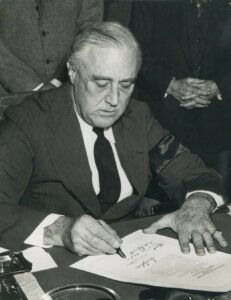

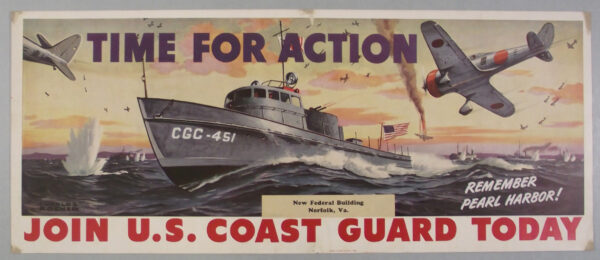

In his war declaration speech, President Franklin Roosevelt labeled Dec. 7, 1941, as a “date that will live in infamy.” On that day, without forewarning or a declaration of war, forces of Imperial Japan attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In the battle, Coast Guard units served alongside the Navy, firing anti-aircraft barrages against the Japanese attackers and performing harbor and anti-submarine patrols.

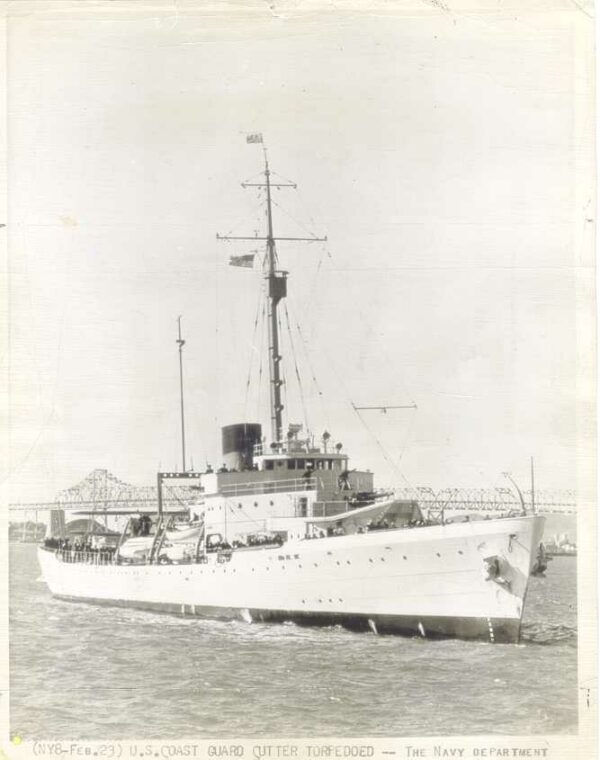

Coast Guard cutters, patrol boats, bases, stations, lighthouse, and personnel assigned to the Fourteenth Naval District supported U.S. naval forces on December 7. These units included high-endurance Cutter Taney and patrol Cutters Tiger and Reliance; buoy tenders Kukui and Walnut; patrol boats CG-400, CG-403, CG-27, and CG-8; a buoy boat and the former Lighthouse Service launch Lehua. Coast Guard radiomen George Larsen and Melvin Bell manned the communications station at the Diamond Head Lighthouse broadcasting that an attack was underway. Coast Guard aviator, Lt. Frank Erickson, who later pioneered helicopter flight, was standing watch at Ford Island before the attack and then took command of an anti-aircraft battery fighting off enemy aircraft.

The Coast Guard was supporting the war effort even before Pearl Harbor. The service was transferred from the Treasury Department to the Navy in November 1941; however, Coast Guard units in Hawaii were serving alongside the Navy since the summer, fully integrating with its Navy counterparts by the time the attack occurred. Earlier, the service participated in the pre-war Neutrality Patrol guarding against attacks by belligerent warships in the Atlantic. And, since June 1941, the Coast Guard had overseen the Greenland theater of operations in air, sea, and ice operations, and there it had seized the U.S. military’s first enemy vessel of World War II.

After December 7, the Coast Guard proved worthy of the service’s motto Semper Paratus-“Always Ready.” The cutter Alexander Hamilton became the nation’s first warship lost in action, suffering the service’s first battle casualties, Jan. 29, 1942. A day later, the Coast Guard-manned transport USS Wakefield delivered allied troops to Singapore, evacuated many of the island’s civilian population and suffered its own casualties from Japanese bombers. In May, the Coast Guard cutter Icarus sank the second U-boat destroyed U.S. forces and captured the first German prisoners of the war.

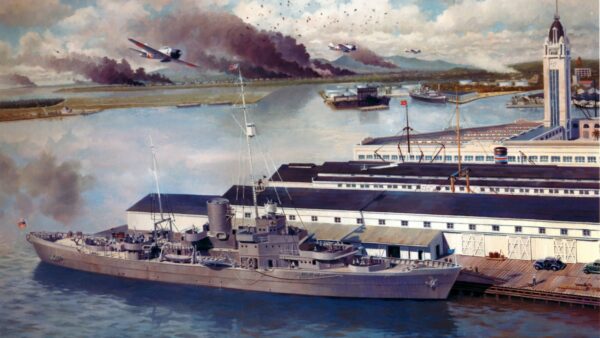

In the first few months of the war, the Japanese military seemed unstoppable in the Pacific. By early summer 1942, the enemy had occupied Guam, Wake Island, Hong Kong, Singapore, vast areas of China, the Philippines, Southeast Asia, and the Dutch East Indies. However, in June 1942, the U.S. Navy vanquished a powerful Japanese fleet in the pivotal naval battle of Midway Island. In August, the U.S. military launched its first land offensive of World War II at Guadalcanal. The struggle for this island proved the first true test of all branches of the American military, including the Coast Guard, against battle-hardened Japanese forces within enemy-held territory. Guadalcanal became a killing field that consumed thousands of men, hundreds of aircraft and dozens of front-line warships. It also became one of the most honored combat operations in Coast Guard history, with service members receiving Purple Heart, Bronze Star, Silver Star and Navy Cross medals, the Presidential Unit Commendation, and the Coast Guard’s only Medal of Honor.

Pearl Harbor had proven a lopsided victory for Imperial Japan. However, by the end of 1942, the tide of the Pacific War had turned in favor of U.S. and Allied forces. For the next two-and-a-half years, the Allies would fight island battles whose names were written in blood against retreating Japanese forces. The Coast Guard participated in all of these major amphibious operations, including Tarawa, Saipan, Guam, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Coast Guardsmen also operated thousands of Coast Guard, Army, and Navy supply ships that supported U.S. troops and Allied fleets in the Pacific.

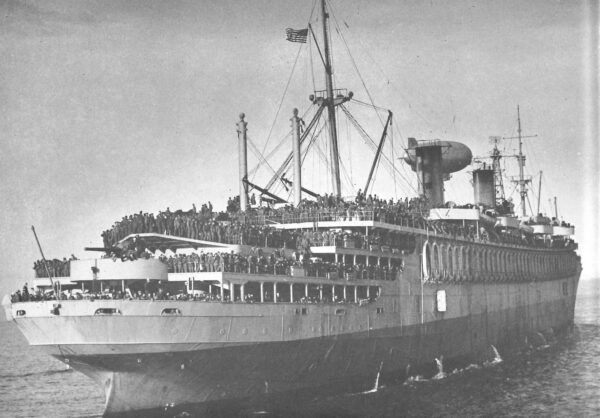

In early August 1945, hostilities came to an end. In the late summer and fall of that year, Coast Guard-manned ships participated in Operation “Magic Carpet,” transporting thousands of troops home to the U.S. And, on Jan. 1, 1946, after providing nearly 250,000 men and women to support the war effort, the Coast Guard left Navy control and returned to its former position within the Treasury Department. Before, during, and after Pearl Harbor, the United States Coast Guard had truly proven itself Semper Paratus or “Always Ready” to perform any naval or maritime mission required to defeat the enemy in World War II.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The National Coast Guard Museum will tell the story of the Coast Guard in the Pacific, in the WWII-Pacific Theatre exhibit in Deck 3’s Defenders of our Nation Wing.