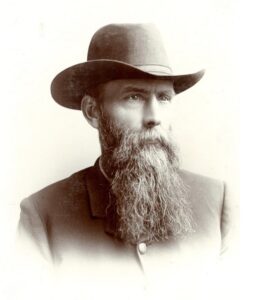

Lawrence Oscar Lawson was born near Kalmar, Sweden, in 1842. His father died when Lawson was 14 years old; however, at the age of 18, young Lawson began sailing with his stepfather, who was a ship captain. In the spring of 1861, Lawson sailed for New York City, and for the next three years made his home there. During the Civil War years, he crewed a vessel that carried supplies to Union Army units in the Chesapeake Bay region.

In the spring of 1864, Lawson moved to Buffalo, New York, where he spent the next three years serving on board merchant vessels navigating the Great Lakes. In December, he arrived in Chicago on board the schooner Tanner and, in 1866, he purchased a piece of land in Chicago’s Jackson Park area to use as a base of operations for commercial fishing. When Jackson Park was formally established in 1868, he sold his land to the local government and, the following year, moved to Evanston, where he resumed commercial fishing. Lawson was the first local fisherman to use pound nets, although his nets were all destroyed in a severe storm around 1878.

In 1878, Lawson became a permanent resident of Evanston. Two years later, in July 1880, he was appointed keeper of the U.S. Life-Saving Service station on the campus of Northwestern Academy (later Northwestern University). His appointment was based on a combination of his merchant sailing experience, small boat handling, and extensive fishing knowledge of Lake Michigan.

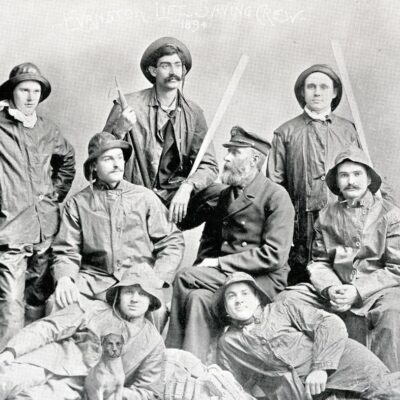

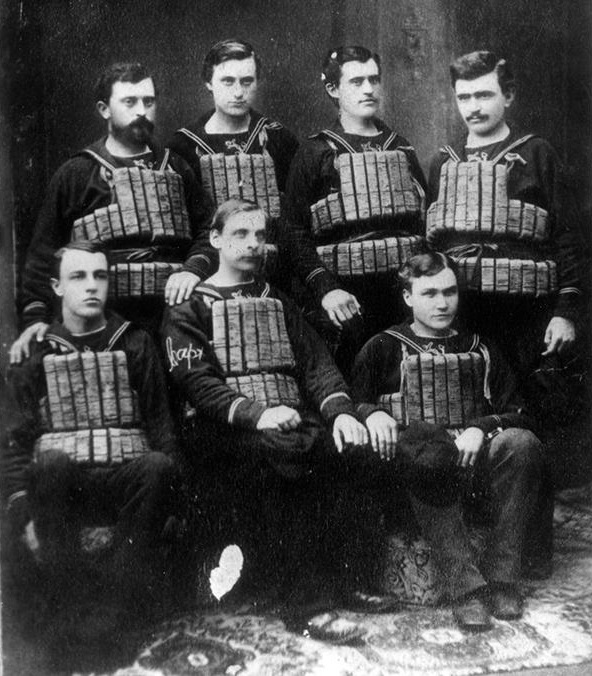

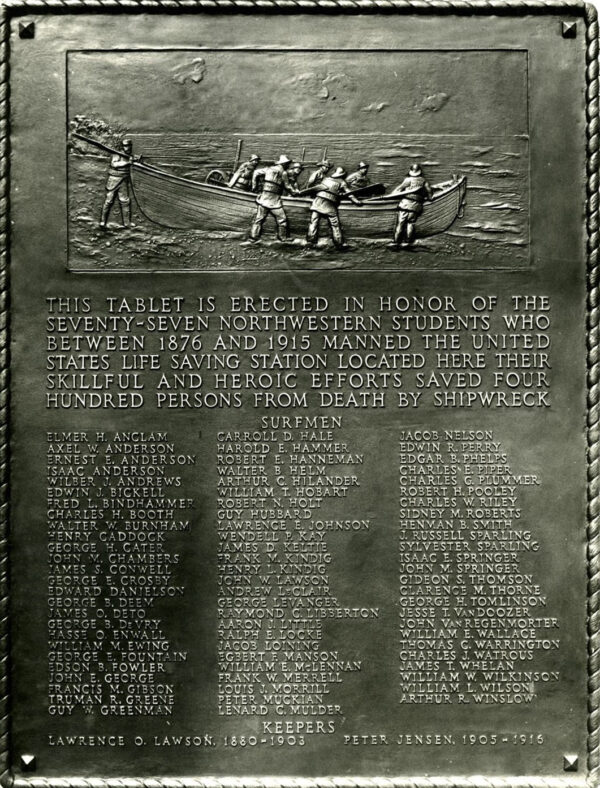

Station Evanston was unique. From 1877 until the 1915 merger of the Life-Saving Service with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service to form the Coast Guard, all of the surfmen at Evanston were volunteers from the student body of Northwestern Academy. Keeper Lawson was very careful to select volunteers best suited to the rigid training and discipline required of a lifesaving crew.

Thanks to their success as rescuers, the Northwestern student surfmen became very popular on campus. Keeper Lawson reported that following either a rescue or a training drill, female students would socialize with student surfmen to the point that it distracted the crew. This was particularly the case during the early years when Northwestern had no student sports teams.

In addition to being an effective and knowledgeable leader, Lawson was also a father figure to the student surfmen who staffed the station. While ensuring that the students were properly trained in using each boat or piece of lifesaving equipment, Lawson promoted their efforts to get a good education, and insisted on the proper discipline for a Life-Saving Service station crew. Lawrence was also a religious man, which likely helped him set a proper example and encourage his students to exert their best efforts. This type of effective leadership wound up paying dividends in a number of successful rescue missions, including the Thanksgiving Day rescue of the S.S. Calumet.

The Calumet Rescue

Keeper Lawson and his student crew’s most famous rescue was the wreck of the steamship Calumet. The following extract from his Gold Lifesaving Medal citation describes the risks taken by Keeper Lawson and his student surfmen:

On November 28 (Thanksgiving Day) 1889, the crew of the Evanston (Illinois) Station, (11th District) Lake Michigan, rendered memorable service in rescuing the crew of the steamer Calumet. Out of Buffalo, New York, she wrecked off Fort Sheridan, Illinois, during one of the region’s fiercest blizzards. The achievement reflected great credit upon the boat’s crew who upheld the reputation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service. The highest praise is also due to the garrison at Fort Sheridan and a party of civilians who aided in getting the surfboat down a steep bluff opposite the vessel. These brave men suffered great hardship in helping to launch the boat after it was lowered from the bluff. It may be justly said that without the aid thus afforded them, the station crew may have been unable to reach the wreck. The result was the rescue of every man from the steamer Calumet.

The ship was bound to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with a cargo of coal. A few days previous, as she was passing through a shallow part of the Detroit River, she ran afoul of an anchor on the bottom and sprung a leak. The damage was so serious that Captain Green, her commander, deemed it prudent to repair as much as practicable and take a steam pump on board to keep the ship afloat. This would have been sufficient to save her had a gale not come on after she passed through the Strait of Mackinac. It was a terrible storm with blinding sleet and snow. The thermometer dropped to 10 degrees. The high sea caused the leak to begin anew. It increased with such rapidity that it got out of control even with the pumps working at full capacity. Another element of danger was that they were unable to find the lights of Milwaukee Harbor.

In this dilemma, the captain resolved to attempt to reach Chicago. Before long, however, the wrecking pump gave out. Green decided to run her ashore to save the lives of his crew. The vessel had not run far before she grounded heavily on a shoal about a thousand yards from shore. She lay off Fort Sheridan, some ten to twelve miles north of the nearest lifesaving station at Evanston, Illinois. This was about 10:30 p.m. on Nov. 27. To save her from pounding herself to pieces, the captain ordered the valves in the ship’s bottom opened to permit her to fill completely. The 18 on board found themselves in a terrible situation. An attempt to save themselves by the boat was out of the question and no help could reach them before dawn.

“There is a large vessel ashore off Fort Sheridan. Come!”

A.W. Fletcher, a resident of Highland Park, was the first to discover her and he quickly sent a dispatch to Keeper Lawson around 12:30 a.m. The message simply said, “There is a large vessel ashore off Fort Sheridan. Come!” Lawson hurried to the railroad station and asked the night operator when the next train would go north. He replied, “Not before 7:30 a.m.” The operator then added that a freight train from Chicago would pass, without stopping, at about 2 a.m. A request was immediately wired to the train dispatcher at Chicago to direct this train to stop at Evanston and take the station crew to Highland Park. As it was too late to couple on suitable cars for the transportation of the apparatus, and as the train would reach Evanston in 35 minutes, there was little time for other arrangements to be made.

Lawson dashed off to the nearest livery stable and engaged teams to haul the boat and beach apparatus to the fort. He then went back to the station and mustered his crew. One man was directed to remain behind, with instructions to wait for the north patrol to come in and then to take the boat and other appliances by the county road. These preliminaries settled, he and the other four men hurried to the railroad station. Joined by the police officer who had delivered the dispatch, the party boarded the train. It was 4 a.m. before they reached Highland Park. They were met by Fletcher, who furnished a guide to conduct them the remaining two miles. The shore at that point was a bold, precipitous bluff some seventy or eighty feet high, with a ravine extending down to the water’s edge. The guide became confused in the darkness and storm and lost his way. This compelled the party to traverse several ravines before they finally reached the place from which they could operate at 5 a.m.

A fire was built by the surfmen to serve as a beacon to the people on the vessel and to warm themselves by while waiting for daylight and the arrival of the lifesaving appliances. The boat and gear arrived at 7a.m. It was then light enough to see that the people on board the ship could not hold out much longer. The keeper decided to attempt to reach her by line rather than risk the lives of the men and the destruction of the boat. Two shots were fired, but each fell a long distance inshore of the vessel. This showed that she was much farther out than had been estimated and, therefore, beyond working range of the lines. Boat service was therefore the only alternative.

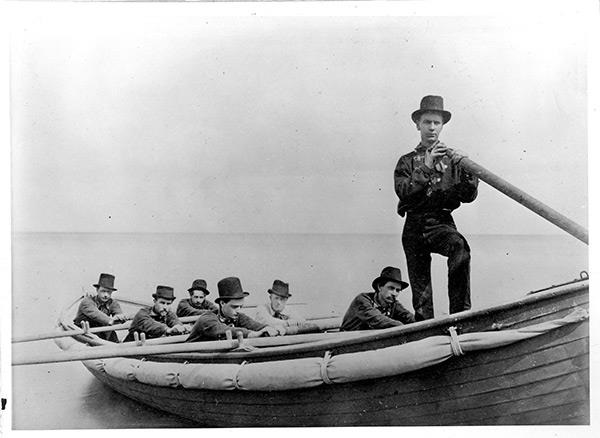

Discarding the gun, the men made immediate preparations for a launch. The place selected for sliding the boat down to the water was the ravine in which the fire had been built. Axes were soon at work cutting a way through the brush wide enough for the boat. Once this was done, the boat was started down the ravine. Soldiers from Fort Sheridan and others eased it to within a few feet of the water. The gully was about three hundred yards to the south of the point directly abreast of the wreck. It was, therefore, necessary to drag it along the narrow shelf of beach at the foot of the bluff.

With the heavy surf rolling in, it was only by watching for their chances between the breakers that any progress could be made. Even then, the gallant fellows were half the time waist-deep and over in the cold icy water, the boat completely filled three times and emptied out the same number. There was also a danger of the men on the inner gunwale being crushed or maimed when the sea struck the craft on its broadside and hurled it against the bank. In spite of this danger and difficulties, the boat was finally gotten to a point a little to the windward of the steamer. As soon as its bow could be pointed lakeward, the crew sprang to their places at the oars. When the next sea lifted the craft, the soldiers pushed it out and the oars were put in motion. The rescuing party was off on their perilous errand.

In crossing the inner bar, they met an immense breaker that nearly threw the boat end over end. The shock of its impact was so great, Keeper Lawson was almost thrown overboard from his post at the steering oar. Before he could recover, a second wave dashed over the boat and filled it to the thwarts. This made the boat almost unmanageable, but with strong and steady pulling of five of the oars, they managed to keep going and soon were beyond the heaviest line of surf.

In the meantime, however, the current had put them far to the leeward. This gave them a long, hard pull directly in the teeth of the gale. The oars were constantly slipping from the rowlocks as both became encased with ice. In the annals of lifesaving effort there can be found few instances so fraught with such hardship and peril, as it was the lot of these brave men to encounter. Yet not a man quailed. It should be noted that the members of this crew were not regular surfmen. Instead, they, with the exception of the keeper, were students of Northwestern Academy (later Northwestern University). Yet nobly, they stuck to their work.

Recovering the ground lost in passing through the breakers was a rough and arduous task. An eyewitness from the bluff declared that at times he thought they would never succeed. The steamer’s crew was clustered about the pilothouse. The vessel was literally encased in ice and the men were stiff after so many hours of exposure. At last, after one of the most perilous trips ever undertaken by a lifesaving crew, they got near enough to the bow of the steamer for Captain Green to throw them a line. Every watcher on the shore, as well as those on board, breathed easier when the boat got alongside. Six of the castaways were, with some difficulty, taken into the boat. After putting a life preserver on each man, a start was made for the shore. Owing to the strong current, the landing was made fully a quarter of a mile south of the point of starting. As soon as the sailors were helped out, they were conducted to the fire on the bluff where the ice was beaten, from their frozen garments and they were supplied with hot coffee.

While this was being done, the boat was emptied and dragged to a point where it could be launched for another trip. Much refreshed by the coffee provided them by the soldiers, the surfmen, after a brief rest, again made their way down to the boat. Another launch was made in the same manner as the first. With the knowledge gained by their previous experience, the boat was from the start headed more to the current and they were not swept so far to the leeward. Consequently, the wreck was more quickly reached, and the trip was made in much less time. Three trips in all were made, six men being landed each trip. Thus, the entire crew of 18 men were saved and without any of them being seriously frostbitten. By the time this work was accomplished, the station men were almost in as bad a plight as the men they had saved.

The assisting party took charge of the boat and, after hauling it back onto the bluff, saw it safely on its carriage in charge of the teamster en route to the station. While this was being done, the surfmen again refreshed themselves with coffee. They then took the first train for Evanston, where they arrived early in the afternoon. A few hours after the rescue of her crew, the steamer broke up completely and, on the following morning, nothing was left of her but the stem and sternpost. It was the opinion of all who were present that, but for the heroic conduct of this student crew, every man belonging to the Calumet must have perished. In recognition of their noble devotion to duty, each man was presented with the Gold Lifesaving Medal, the highest token of its appreciation that the department can bestow. Nov. 28, 1889, Thanksgiving Day, will doubtless ever be remembered by the crew of Calumet, as truly a day for thanksgiving. For on this day the student surfmen of Northwestern and their fearless keeper kept them from a watery grave.

On Oct. 17, 1890, the Congressional Gold Lifesaving Medal was awarded to Keeper Lawson and his six student surfmen. Lawson remained keeper until July 16, 1903, when he voluntarily retired due to failing health. Lawrence Lawson died on Oct. 29, 1912. During his time as keeper, Lawrence and his student surfmen successfully responded to 68 shipwrecks and saved more than 400 lives.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The National Coast Guard Museum will detail the heroic tales of lifesavers such as Lawrence Lawson, and many others, in the Lifesavers Around the Globe Wing on Deck 2 of the Museum.