With a seizure of opium near the entrance to San Francisco Bay in November 1886, cutters of the Revenue Marine Service began a fight against maritime drug smuggling that continues to this day.

The smuggling of opium into the west coast prompted the entry of the Coast Guard—at earlier times called the Revenue Marine and the Revenue Cutter Service—into maritime drug interdiction. The mission would stretch through WWI, wane during Prohibition, and practically disappear during World War II. However, a resurgence would begin in the early 1970s, with the growing popularity of marijuana. A decade later, the Coast Guard’s focus would begin to shift yet again, this time as maritime smugglers began to emphasize moving cocaine over marijuana.

The Beginning: Opium by Sea

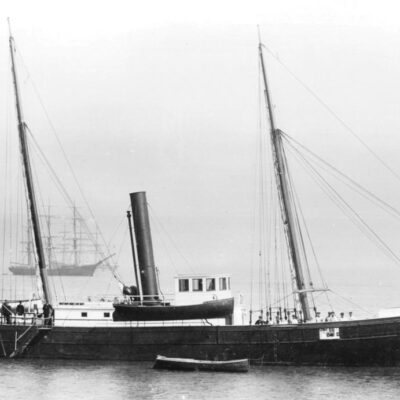

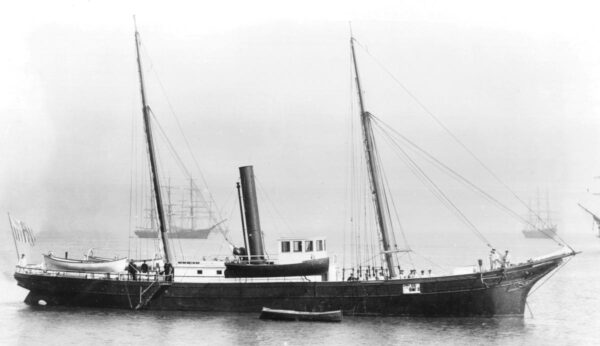

The first at-sea drug seizure was made on Nov. 30, 1886. On the morning of that day, U.S. Revenue Cutter (USRC) Richard Rush, a 175-foot hybrid sail/steamer, had been running a northeast/southwest-oriented barrier patrol off the entrance to the passage through the San Francisco Bar. For two days, the cutter had enjoyed calm seas, clear skies, and balmy temperatures while awaiting the arrival of the SS Rio de Janeiro—which intelligence from the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong indicated would be attempting to smuggle opium into the U.S.

Despite reduced visibility from a light fog that rolled in at around 8:00 a.m., a lookout board the Rush detected the approach of a large steamer at mid-morning. As the steamer neared, CAPT Calvin Hooper directed the launch of a whaleboat and the firing of a blank charge from the Rush’s forward 6-lb rapid fire gun to signal the vessel to slow and prepare to be boarded.

After the Rush’s boat pulled alongside the 345-foot transpacific steamer, a boarding party led by 2nd LT Thomas Benham scrambled up over its side, then proceeded aft as the Rush escorted the steamer into the Bay. At the stern, Lt. Benham found several large packages—each containing a box of 20 tins holding roughly half a pound of prepared (aka “smoking”) opium, for a total of about 350 pounds. He had just made the service’s first known drug seizure at sea.

Opium into San Francisco

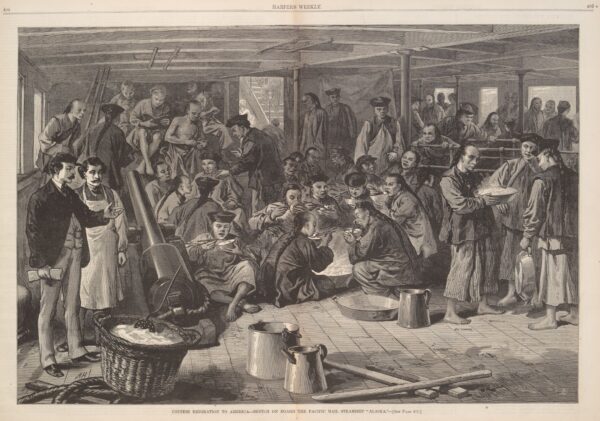

By the time of the Rush’s seizure, opium had been legally imported into the U.S. for decades. Transpacific steamers plying the trade route from San Francisco to Hong Kong via Yokohama returned with Indian and Chinese opium as part of their cargoes. The opium was widely—and legally—used as an active ingredient in medicines and consumer products. However, in the late 1870’s the U.S. experienced a major shift in usage. The highly addictive practice of smoking opium had spread from immigrant Chinese workers to the general U.S. population—with rise in crime and related health issues. Accordingly, the U.S. government implemented a series of actions designed to limit the availability of opium. The most significant action was taken in 1883, when Congress increased the tariff on refined opium from $1/pound to $10/pound.

While a low level of smuggling had been going on since the importation of opium began—mainly by passengers and crew of transpacific steamers smuggling a few to around 50 pounds at time—the low profit margin limited the practice. The new tax expanded the profitability of smuggling opium tenfold and drove an explosion in the practice.

Soon after the levy was implemented, every transpacific steamer arriving in San Francisco from Hong Kong was believed to be concealing several hundred pounds of opium somewhere onboard. These loads were increasingly ferreted out with intelligence that had been gathered by Treasury Agents working out of the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong and telegraphed to the Customs House in San Francisco. Officers and crews of revenue cutters were frequently detailed to assist Customs Inspectors with vessel searches, providing both manpower and technical expertise.

Some smugglers reacted to the success of these searches by seeking to drop off the opium prior to entering San Francisco Harbor. Loads of 300 to 500 pounds would be wrapped in waterproof coverings, attached to a marker float, and dropped from the stern of a steamer for retrieval by a contact boat. Cutters Rush and Chase were kept busy reacting to intelligence of these events, which was shared by the local Collector of Customs.

Only 10 days after having first seized 350 pounds of opium from the Rio de Janeiro, Rush made a second bust. During its first seizure, a boarding party from the Rush had found the drugs on the stern of the steamer—the same light fog that had complicated the Rush’s intercept had likely prevented the smugglers aboard the steamer from sighting their contact boat and dumping the opium over the side for pick up. In the second instance, the poor visibility of the rainy and foggy morning of Dec. 9, 1886, again hindered the smugglers’ plans. Incredibly, this time, in the reduced visibility, smugglers aboard the SS Gaelic mistook the Rush’s whaleboat for their contact and lowered 500 pounds of opium into the very laps of the cuttermen.

A Shift to Washington Territory

Concurrent with the rise in trafficking from Hong Kong to San Franciso, a new, much more efficient smuggling route emerged—aided once again by unintended consequences of new U.S. policy. Besides increasing the tariff to discourage importation, the U.S. had also targeted domestic production of smoking opium. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which severely limited the entry of Chinese Nationals to the U.S., and an earlier ban of the importation of raw opium by Chinese persons and businesses, were designed to eliminate the workforce and material needed to produce smoking opium in the states. While these measures did achieve the intended purpose, operations merely shifted across the border with Canada to British Columbia.

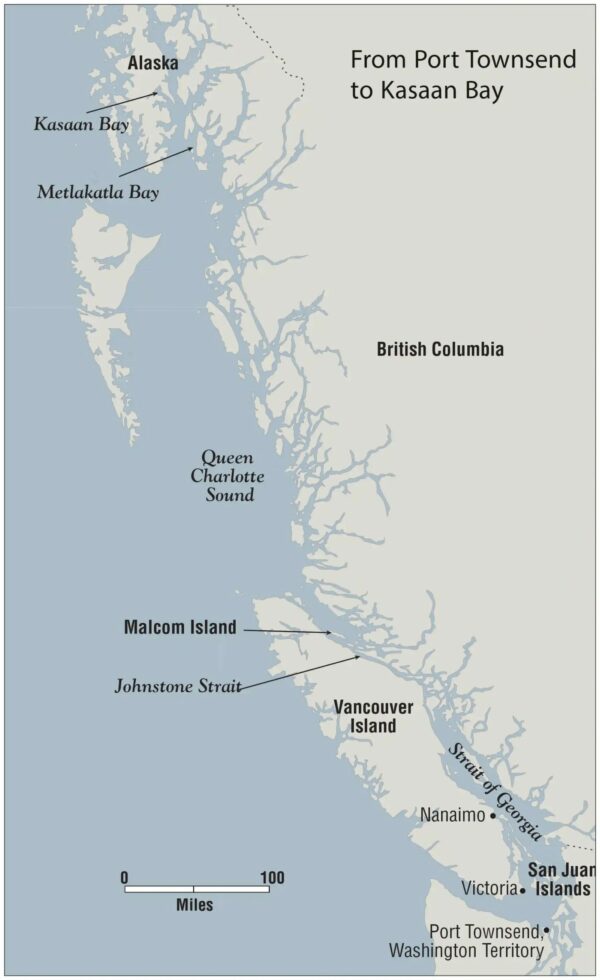

Not only was importation of opium into Canada by Chinese persons still legal, but the import duty remained only $1/pound. Now rather than making a long, trans-Pacific voyage, smugglers could make a short run from Canadian ports such as Victoria, which sat at the southern end of Vancouver Island, less than 40 miles from U.S. territory. Within a few years, every boat of Victoria’s fishing fleet and most coastal freighters plying the region’s waters would be suspected of carrying opium at one time or another.

The Service’s Early Seizures

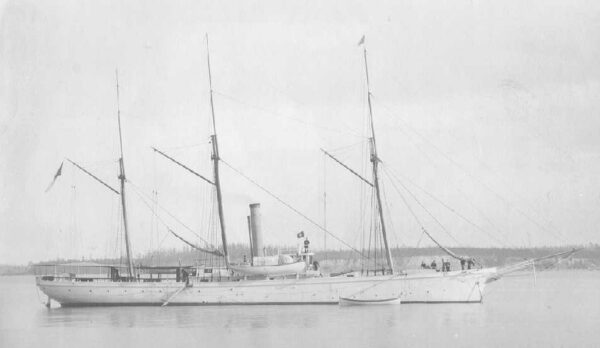

Ten and a half months before the Rush made the first at-sea seizure, the USRC Oliver Wolcott made what appears to be the service’s first solo opium seizure—oddly enough, ashore. On Jan. 14, 1886, a landing party from the cutter more than 3,000 pounds hidden in barrels stored at the Kasaan Bay Salmon Fishery, in southern Alaska. The opium had been concealed there by the SS Idaho—a coastal freighter that ran a route between ports in the Washington Territory, Canada, and southern Alaska. Several weeks earlier, officers and crew of the Wolcott had assisted Customs Officers at Port Townsend, Washington Territory with the seizure of several hundred pounds of opium from the Idaho. The vessel had been released, since no ties between the opium and the owner or officers of the steamer could be proven. However, a disgruntled crewman from the Idaho—upset after having been fired for missing movement after a night of partying on New Year’s Eve—subsequently provided intelligence on the location of additional contraband. Using this intelligence, the Wolcott raced almost 700 miles to Kasaan Bay from Port Townsend to seize the opium before it could be moved by the Idaho.

Three years later the Wolcott would make the service’s first at-sea interdiction that included seizure of both opium and the vessel smuggling it, and the arrest of its crew. Prompted by intelligence from customs agents in Victoria, on Jan. 10, 1889, the Wolcott steamed from Port Townsend to nearby Port Discovery Bay. Once there, the cutter hid behind Clallam Spit, just inside the entrance to the bay. That evening, when the British sloop Emerald entered, one of Wolcott’s boats shot out to intercept it. The Emerald’s master and crew immediately began tossing packages overboard, but the Wolcott’s boarding party quickly scrambled aboard and took control. They found nearly 400 pounds of opium on deck. A subsequent search of the vessel also revealed 12 undocumented Chinese migrants hidden aboard.

The Emerald’s master and crew were arrested, and the vessel and opium were seized. The cutter steamed to Port Townsend the next morning, where the vessel, contraband, prisoners, and Chinese Nationals were transferred to customs officials. The cutter then returned to Discovery Bay and recovered an additional ten pounds of opium that had been jettisoned during the interdiction.

Outdated, Outnumbered, and Outrun

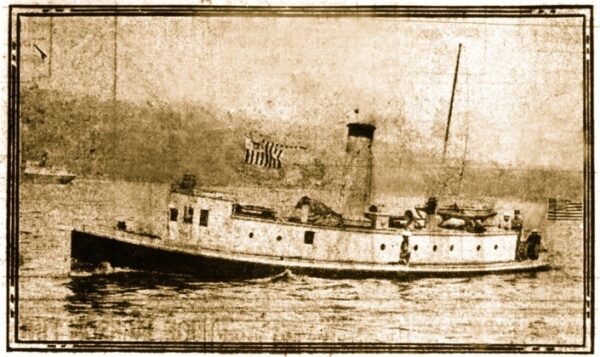

Although the revenue cutters on the west coast did cut into the illegal maritime flow of opium into the Pacific Northwest, they were outnumbered and often outrun by smugglers, especially in Puget Sound and surrounding waters. In response, in 1896 the RMS added two 65-ft steam-powered harbor launches—the Guard and the Scout—capable of making up to 15 knots, to the Port Townsend force. The addition of what would today be called fast coastal interceptors, certainly increased the interdiction capability in the region.

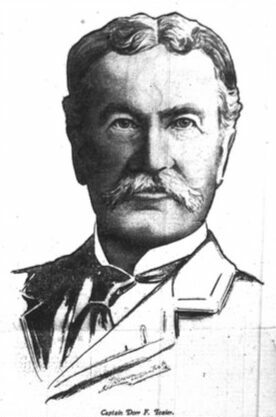

However, Capt. Dorr Tozier, who commanded the small flotilla at the time, found that despite the new interceptors and continued intelligence support from the U.S. Consulate and treasury agents in Victoria, his vessels often still found themselves in hopeless stern chases of smugglers. The speed advantage of his harbor launches was not enough to overcome the inability to coordinate the underway movements of his force—until the advent of radio (then called wireless telegraph).

Recognizing the potential advantages of this new technology, Tozier brokered a deal in 1903 between the newly formed Pacific Wireless Company and the local customs collector. According to the terms of the agreement, Pacific Wireless would install and operate on a test basis, wireless telegraph sets aboard the USRC Grant, (which had replaced the Wolcott), at the Port Townsend Customs House, and at a substation at Friday Harbor, on San Juan Island. This allowed Tozier to alert his launches back in port to intercept incoming smugglers that he had detected while patrolling Puget Sound aboard the Grant. Based on the success of this experiment, Congress later appropriated funds to install wireless aboard the Coast Guard’s 12 cruising cutters.

Displacement of Smuggling Ventures

Adoption of this new technology allowed near real-time coordination of the cutters’ efforts and displaced many smuggling ventures to the land border with Canada. Seizures began to be made as far east as international the rail crossing in northern New York state. When Canada finally outlawed opium in July 1908, even more traffic was displaced from the region. The loss of a secure base for production and the added threat from Canadian law enforcement motivated smugglers to move much of their operations to Mexico.

However, the existence of a large customer base in the Pacific Northwest kept smugglers from totally abandoning the region. Maritime drug smuggling continued throughout World War I, with the Scout making multiple seizures of opium, morphine, and undocumented aliens along the west coast from 1914 to 1917.

By the start of Prohibition in 1920, smugglers had expanded their illegal cargoes to include heroin, morphine, and cocaine, and added new maritime routes from Cuba to the American Gulf and Florida coasts. The smuggling of drugs continued throughout Prohibition—although at a lower volume than alcohol—but little is known of the practice during the World War II era.

Maritime drug smuggling would remain low-key until the early 1970s. By that time, marijuana had become the preferred recreational drug of Americans. Accordingly, it quickly became the preferred cargo of smugglers. Marijuana would dominate the market until the mid-1980s, when the shipment of cocaine began to displace it.

Throughout the entire period, the Coast Guard would continually improve interdiction effectiveness by supplementing its already extensive use of intelligence with the rapid adoption of evolving technology—including radio, air surveillance, and radar.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will get to learn how the Coast Guard’s counter narcotics mission has developed for the past century in the Counter Drug Operations exhibit on Deck 3.