More than a week after Hurricane Katrina left most of New Orleans underwater, hope was fading. Medical experts said it was unlikely anyone was still alive inside the flooded homes.

Lt. Alfred Jackson motored slowly through a drowned neighborhood. From flat-bottomed boats, he and his 18-member team were using spray paint to identify homes that would need body bags . Suddenly, someone thought they heard something.

“Kill the engines,” Jackson ordered.

In the eerie quiet, they heard a metallic tapping. Closer now, they saw a man in a second-story attic window, striking its metal bars with a quarter. He and his bedridden, 87-year-old mother had been trapped for days in water up to their necks.

Jackson’s team sawed through the attic ceiling. The mother was barely conscious, her skin peeling after prolonged exposure to floodwater. They moved her carefully onto the roof, calling in a medevac. Improbably, the boat crew had just saved two more lives.

While Coast Guard helicopters grabbed headlines with dramatic rooftop rescues, the majority of Katrina’s survivors were saved by small boat crews like Lt. Jackson’s. Slowly, quietly, they navigated the submerged city. But because space in the boats was needed for evacuees, their efforts were rarely captured on camera.

“What the boat forces did after Katrina is an untold story in a lot of ways,” said Rear Adm. Shannon Gilreath, who was a lieutenant commander back then.

The Coast Guard famously saved 33,500 people during and after the storm. What most people don’t realize, though, is that two-thirds of these survivors were rescued by boat, not helicopter.

That’s all the more impressive considering the brutal conditions: temperatures in the high 90s, near-constant humidity, and floodwaters contaminated with oil, sewage and dead bodies. Communications were almost nonexistent. Roads were impassable, neighborhoods unrecognizable. Hidden dangers lurked below the filthy water – downed power lines, submerged vehicles, street signs, fences and mystery objects that could tear a hole right through a rescue boat’s hull.

Security was always a big concern. In addition to the ever-present sound of gunfire, boat crews faced armed threats, witnessed people trying to ambush rescue crews, and even saw impersonators in stolen police cars attempting to seize weapons.

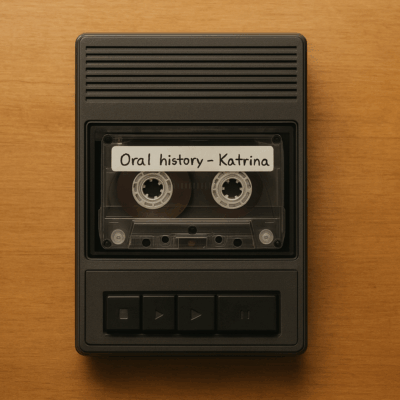

Yet out of chaos, the Coast Guard boat forces managed to build an effective operation on three relentless fronts: Algiers Point, Zephyr Field, and Boat Station New Orleans.

This is their story.

Zephyr Field: From ballpark to lifeline

In the heart of the city, Zephyr Field transformed from a baseball stadium and New Orleans Saints practice facility into a rescue nerve center. Boat trailers, fuel trucks, RVs, and pallets of supplies filled the parking lot. Flat-bottomed punts and john boats were launched by teams like Jackson’s into neighborhoods unreachable by any other craft. Some crews slept on practice fields, wedged between piles of gear.

Once Katrina’s winds died down on Monday afternoon, members sprang into action.

Lt. Cmdr. Daryl Shaffer and Petty Officer 2nd Class Anthony Parrot were part of New Orleans Integrated Support Command (ISC), technically a land unit stationed in Grangeville. But they’d been directed into the city after leadership learned they had boats. State police stopped them when they reached the Causeway bridge early Tuesday morning, warning them the span might collapse. So they unbuckled their seat belts and got ready to jump if needed.

Once across, they navigated debris and destruction to the I-10/610 split where FEMA was staged and planted the first seeds of what would become the Zephyr Field front. They set up an improvised command post and first-aid station.

By 8:25 a.m., their boats were in the water.

“We hadn’t been there long before we heard a whistle,” Parrot recalled. “We looked over and saw a man and a child waving a white towel on a roof. At 9:30, they became the Coast Guard’s first boat rescue.”

On the opposite side of the canal, reservist Anna Steel finally found a place to launch her boat. Steel, who’s currently a commander in the the Coast Guard’s legal advocacy unit, put her law school plans on hold when Katrina hit. She arrived Monday night with several other Disaster Assistance Response Teams (DARTs) from Sector Upper Mississippi River to a city in chaos. “We tried to help then, but were turned away at a lot of places,” she remembers.

Steele spent Tuesday rescuing people in the Ninth Ward. But when they tried to drop off 98 evacuees on one highway ramp, the National Guard wouldn’t let them. “We had to leave, or they were going to pull weapons on us,’ she said.

The DARTs regrouped that night at Zephyr Field, which would become a nerve center of the rescue operation two days later. Gilreath was sent from MSU Baton Rouge to head Coast Guard efforts there with a Unified Command that included FEMA urban search and rescue units, Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries, and a handful of other state and federal agencies.

He quickly consolidated the DARTs with his own fleet, as well as boat crews from District 8 and around New Orleans. Then he began building the infrastructure to support them. “It was primarily a logistical challenge,” he said. “Our people needed places to sleep and shower. They needed security where there was nothing.”

Within days, the Coast Guard had 120 people and 30 boats at Zephyr Field and had rescued more than 4,000 people. The hub would turn out to be the most long-lasting, with the combined efforts for Unified Command resulting in more than 12,000 lives saved.

Algiers Point: How a ferry landing became an escape route

To get thousands of people out of flooded neighborhoods east of the Mississippi river, Chief Warrant Officer David Lewald and his crew from the Coast Guard Cutter Pamlico turned a ferry landing at Algiers Point into an escape route.

Even before the scale of the disaster was clear, Chief Warrant Officer R. David Lewald, commander of the Coast Guard Cutter Pamlico, was leading a flotilla of Coast Guard vessels back downriver to the city.

The Pamlico made it to New Orleans at sunset to find the city dark and burning, with people flashing lights from hotel windows. Their first mission was to ferry personnel from the Naval Support Activity across the Mississippi, but when Lewald arrived, he found scores of civilians there, too. The naval base commander refused to let the Pamlico moor permanently, forcing Lewald to improvise.

So he moored at Algiers Point on the West Bank and began ferrying people there from flooded Chalmette. That first night they moved 15 people at a time in 41-foot boats. By the next day, they had ferries, a tug, and a barge, moving several thousand.

On Sept. 4, with the arrival of the Navy’s amphibious assault ship USS Tortuga, the mission of the Pamlico and the Algiers Point Armada finally ended. Having coordinated and supported the evacuation of more than 7,000 people from a damaged city in which law and order had broken down, the Pamlico could now shift focus to its normal mission: aids to navigation. On Sept. 5th, the tender pushed off the bank and headed downriver bound for Venice at the mouth of the Mississippi. At the time, the crew did not realize that Pamlico’s Katrina response operations would draw global acclaim, but they did know that their work was far from over.

“There’s a reason the Coast Guard was so successful after Katrina,” Lewald says today. “It’s because we pushed decision-making to the lowest level and empowered our people.”

Into the Eye of Chaos

Read more about the Pamlico and the now-famous Algiers Ferry.

-

River Tender Pamlico in Hurricane Katrina

Part I. The ResponseThe Coast Guard’s response to Katrina was not simply wild improvisation. After gaining significant hurricane response experience during Hurricanes Hugo and Bob, planning, training, and extensive preparations were made for a catastrophic weather scenario. Coast Guardsmen in the field would rely heavily on these plans and preparations. These instructions could be summarized as “don’t wait for permission,” and they became the basis for successful improvisation.

-

River Tender Pamlico in Hurricane Katrina

Part II. The CleanupKatrina destroyed between 70-90% of all the navigational aids on the Mississippi River south of Baton Rouge. With rescue and evacuation activities complete, Pamlico’s next priority was to restore aids to navigation and to make the river more accessible for recovery activities.

-

Oral Histories

Interview: CWO3 Robert D. Lewald, USCG

They moved approximately 2,000 people and provided security at the ferry landing. “There were bad people everywhere.” They had encounters with armed people and had to draw their weapons on several occasions. Lewald was threatened personally and had his own bodyguard for a period.

Boat Station New Orleans: Writing their own playbook

On the opposite side of the city, Station New Orleans was waging its own fight. Here, members who had just lost their own homes scrambled to get boats into the submerged streets. Crews motored their boats between floating cars, collapsed houses, and downed power lines. Sometimes the rescues took place off front porches, sometimes in attics where survivors had punched holes through the roof to breathe. The boats would return crammed with people then go back out.

The boat station’s crew evacuated before the storm. BM2 Jessica Guidroz and her crew holed up in a Baton Rouge hotel as Katrina made landfall, then headed towards New Orleans. At daybreak Tuesday morning, they launched their 25 footers in a river that flowed into northwest Lake Pontchartrain and motored back to a place none of them recognized. The cars in the station’s parking lot were now stacked in a pile. There were fish in some of the headlights. Two nearby restaurants had been familiar landmarks – now they were completely gone.

As they pulled up to the station, Stephanie Saladin Wood , then a 23-year-old non-rate, looked up to see a dead horse in a tree. She’d soon learn her house, which was across the street from the station, was flooded up to the roof. “I said, yep, ok,” she remembers. “I already knew that everything was gone and there was nothing I could do. I had to focus on what all these people needed.”

While Guidroz and Wood were away, the Coast Guard’s small boat station was overrun. Looters had stripped the duty rooms. Someone had used a sledgehammer to try to get into the ammo safe. Pregnant women were sleeping on the floor. A man off his meds was screaming.

Guidroz helped the station’s commanding officer, Chief Warrant Officer Dan Brooks, get the situation under control. They spent hours confiscating guns, knives, weed brownies, and booze, and then loaded at least 60 civilians into a cattle truck that would shuttle them to an evacuation point.

“We’re like, ‘Who are all these people?” Guidroz remembered later. “I asked one guy, and he said that they had been airlifted here from off of his roof.”

After restoring some sense of order, the crew got the generator going. That first night they slept in the command center on the floor. A few days later, Station New Orleans was named Forward Operating Base (FOB) NOLA.

First searches, first survivors

At first light, Guidroz took Brooks and her crew out in a boat to survey the area. One of her crewmembers was Dan Grather, a 25-year-old coxswain who had grown up in the area. Later, he would say “it looked like a bomb had gone off.”

“Trees were gone, there were no birds chirping, houses were washed away and there was debris everywhere,” Grather said. “I remember us taking floating gas cans out of the water to see if there was fuel because we knew we’d need some.”

They motored past flooded homes, but didn’t see anyone at first. Then somebody shouted. It turned out to be a couple in their late 30s who’d decided to ride out this hurricane like they’d done before. They’d escaped their flooded house and ridden out the storm in a tree in their front yard. “They were pretty banged up,” said Grather, who still didn’t know where his own family was. “We gave them water and food, treated their cuts and scrapes and brought them back to the station.”

In nearby St. Bernard’s Parish, BM1 Nick Alphonso motored through the neighborhood where he’d grown up. As his team maneuvered around debris, they realized they’d need something smaller for the flooded streets. So they commandeered three recreational boats and brought them back to the station.

“I also needed a better view,” Alphonso remembers. Street maps were next to useless when signs were underwater and houses had floated off their foundations. Plus, floodwater was so high that boats couldn’t pass under bridges, so they needed to find alternate routes in and out of the city. The next morning, he tried calling in a Coast Guard helicopter to scout the area, but when it didn’t show, he marched up to an Army general: “I asked him for just an hour in the air. He said he’d give me 30 minutes.” He took off in a Blackhawk with a young petty officer from another station, Heath Jones – who retired in August 2025 as Master Chief Petty Officer of the Coast Guard. They flew over the wrecked city with a video camcorder, capturing landmarks that would help coxswains navigate.

Living on adrenaline

As members returned, the station got crowded. And evacuees kept arriving. One was a retired cop, so they put him in charge of security. Crews from MSST Galveston, Miami, and Morgan City showed up. A retired auxiliarist named Mike Howell, who had ridden out the storm in a sailboat at the yacht club, offered his vessel for electricity and showers. Toilets were overflowing, and porta potties didn’t come for a week.

For the first four days or so, the two crews Guidroz oversaw, later dubbed “the original eight,” were doing everything from launching boats to doing rescues to running communications. The crews ran low on food and water yet reserved enough to give the people they rescued.

“We ran on stress and adrenaline,” Guidroz said. “We didn’t really sleep that much and we didn’t realize we weren’t sleeping that much because so much was going on.”

Radios barely worked, though occasionally you could get a text message. There were no long-range communications, just satellite phones and a lot of improvisation. The boats went out at first light.

Days fell into a pattern. Get up. Eat. Gather for the morning All Hands to get your assignment – sometimes just maps or atlas pages in plastic bags. Search and rescue till sunset. Come back and get clean, or as clean as you could. Patch holes you got in the boat from going over a fence. Fix the motor. Take turns standing watch. Try to sleep.

The searches were scattered at first, before they developed a system of marking houses that had been searched. They didn’t start using a grid system until Hurricane Harvey.

There wasn’t much you could do about the heat, and boat crews spent hours under the blazing sun. Guidroz remembers they cut their pant legs off. “We did it to get some relief from the heat stress, because someone could get hurt,” she said. The smell of water got worse by the day. “It was like death, oil and petroleum products,” said one crew member.

They launched from any ramp they could find. They drove their boats down submerged streets, hitting curbs, cars, and debris. When they hit a hump in the road, they’d get out and carry the boats by hand.

Confronting desperation

The crew got sent to the University of New Orleans. Some firefighters had called for help trying to evacuate 80 people who had escaped to the higher ground of the campus.

Wood, the non-rate, arrived by boat with Rating Nick Reyes from the station. Disembarking at the shore, they suddenly found themselves surrounded. People were desperate. Some begged for rescue; others just wanted food and water. Some didn’t want to leave.

“There were hundreds,” Wood said. “We told them we had to go back for more boats. One man looked at us and said, ‘I’m going to kill you if you don’t get me out of here.’ I had my hand on my gun the whole time, but we walked backward to the boat. We promised we’d come back, and we did.” Over the next two days they would rescue a couple of thousand people from that area alone.

There were so many people to rescue; it sometimes felt like an assembly line. John Mitchell, a coxswain at the time, says that to this day, he still can’t remember a single survivor’s face. Guidroz remembers one man who kicked his way out of his attic and arrived with a deep leg wound. While they sewed up the wound, she offered him a cigarette to help calm his panic. Weeks later, as she drove past a hospital in uniform, a voice called out: “Hey, you saved my life.” It was that same man.

Others are haunted by the ones they couldn’t help.

Wood remembers the girl who begged her to take a tote bag. Inside was her dead dog. Another woman, who was deaf, sobbed uncontrollably. Her boyfriend told Wood that the flood had pulled her baby from her arms.

“That was the worst,” she said. “She was small, in her twenties. Her boyfriend just stood arms wrapped around her, crying. I said, ‘I’m so sorry’ and then looked away.”

Still, the station’s crew kept going. They did what they could to talk everyone into coming with them. If someone refused evacuation, they were left with a bottle of water, an MRE, or crackers. If there wasn’t enough room in the boat, they’d tell the residents what time they’d return.

Station New Orleans didn’t just survive Katrina. It became the backbone of the Coast Guard’s largest-ever rescue operation. The station evolved into a full-fledged coordination hub. They were asked to tie dead bodies to trees, witnessed coffins floating through town, and searched door-to-door in towns like Hopedale, where no one who stayed survived and the houses all smelled of death.

They also saw the best in each other.

Keeping each other afloat

After two weeks, Grather hit the wall. He still didn’t know where his wife and daughters were. His home was lost. He hadn’t slept. So Guidroz sat up with him. “I was 25 and scared,” he says, “but I wouldn’t have wanted to go through this with any other group of people.”

Guidroz had also lost her home. But she saw it as her role to be strong for the crew. “My job was to keep these guys going,” she said.

“She was phenomenal,” remembers Jason Loerwald, who was a 23-year-old reservist at the time. “We called her Dad. But she was also the boss. She was demanding.”

A mural now lines a hallway of the station. It depicts boats weaving through flooded streets, barges full of evacuees, and names of the people – like Alphonso, Guidroz, Brooks, and Grather – who worked together to save as many as they could. They did their jobs without enough food, enough water, enough sleep, or even the peace of mind that comes with knowing your own loved ones are safe. They did their jobs without news crews documenting their every move. But together, they saved more than 2,500 lives.

Nobody was prepared for a disaster of the magnitude of Katrina, Alphonso said, “But we have at the Coast Guard an innate ability to adapt, and that saved us.”

Or as Grather puts it: “Hurricane Katrina showed a properly trained boat crew can accomplish amazing things if left to their own devices.”

He was eventually reunited with his family, who all survived the storm. Grather retired from active duty in 2021 and now works as a Coast Guard civilian.