. The Coast Guard Marine Safety Detachment, Key West, indicated that 90 percent of returning vessels were either overloaded or carrying maximum loads. To date, there were 24 known losses of life, most due to Cuban policies or indifference. Admiral Stabile voiced the concern that with fewer vessels entering Mariel, the Cuban government might be tempted to overload the remaining vessels to even a greater degree. The admiral urged the consideration of additional initiative at the National and International levels to restrain the Cubans from such practices.

On May 19, the Seventh Coast Guard District revised the number of craft remaining in Mariel to 408. This was believed to be accurate to within +/-50, the first time an accurate projection was given. Of the 247 vessels sighted northbound, all but six carried refugees. Cutter Dallas reported that numerous Cuban government vessels remained south of latitude 24 degrees north. Some were harassing boaters while others were helping them; however, no serious incidents occurred. Many of the refugee boats, heading northward, became disabled. Dallas evacuated nine people from the 24-foot Mandy: the boat had to be left adrift, partially filled with water. Cutter Courageous had several boats in tow and approximately 200 refugees were on board.

By Tuesday, May 20, the movement southbound was nil. Late in the morning three small craft were sighted heading toward Mariel, but they were too close to the buffer zone to intercepted. Another craft was turned back by Cutter Valiant. An estimated 400 vessels remained in Mariel.

Approximately 50 boats sailed for the U.S. on May 21. The 53-foot Missy had to be taken alongside Dallas because of extensive rotting. The vessel then crumbled against the cutter’s pneumatic fender. Dallas removed 120 people with the assistance of a naval landing craft and took Missy in tow.

Reports to cutter Courageous indicated that boats lying in Mariel were beginning to organize themselves. they began to passively resist Cuban authorities from boarding. Cuban authorities appeared to have been instructed to stop harassing the boaters.

On May 22, an estimated 200 vessels remained in Mariel with 50 sailing for Florida during the day. Two southbound vessels were intercepted by cutter Vigorous and escorted to Key West. One, Cathy of California was seized and the operator arrested for violation of the Cuban Assets Control Regulation and 8 USC 1324A.

On Friday, May 23, cutters Valiant and Courageous intercepted Fishing Vessel Star. The operator stated that he was meeting the pleasure craft Mary 15 miles off Cuba to escort her back to Florida. Approximately 16 miles off Cuba, Star unsuccessfully tried to evade Courageous. She was seized and returned to Key West. Also on Friday, the amphibian assault ship USS Saipan was relieved by USS Ponce. Thus, the four Coast Guard helicopters stationed at the Key West Naval Air Station became the principal helicopter resource available.

Saturday night, May 24, at 9:13 p.m., while patrolling alone north of Mariel Bay, cutter Acushnet was approached by three Cuban gunboats, which, according to Acushnet crewman Petty Officer 1st Class Bob Dyche, a storekeeper, “were circling us, herding us in effect, maneuvering in such a way as to force us into a violation of their territorial waters. They were. . .often within 60 feet of us, severely limiting maneuverability: we could not break free without hitting at least one of them.” The gunboats switched on their searchlights into the cutter’s bridge. This could cause the loss of night adaptation.

At 10:15 p.m., the cutters stopped, at which time the Cuban patrol craft departed to the south. On Sunday, May 25, an estimated 107 vessels remained in Mariel; 116 returning to the United States during the day.

Late that night, cutter Dallas reported large groups of vessels departing Mariel. A similar weather warning was sent on the May 26. Northbound traffic continued during the next few days and many of the craft required help. The use of pleasure craft and small commercial vessels to transport refugees was winding down.

A new problem arose—the possible use of foreign flag vessels to transport refugees on May 29. Red Diamond, a large ship of unknown registry, was reportedly loading refugees in Mariel. A second ship, the 276-foot Panamanian Rio Indio was reportedly enroute to Mariel for the same

purpose. Panama authorized the Coast Guard to board Rio Indio, if found on the high seas, and inspect her for safety under the Safety of Life at Sea Convention. In addition, Panama authorized the Coast Guard to advise the master that if he took refugees from Cuba, he would be in violation of Panamanian law and his certificate would be revoked. Rio Indio was reportedly heaved-to south of Cabo San Antonio; Cutter Courageous was dispatched to locate the vessel.

Courageous found and boarded Rio Indio on Friday evening, May 31. The master was told that if he transported Cuban refugees, he would be violating Panamanian law. SOLAS violations were found, putting the vessel’s registration in jeopardy. At first, the master indicated that he would go to Mobile, Alabama. However, the captain was coerced by Cuban Americans, who were listed on the manifest, to go to Mariel. The commanding officer of Courageous believed that the only way to prevent Rio Indio from proceeding to Mariel would be by use of force. Stabile strongly recommended against this, and Courageous’ commanding officer withdrew the boarding party. Courageous maintained surveillance as Rio Indio proceeded along the Cuban shoreline. She entered Mariel at 2 a.m. Sunday, on June 1. Shortly before it entered the port, Panama authorized the U.S. to reboard Rio Indio to investigate possible violations of Panamanian law. Courageous had directed Rio Indio to proceed outside 12 nautical mile limits for boarding, but she had refused to acknowledge the message. Delaying Rio Indio allowed time to contact the Panamanian government, which prohibited the use of Panamanian-flagged vessels for transporting refugees.

The Coast Guard Auxiliary, a volunteer force of dedicated citizens, was asked to patrol the reef line from the northern end of the keys to Key West. Known as “Operation Keying,” Auxiliary boats were stationed at 13 sites by June 1 to provide on-site SAR capability and to give the service a high presence profile. Auxiliary boats, ranging from 18 to 36 feet, came from as far away as Atlanta, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, thus, many were operating in strange and treacherous waters. This patrol lasted until June 15.

On June 2, Red Diamond, since learned to be Panamanian [the Panamanian government cancelled the registry of Red Diamond and Rio Indio] sailed from Mariel with 731 refugees, including 35 infants on board.

On Tuesday, June 3, the commander of Coast Guard Southeast Squadron reported that more than half of the vessels departing Mariel needed assistance. Over 1,000 vessels had been aided since the beginning of the exodus. The 118-foot Panamanian vessel Return to Paradise returned to the U.S. without refugees on this day. The master said the Cubans would not permit refugees to board. Cutter Chilula learned that now stateless Rio Indio sailed from Mariel without refugees as well. These cases were evidence that the Cuban government was honoring the request of Panama not to load refugees on board Panamanian registered vessels. However, vessels were still being overloaded far more than safety standards. The 38-foot Bahamian Veronica Express with 222 persons on board, while towing the cabin cruiser Once More with 69 on board, radioed that she was taking on water. Cutter Acushnet removed 146 from the Veronica Express and took over the tow. Later, Cutter Cape York removed the refugees from Once More. During the next five days, the few boats remaining in Mariel trickled northward but no significant SAR cases took place.

Cutter Ingham, now the on-scene Commander of Coast Guard forces, took a 20-foot boat with one person on board in tow on June 8. The tow and man were passed to USS Dominant for transportation to Key West. A half-hour later, a Cuban gunboat approached to within 50 feet of Dominant and demanded that the Cuban national be turned over to them. The Cubans stated that the man had stolen the boat, left Cuba without permission, and was wanted for murder. Dominant refused to return the individual, stating that the man had been picked up in international waters and would be turned over the other authorities in Key West. The Cuban gunboat departed to the south. On June 9, the Seventh Coast Guard District authorized the release of naval resources, this occurred at 4 p.m. the following day. Over-flight support by Navy P-3 “Orion” aircraft continued.

On Thursday, June 12, the 110-foot, U.S. registered God’s Mercy arrived at Key West with 422 refugees on board. This former minesweeper had been chartered by a New Orleans church. The ex-minesweeper had been purchased in Boston for cash and then taken to New Orleans, where she was renamed. The vessel was seized and the operators and crew arrested for importation of illegal aliens. They were released on their own recognizance. All Coast Guard Marine Safety Offices in the eastern United States were alerted to watch for and report any out of the ordinary documentation changes.

On Friday, June 13, the helicopter from Active sighted the 66-foot, U.S. registered shrimper Ocean Queen headed south, 20 miles from Mariel. A party from CGC Diligence boarded her. The operator stated that she was enroute to repair the vessel’s radio and that she had become lost. The boarding party found all radio and navigation equipment to be operating. Seventy-five new lifejackets, still in their wrappers, were on board. Ocean Queen had made a previous voyage to Mariel in April and had returned to Key West with refugees. Cutter Diligence seized the vessel and escorted it to Key West. The vessel and operator were released due to insufficient evidence.

By mid-June, the flood of refugees slowed to a trickle. Over 5,000 vessels had been involved in the exodus. Cuba now released a few boats carrying 50 to 100 people. This occurred three or four days in a week.

Safety at sea dominated the government’s responsibilities in the Cuban exodus, and therefore, this had to be a Coast Guard show. SAR was always first and law enforcement second. Thirteen hundred SAR cases were reported. This is an impressive “bean count,” recalling the late April storm when the service was too busy to count the “beans.” This operation will stand out in Coast Guard annals as one of the service’s greatest achievements. Regrettably, 25 lives were lost, however, thousands were saved by the Coast Guard’s direct and indirect actions.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will be able to learn more about the Mariel Boat Lift, including seeing some of the artifacts recovered during the operation, in Deck 2’s Lifesavers Around the Globe Wing!