Hispanic American personnel have served in search and rescue operations since the nineteenth century. For example, in 1899, James Lopez of the Provincetown (Massachusetts) Life-Saving Station became the first Hispanic American service member to receive the Silver Lifesaving Medal. But the greatest number of Latino personnel served not in stations along the East Coast, but in Florida and along the Gulf Coast.

In Texas, Coast Guard Station Number 222, also known as the Brazos Life-Saving Station (and currently named the South Padre Island Station), was known for employing several distinguished Hispanic lifesavers. In 1897, surfmen Telesford Pena and Ramon Delgado became two of the first Latinos to join the United States Life-Saving Service. Over the years, Brazos men endured numerous storms and hurricanes, including the deadly Galveston Hurricane of 1900; however, none of these storms proved as memorable as the killer storm of 1919.

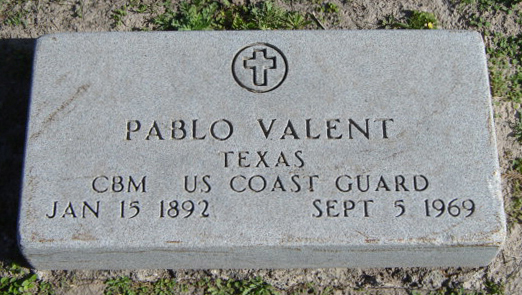

Early September 1919 found Latino lifesavers Pablo Valent, Mariano Holland and Indalecio Lopez serving at the Brazos Station. Valent was born in Corpus Christi, Texas, to Spanish immigrant Antonio Valent and native Texan, Romana Dominguez Valent. In 1912, Valent joined the U.S. Life-Saving Service and would spend most of his career at the Brazos Station. By 1915, he had already advanced to Brazos Station’s Number 1 Surfman (the equivalent to a Boatswains Mate First Class) and recognized by his superiors as “a very efficient man.” Two years older than Valent, Surfman Mariano Holland joined the Life-Saving Service in 1915, the same year it merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to become the modern U.S. Coast Guard. And Surfman Lopez began serving in 1919, only a few months after his discharge from the U.S. Army. He suffered from gas poisoning in World War I, an injury that would plague him until his early death in 1933.

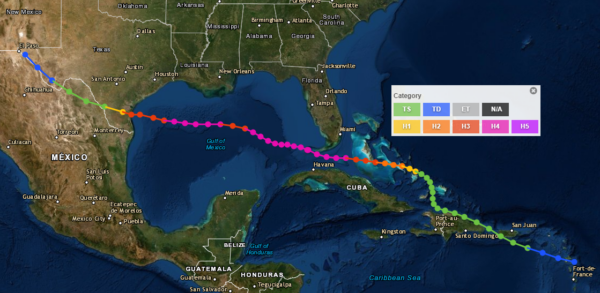

Unknown to these men, a tropical disturbance in the Lesser Antilles had spawned a storm, which began to develop into a Category 4 hurricane. The storm grazed the Florida Keys and slipped into the sheltered waters of the Gulf of Mexico. This hurricane later became known as the notorious “Florida Keys Hurricane,” one of the deadliest storms in U.S. history. Numerous unsuspecting vessels sailed in its path, several of which were lost with all hands.

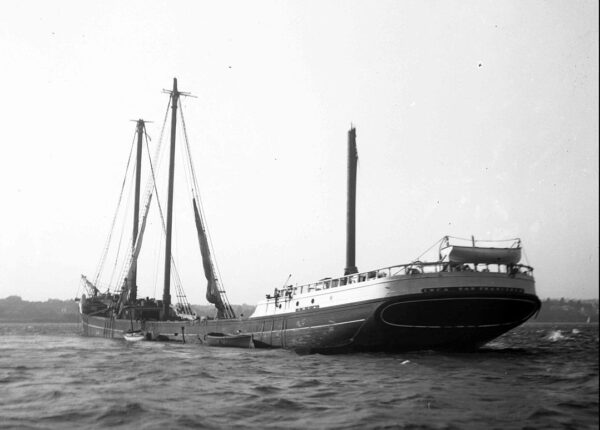

One of the ships in the storm’s path, the 77-ton schooner Cape Horn, had been fishing far out in the Gulf. The storm descended on the schooner and its crew of eight on the night of Saturday, September 13, capsizing the vessel and flooding the hold. The crew managed to cut away the sails and rigging allowing the mastless vessel to right itself. But for the next two days and nights, some of the crew manned the bilge pumps non-stop to keep the hulk afloat while others clung to the foundering vessel as the storm pushed it toward the Texas coast.

At daybreak on Tuesday, September 16, the Brazos Station watch stander spotted the Cape Horn in the distant storm-tossed seas. She was lying low in the water with stumps left for masts and it was obvious that the schooner was about to sink. Station keeper Wallace Reed, Valent, Lopez, Holland, and the rest of the boat crew knew quick action was required. They launched the surfboat in some of the worst sea conditions ever witnessed in the area. Huge waves broke as far as the eye could see and the bar they had to pass to reach the Gulf was a cauldron of cross currents, roiling seas, and angry whitewater.

Nonetheless, the crew deployed its Type “E” 36-foot motor surfboat into the teeth of the storm. The Type E relied on oar power as well as a primitive internal combustion engine. Starting out in the storm-tossed surf, the craft rolled onto its beam-ends throwing the men violently from side to side. The surfboat constantly shipped seas and flew over bruising combers. Several times the surfboat jumped clear of the seas to come crashing down into the trough below. A veteran of 20 years’ service, Reed had never seen such dangerous and confused seas in his life.

After battling the elements for two hours, Valent, Lopez, Holland, and the rest of the men managed to reach the foundering schooner. Cape Horn’s dispirited crew managed to hang-on even with heavy seas surging over the schooner’s deck. To avoid wrecking the surfboat against the submerged vessel, the Brazos crew rowed in the intervals between each breaker to accelerate the surfboat to the side of the hulk. Using this method, they snatched off the survivors one at a time, retreated before the next breaker, then returned to take off another victim.

The lifesavers brought all eight survivors into the boat for the ride back to shore. Unfortunately, the return trip appeared more dangerous than the struggle to reach the ship. The lifeboat was overloaded with 15 men and heavy seas formed huge breakers cascading onto the beach. Turning back was not an option, because the Cape Horn had slipped below the waves shortly after the last survivor left the wreck. As the surfboat neared the shore, Reed found the surf pummeling the beach and had to choose a landing point two miles from his original embarkation point. Though crewmembers Valent, Lopez and Holland were skilled surfmen, the boat shipped seas constantly as huge waves boarded the surfboat from the stern.

With his crew soaked and exhausted and the Cape Horn survivors clutching thwarts and gunnels for safety, the odds weighed heavily against a safe landing. Reed deployed the surfboat’s drogue, a service-issued bucket-like device made of canvas designed to work like a sea anchor. This contrivance controlled the boat’s speed as it surfed over powerful waves and helped Reed keep the boat on course for the beach.

Disaster struck within 100 yards of land when heavy seas burst the drogue. With huge breakers curling all around and the loss of the drogue, the seas could propel the surfboat into the deadly surf, overturning the watercraft and killing or injuring those in the boat. In more than one such rescue attempt, an entire surfboat crew had been drowned. But Valent, Lopez, Holland, Reed, and the rest of the crew managed to hold the boat steady using their oars and, with the aid of the boat’s engine, powered the boat onto the top of a towering wave headed for shore. Riding on the crest of the roller, the surfboat sped toward the beach and, without any added effort by the crew, landed high and dry without spilling out any of the 15 occupants.

The Cape Horn rescue was a complete success. In addition to saving the schooner’s eight men, the Brazos crew skillfully maneuvered their surfboat onto the beach without serious damage to the craft. In its Annual Report for 1920, the Treasury Department noted:

The rescue of the crew of the water-logged schooner Cape Horn on September 16, 1919, by the crew of Coast Guard Station No. 222 (coast of Texas) affords an instance of wreck service in which superb surfmanship, added to dogged grit, overcame well-nigh insuperable difficulties and brought success to hazardous an effort.

For their death-defying feat, the Brazos crew, including Valent, Lopez and Holland received a commendation from Coast Guard commandant William Reynolds, in which he wrote, “The conduct of all who embarked upon this perilous enterprise appears to have been deserving of high praise, and I take great pleasure in commending all concerned for the gallantry displayed.” In addition, the American Cross of Honor Society awarded the men the prestigious Grand Cross Medal for their act of “unusual heroism.” And, in 1921, the men received the Silver Life-Saving Medal from the Coast Guard. This was only the second time in service history that Hispanic American lifesavers had received that medal.

The September 1919 Florida Keys Hurricane was one of the deadliest in Texas history. It came ashore as a Category 3 hurricane and caused immense property damage. In addition, it killed between 600 and 1,000 men, women, and children. It also heavily damaged the Brazos Station and leveled the Coast Guard station at nearby Aransas.

Pablo Valent went on to a successful career in the United States Coast Guard. In 1935, he took command of the Brazos Station (a.k.a. Port Isabel Coast Guard Station), becoming the service’s first Latino Officer-in-Charge. In 1940, Valent retired after 28 years of service in the Coast Guard and passed away in 1969 at the age of 77. In 2018, Sector Corpus Christi honored Chief Boatswain’s Mate Pablo Valent as namesake of its headquarters building, Valent Hall. And, in 2022, the service commissioned his namesake cutter, Fast Response Cutter Pablo Valent.

In the finest traditions of the Coast Guard, Hispanic American hero Pablo Valent and the Brazos Station lifesaving crew demonstrated devotion to duty, going went in harm’s way so that others might live.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The many heroic rescues of the Life Saving Service and early Coast Guard, including the 1900 Galveston hurricane, will be told in the Lifesavers Around the Globe wing on Deck 02 of the National Coast Guard Museum.