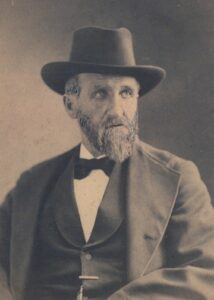

As it has for its other famous heroes, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) has commissioned a new Fast Response Cutter named for Isaac F. “Ike” Mayo, who received the Congressional Gold Life-Saving Medal for heroism during the rescue of survivors from a shipwreck. This essay provides what is known about Isaac Mayo. This includes his life, volunteer service with the Humane Society of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (a.k.a., Massachusetts Humane Society or MHS), his famous rescue, and later generations of his family who served in the U.S. Life-Saving Service (USLSS) as well as the USCG for years after his rescues.

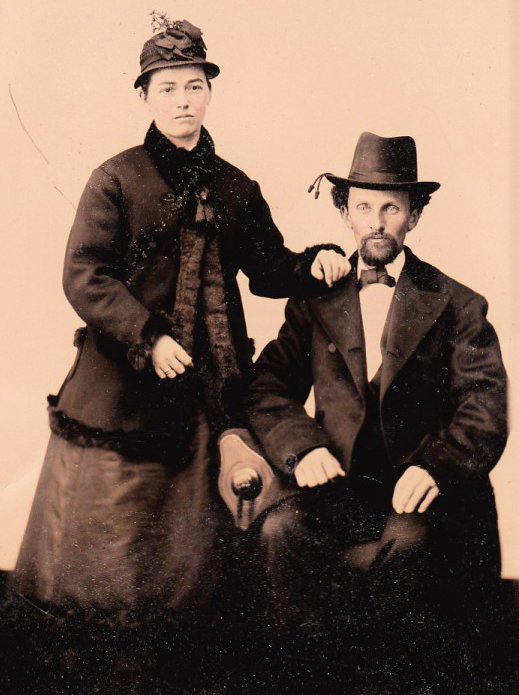

Isaac Franklin Mayo was born on Sept. 2, 1826, in Provincetown, Massachusetts, to parents Joshua and Betsey Mayo. The Mayo family among a number of families first settled in Provincetown, located at the northern end of Cape Cod. On July 23, 1848, at the age of 21, Mayo married Esther T. Small, and, over their 64 years of marriage, they had four children, the oldest unfortunately dying early in adolescence.

Mayo had the reputation of being a very competent and professional mariner, as well as a very kind and compassionate citizen of Provincetown. Provincetown was and still is one of the important seaports that supports the coastal fishing industry in New England. At an early age, Mayo established himself as a professional mariner, fisherman, and local businessman. Over the years that he sailed out of Provincetown, he was the master (captain) of four different sailing vessels, most of which were engaged in the coastal fishing industry or coastal cargo carrying trade. He also owned or was part owner of three vessels.

A Volunteer Surfman in the Massachusetts Humane Society

Like many other local mariners on Cape Cod, Mayo volunteered his professional services as a sailor and boatman to the Massachusetts Humane Society. He quickly proved himself to be a very competent surfman handling boats to rescue shipwreck victims in Cape Cod’s storm surf. One early example was his direct involvement as leader and coxswain of the MHS volunteer crew (consisting of Mayo, then 30 years old; Isaiah Young who later joined the U.S. Life-Saving Service; Amos Chapman; Otis Lovering; and Richard Chapman) that rescued the five surviving crewmembers of the schooner Clarendon on Jan. 5, 1856. The Clarendon had run aground during a storm about 400 yards off the beach along the back shore of Provincetown. Utilizing the local MHS surfboat, it took four attempts to launch through the storm surf, after which they pulled alongside the shipwreck to take off the survivors. For this, all five of the rescuers were awarded the MHS silver medal for bravery.

Rescuing survivors of the Sarah J. Fort

At about 1 a.m., on April 4, 1879, the three-masted schooner Sarah J. Fort with a crew of six men ran aground during a severe winter snowstorm. The schooner lodged on a sandbar about 500 yards off the beach a little over a mile away from U.S. Life-Saving Station Peaked Hill Bars on Cape Cod. Carrying a heavy cargo of coal, the schooner quickly came apart in the storm surf. Although pieces of the ship were noticed along the beach, the shipwreck was not seen by the beach patrol due to the darkness and heavy blowing snow. Finally, around 3 a.m., one of the surfmen patrolling the beach saw the schooner and quickly returned to the station to alert the crew.

Station Peaked Hill Bars had only recently received a new Lyle gun and projectiles. In theory, this gun could have fired a projectile with a messenger line 500 yards out to the shipwreck for the purposes of rigging a breeches buoy apparatus. Keeper David Atkins, however, decided instead to use the station’s older Parrott gun which he thought might reach the ship. While setting up the Parrott gun, the crew of Peaked Hill Bars was joined by crewmembers of the nearby Race Point and Highland lifesaving stations. In the meantime, the Sarah J. Fort began breaking apart, with the hull almost totally underwater. The ship’s three masts broke off one by one leaving only the foremast where the crew had initially taken refuge from the surf. Despite firing a messenger line from the beach to the wreck with the Parrott gun, none succeeded. By noon that day, the foremast broke off, taking two crewmembers overboard to their death and forcing the remaining four crewmembers to seek shelter on the ship’s bow, which was barely above water.

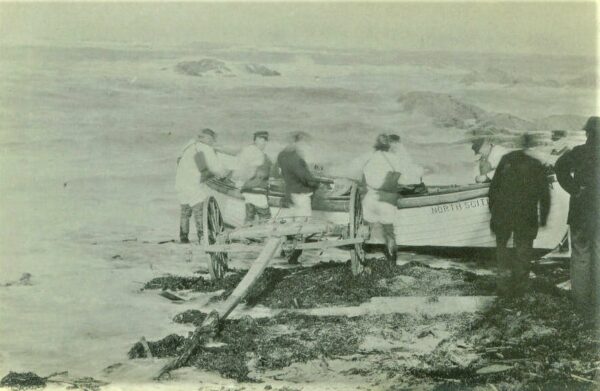

At this point, Keeper Atkins ordered the station crew to bring their 26-foot-long Jersey-type pulling surfboat on its wagon from the station to the beach near the wreck site. Using a mixed crew of surfmen from the different stations, Atkins attempted to launch from the beach to row out to the wreck. On the first attempt, the surfboat was completely swamped and had to return to the beach to be bailed out. On the second attempt, the surfboat was again swamped, but was also thrown by the surf back onto the beach causing such hull damage that the Jersey surfboat was no longer useable.

In the meantime, Provincetown’s citizenry, including Isaac Mayo had gathered on the beach near the wreck site, bringing with them the Massachusetts Humane Society’s lifeboat. This was the same lifeboat used in the 1856 Clarendon rescue and was housed near Provincetown at the Race Point Lighthouse. Unlike the Jersey model, this boat was more like a whaleboat in design, having a more robust but slightly heavier hull structure than the Jersey model. Given that the crews of the U.S. Life-Saving Service stations were now exhausted and suffering from exposure, Mayo took the initiative. He served as coxswain and selected several volunteers (some of whom had served as MHS volunteer surfmen) to man the lifeboat, including Murdoch Kemp, Allen McLeod, Kenneth McPhee, Murdock Chisholm, Benjamin Atkins.

Although the MHS surfboat was also swamped on the first launch attempt and had to return to the beach to be drained, the second launch attempt was successful. Mayo steered the surfboat alongside the shipwreck, which was surrounded on all sides by moving wreckage and floating debris that posed a danger to the surfboat and its crew. Nevertheless, Mayo and his crew were successful in taking the four remaining survivors off the Sarah J. Fort one at a time. Because of the smaller size of the MHS surfboat, the surfmen plus four survivors crammed into the surfboat, impairing the crew’s ability to row in a full stroke of the oars. On their return trip to shore, a rogue wave caused the surfboat to pitchpole end-over-end, throwing everyone into the sea. Fortunately, this occurred close enough to the beach that, with the help of bystanders, everyone made it ashore. Mayo, his crew, and the survivors were rushed to the Peaked Hill Bars station to be warmed up and to change clothing, as they were suffering from hypothermia. In addition, some of the wives of the surfmen (including Mrs. Mayo) had preceded them to the station to prepare hot meals and drinks.

On Nov. 10, 1879, Congress awarded Mayo the Gold Life Saving Medal for his bravery and successful actions leading the crew of volunteer surfmen in the rescue of the four survivors off the wreck of the Sarah J. Fort. The MHS surfboat that was used in the 1856 Clarendon rescue and 1879 Sara J. Fort rescue survived well into the early 1900’s.

Isaac Mayo’s Later Years

Having totally abandoned his maritime pursuits, Isaac took on the role of wheat farmer and acquired land offered to settlers by the federal government. Although farming was a totally new skill set to learn at the age of 50, he prospered in this role and acquired additional land to farm. Isaac lived to the age of 85, passing away on April 6, 1912, in Tower City. He is buried, along with his wife Esther, at Oriska Cemetery in that community.

A Legacy of Service

Although Mayo never served as a surfman in either the U.S. Life-Saving Service or U.S. Coast Guard, members of the extended Mayo family did, primarily serving at the lifesaving stations located on Cape Cod. Based on surfman historical research completed to date, at least eight Mayo family members served in the 1800’s and the 1900’s, well into the modern Coast Guard era up to the beginning of World War II.

Mayo’s legacy also had a major impact on the design evolution of Life-Saving Service rescue surfboats. At the time of the Sarah J. Fort wreck, all of the Cape Cod lifesaving stations had been provided by the USLSS with a Jersey type, square stern/flat bottomed pulling surfboat–a type that had been developed in New Jersey and was thought to be useful for all stations at all locations. This was the type of surfboat initially used by the Station Peaked Hill Bars crew. The extremely unsatisfactory results of this attempted use, followed by the successful use of the more whaleboat-like MHS surfboat convinced USLSS officials that one surfboat design, the Jersey type, was not suitable for all stations. Between 1879 and 1880, this led to the rapid development of the 21-foot-long Cape Cod type and, later, the 23-foot-and 26-foot long Monomoy type pulling surfboats. These were rapidly built and supplied to nearly all the stations in New England to replace the Jersey type surfboats.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The early development and professionalization of lifesaving will be covered in the Early Lifesaving, and U.S. Life Saving Service exhibits on Deck 02. The story of surfmen and the evolution of surfboats of the will be located on Deck 02 as part of the story of the U.S. Life Saving Service.