Having seen Lieutenant Crotty undergo all the trials during my five months in the Manila Bay area, I feel sure that the rigors and trials of a prisoner of war will produce little if any change, and I look forward to the return of Lieutenant Crotty to active duty, for I am sure he will continue to perform his duties in keeping with all the traditions of the Naval and Coast Guard Services.

LIEUTENANT COMMANDER Denys W. Knoll (USN) to Commandant Russell R. Waesche, October 28, 1942

During the defense of the Philippines, in late 1941 and early 1942, Thomas James Eugene “Jimmy” Crotty performed exceptional duty under trying circumstances. He distinguished himself serving as a member of U.S. Navy, Marine Corps and U.S. Army in combat missions against an overwhelming enemy force. During the Japanese invasion of the Philippines, Crotty relied on his diverse skill set and innate leadership skills in the defense of Bataan, and later, at Corregidor.

Born in 1912, Crotty grew up in the old Fifth Ward of Buffalo, New York. During his senior year at South Park High School, Crotty applied for entrance to the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. In the Academy entrance examination essay, he wrote his opinion regarding the nearly ratified London Naval Treaty of 1930. He prophetically noted that the United States “accepted a compromise with England and Japan which gave to these two countries exactly what they wanted . . . while [the] United States gained nothing which was necessary for her to regain her power in the sea.” Later in the essay, he wrote, “War, that deadly horror which spreads destruction and ruin to many innocent and harmless countries, must be abolished.”

At the Academy, Crotty demonstrated his ability as a leader. He played basketball for three years and competed in football all four years, serving as the team captain his senior year. Crotty also served as class vice president and, during his senior year, as class president and company commander. In the 1934 Academy yearbook, the editorial staff wrote, “He will be missed by all of us when we come to the temporary parting of ways, but the future will be enlightened with thoughts that we will serve with him again. Bon Voyage and Good Luck.” For most of Crotty’s classmates, graduation would be the last time they would see their friend.

After graduation, Crotty saw varied assignments across the country. He served on board cutters based out of New York, Seattle, Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and San Diego, including duty on the Tampa during her 1934 rescue of passengers from the burning passenger liner Morro Castle. He also received a Justice Department appointment as special deputy while serving on the Bering Sea Patrol.

In the late 1930s, rising diplomatic tensions between the U.S. and Imperial Japan prompted the American military to send additional personnel and units to Pacific outposts. These military moves set Crotty on a collision course with tragic events unfolding in the Far East. In 1941, the Coast Guard assigned him to the U.S. Navy for specialized training in mine warfare. Crotty probably embraced the opportunity to cross-train with the Navy. As one of his commanding officers wrote, Crotty was “forceful and always enthusiastic about engaging in new problems; sometimes ‘too’ willing to attempt things when perhaps, maturer judgment would suggest further consideration.” In April 1941, Crotty received orders to the Navy’s Mine Warfare School in Yorktown, Virginia. After that training, he joined the inaugural class of the Mine Recovery School located at the Washington D.C. Navy Yard, graduating in August 1941. Crotty had become a leading military expert in mine warfare, demolition and the use of explosives.

After completing mine warfare training, Crotty received orders from the commander of the Navy’s Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Thomas Hart, to sail for the Philippines and join a Navy mine recovery unit at the fleet’s homeport in Manila. On Tuesday, September 2, Crotty concluded a visit to Buffalo and saw his family for the last time. By Friday, he was in San Francisco embarking the passenger liner SS President Taylor on a one-way trip to the South Pacific. The 30-year-old officer thought his deployment would last six months, but he would never see the States again.

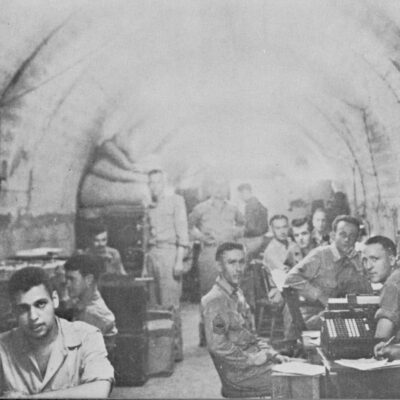

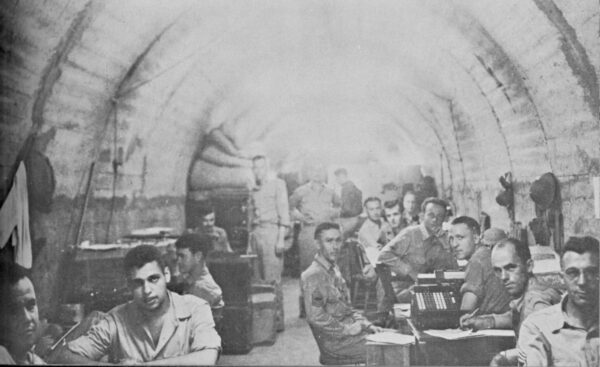

On October 28, 1941, Crotty arrived in Manila and the Navy attached him to InShore Patrol Headquarters at its Cavite Navy Yard. By that time, overall military commander Gen. Douglas Macarthur expected an attack by the Japanese in the first half of 1942. However, on Sunday, December 7, without warning or provocation, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on military installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. And, on Wednesday, December 10, Japanese aircraft bombed and destroyed most of the facilities at Cavite Navy Yard. Advancing enemy ground forces necessitated the movement of American personnel behind fortified lines on the Bataan Peninsula and on the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay. By December 26, the Navy had transferred the 16th Naval District Headquarters from Cavite to Fort Mills, located within rocky Corregidor Island. The next several months would test Crotty’s mental and physical limits.

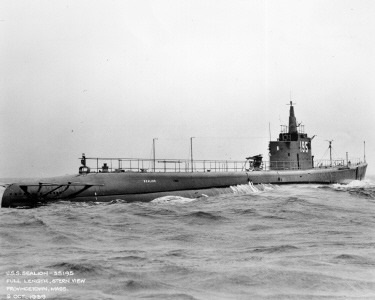

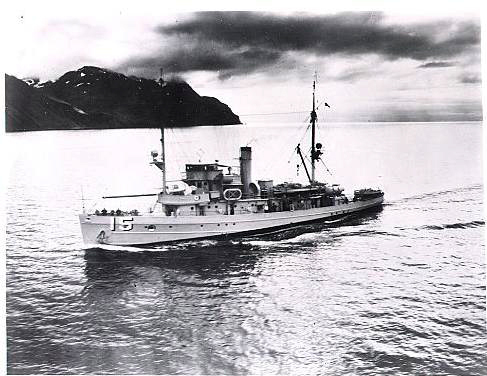

After his Navy command’s transfer to Corregidor, Crotty served a variety of roles with several units. In mid-December, he became second-in-command on board the minesweeper USS Quail, where his shipmates knew him as “T.J.E.” At the same time, Crotty supervised the demolition of strategic civilian and military facilities to keep them from falling into enemy hands. These assets included the fleet submarine USS Sea Lion, which the enemy had damaged during the December 10 air attack. Crotty had the sub stripped of useful parts, filled it with depth charges and blew it up sometime around Christmas Day. Sources indicate that Crotty participated in further demolition work at Cavite and the Navy’s Sangley Point Naval Station, before the enemy occupied the bases around Manila.

While serving on board Quail, Crotty would disappear for days at a time, not only for demolition missions, but wherever he was needed. By January, the Japanese ruled the skies over the Philippines, so grounded naval aviator Cmdr. Francis Bridget assembled approximately 500 unattached Marines, Navy pilots and sailors, and converted them into an infantry unit unofficially named the “Naval Battalion.” In early January, the Japanese had landed troops on the undefended beaches of Longoskawayan Point behind Bataan’s American lines. The Japanese hoped to cut supply lines and flank American and Filipino forces. Bataan’s Army command assigned Bridget and the Naval Battalion the mission of surrounding the Japanese infiltrators and pushing them back into the sea. Crotty rotated over to Bataan during this time to serve in the jungles with Bridget. Late in the month, the two men boarded the Quail, and on the morning of January 27, they coordinated a land and sea bombardment that wiped out much of the Japanese force hidden in the jungle and in coastal caves. Next day, Filipino infantry took over from the Naval Battalion and finished the job a few days later.

During the rest of Crotty’s time on board Quail, the minesweeper provided vital anti-aircraft cover, likely shooting down several low-flying Japanese aircraft. Quail also maintained and patrolled the Navy’s enormous minefield seeded around Manila Bay. This minefield and one planted by the U.S. Army prolonged the survival of American forces by denying the Japanese navy access to Manila Bay; allowing passage of American water traffic between Bataan, Corregidor and other island defenses; and safeguarding U.S. submarines surfacing at night to deliver essential supplies and remove critical personnel. On a number of occasions, Crotty assisted in the minesweeping process, which required two motor lifeboats, a chain and rifles. With the chain suspended between them, the two boats proceeded along a parallel course through the minefield. The chain would snag the live mines, and the boat crews would raise them to the surface and shoot holes in them until they sank. This process helped clear as many as 20 mines with the loss of only a few to detonation.

April proved a pivotal month for Crotty. On Wednesday, April 1, he sent by submarine the last message his family would ever receive. A little over a week later, on Thursday, April 9, the diseased, starving and exhausted American and Filipino troops besieged on adjacent Bataan Peninsula could hold-out no longer and surrendered to the enemy. By mid-April, Crotty transferred from Quail to Fort Mills, Corregidor, and for the rest of the month, he served as adjutant to the headquarters staff of the 16th Naval District.

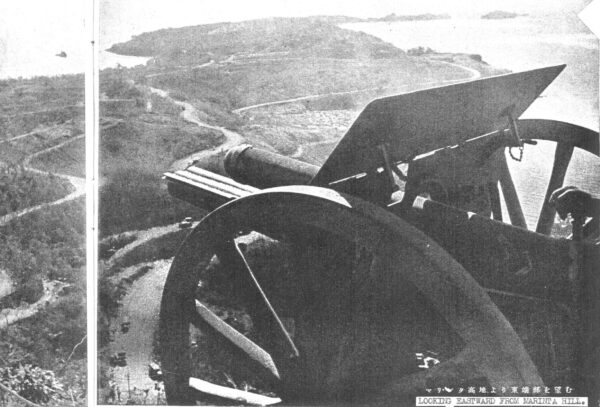

Jimmy also served as a member of the Marine Corp’s 4th Regiment, 1st Battalion, which defended the narrow strip of the island stretching from Malinta Hill to the eastern point of Corregidor Island. Of the four battalions defending Corregidor, only the 1st Battalion would see action against the enemy, which landed on Tuesday, May 5. Eyewitness accounts indicate that Crotty supervised the crew operating a 75mm field howitzer dug-in on top of Malinta Hill, the small rocky mountain that held the island’s underground command center. Crotty’s field piece faced east, toward the oncoming Japanese troops and he served up until American forces surrendered in the afternoon of Wednesday, May 6.

With Corregidor’s capitulation, Crotty became the first Coast Guard prisoner of war since the War of 1812, when the British captured U.S. Revenue Cutter Service vessels and their crews. The Japanese loaded Crotty and his fellow prisoners into watercraft transferring POWs from Corregidor Island to Manila, where they boarded railroad cars bound for a prison camp in northern Luzon. Eyewitnesses indicate that the prisoners stood throughout the lengthy trip and many of the weak and infirm who entered the boxcars never left them alive. Crotty, however, made it to Cabanatuan Prison’s Camp #1, and bunked in barracks reserved for officers with the rank of lieutenant.

Back home in Buffalo, Crotty’s status remained unknown. At South Buffalo’s St. Aquinas Catholic Church, parishioners remembered Crotty in their prayers. Meanwhile, Helen Crotty had received no word of her son’s situation since his April 1 letter. According to Crotty’s older sister, Mary, Helen Crotty watched and waited for the mail carrier every day and seemed to fail visibly each day.

The Crotty family finally contacted Washington D.C., for any information regarding Crotty’s location or condition. However, little was known at Headquarters until late summer, when survivors and escaped prisoners returned from the Philippines. In October 1942, Coast Guard Adm. Russell Waesche, commandant, met with, and later received a letter from, Navy intelligence officer Lt. Cmdr. Denys Knoll. On Tuesday, May 3, Knoll boarded USS Spearfish, the last submarine to depart Corregidor before the island fortress fell to enemy forces. In the letter, Knoll recounted his recollections of Crotty’s character and service in the defense of the Philippines:

“Lieutenant Crotty impressed us all with his fine qualities of naval leadership, which were combined with a very pleasant personality and a willingness to assist everyone to the limit of his ability. He continued to remain very cheerful and retained a high morale until my departure from Fort Mills the evening of May 3rd.”

By the time Knoll penned his lines to the commandant, Crotty had lost the battle against an invisible enemy. In July, a diphtheria epidemic swept through Cabanatuan and, by mid-month, Crotty contracted the illness. Eyewitness accounts indicate that with the camp’s lack of proper medication and health care, he passed away at the age of 30, on Saturday, July 19, only three days after getting sick. A POW burial party interred him in a mass grave outside the prison walls. In a subsequent letter to Crotty’s mother, fellow prisoner and Marine Corps officer, Michiel Dobervich, wrote, “[Crotty’s] friends were heartbroken over the suddenness of his death, but we had to carry on, the same as you do.”

In January 1945, the Army’s 6th Ranger Battalion liberated Cabanatuan Prison, an event glorified in books and movies. However, liberation arrived too late for Crotty whose body was buried in a mass grave alongside thousands of American and Filipino heroes who perished in the insufferable conditions at Cabanatuan. Records indicate that Jimmy Crotty was the only active-duty Coast Guardsman who fought the Japanese at Bataan and Corregidor, operations that merited authorization of the Defense of the Philippines battle streamer for the Coast Guard. He is the only American to single-handedly earn a battle streamer for his service.

The official U.S. Marine Corps history for the defense of Corregidor concludes that those who fought in the ranks of the Fourth Marine Regiment, “whatever their service of origin, were, if only for a brief moment, Corregidor Marines.” As a temporary member of the 4th Marine Regiment, he also qualified for the Presidential Unit Citation, which equates to the Navy Cross Medal on an individual basis.

Like the sacrifices made by thousands of defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, Crotty received little recognition after the war. However, over 50 years after his death, he again was honored for his heroic efforts. In 1999, he was memorialized on the Navy’s EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) Memorial Wall located at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. In 2010, the Coast Guard recognized Jimmy Crotty’s heroism in a ceremony at Buffalo, presenting the Crotty family with the Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart Medal, Prisoner of War Medal, Asian Campaign Ribbon and other fitting medals and awards. In November 2015, the Coast Guard Academy inducted Crotty into its Wall of Gallantry and, in September 2017, Arlington National Cemetery placed a headstone marker in his honor.

In 2019, Crotty’s remains were positively identified and exhumed from the Manila American Cemetery and flown to Buffalo for interment in the family plot. The graveside service received full military honors with Adm. Karl Schultz, commandant, and an EOD flag officer in attendance. In addition, some of his remains were inurned at a ceremony at the Coast Guard Academy columbarium. In a sympathy letter penned to Crotty’s mother over 80 years ago, Crotty’s boyhood friend Bill Joyce wrote, “He left this world a better place than he found it, and I am more than thankful that I was honored to know him.”

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors will have the opportunity to learn more about LT Crotty, and other harrowing accounts of bravery in WW2, in the WW2 Exhibit on Deck 3 of the upcoming National Coast Guard Museum.