2:18 am, April 1, 1946: a terrible roaring sound was heard followed almost immediately by a very heavy blow against the side of the building and about three inches of water appeared in the galley, recreation hall, and passageway. From the time the noise was heard until the sea struck was a matter of seconds.

Chief Hoban Sanford (USCG), Log of Scotch Cap Light Station Tragedy, April 29, 1946

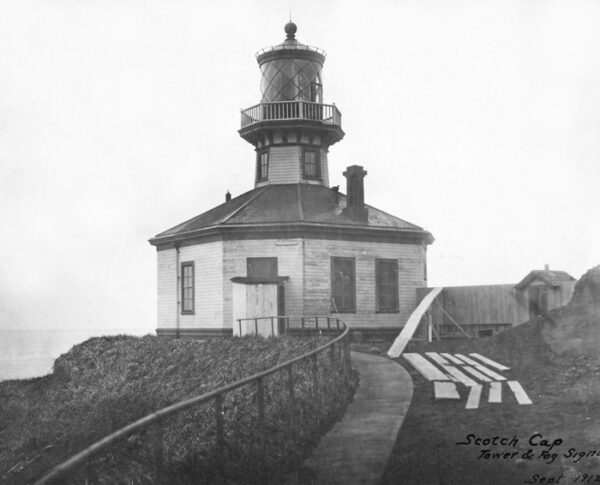

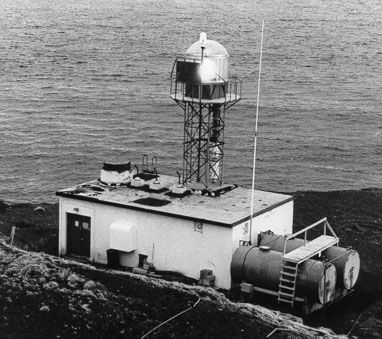

At 1:30 a.m. on April 1, 1946, April Fool’s Day, a massive earthquake struck Alaska’s Unimak Island in the Aleutian Chain, followed by a second quake and a devastating tsunami. The Scotch Cap Lighthouse was destroyed by a wave estimated at well over 120 feet high and its crew of five crushed to death. Structures, including adjacent crew’s quarters, workshop, and receiving antennae were swept away. The tsunami also killed 159 people in Hilo, Hawaii, and crushed structures in South America and Antarctica.

Tsunami Forecast Model Animation: Aleutian Islands 1946 – Courtesy of NOAA

The Scotch Cap Lighthouse was destroyed by a wave estimated at well over 120 feet high. The tsunami also killed 159 people in Hilo, Hawaii, and crushed structures in South America and Antarctica.

In his disaster report, Chief Hobson Sanford stated that the original quake shook his radio direction finding building, located on a bluff above the lighthouse, between 30 and 35 seconds, stating “it creaked and groaned loudly.” An aftershock at 2 a.m., felt worse, but lasted only 15 to 20 seconds. At 2:18 a.m., “a terrible roaring sound” was followed by a heavy blow against the side of the building, which filled with several inches of water. The voltage control regulator on the switchboard in Hoban’s control room was burning and the station plunged into darkness. Sanford broadcast a priority message stating “we had been struck by a tidal wave and might have to abandon the station, and that I believed Scotch Cap Lightstation was lost.” He worried that his transmissions might be taken as an April Fool’s joke.

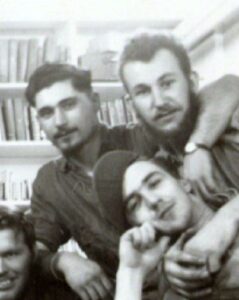

Memories of Scotch Cap veteran Jeano Campanaro

The Scotch Cap radio station had a crew of 25 men, including Radioman Second Class Jean Campanaro, who operated the station’s high-frequency radio direction finder. At age 92, Campanaro vividly remembered the wave shoving a two-and-a-half-ton army truck through the corner of the building where he slept.

Campanaro was born in Salt Lake City in 1926 to Italian-American parents. In 1944, he enlisted at age 18 with two friends who completed basic training with him. They also trained with him at the Coast Guard radio school in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Campanaro next rode the train across the country to Seattle and then took passage on a ship to Ketchikan, Alaska. He boarded a Coast Guard refueling boat bound for Unimak Island getting seasick along the way. When he reached the remote Scotch Cap Station, a dormant volcano not far away was emitting smoke. The rowboat to the radio station and lighthouse proved too small for his collection of books, so they had to be left behind.

An energetic youth, Campanaro spent his free time on Unimak hiking with the station’s three large dogs. On one hike, he was enveloped by a “williwaw,” a sudden storm with blinding snow common to that region. He could no longer see the station and had to climb carefully up a steep cliff in total darkness. Campanaro collapsed and lost consciousness three times, but each time the dogs warmed him with their bodies and revived him by licking his face. More than 70 years later, he credits the dogs with saving his life.

Campanaro vividly remembered the wave shoving a two-and-a-half-ton army truck through the corner of the building where he slept.

Campanaro recalled just after the 1946 tsunami struck, some of the young men panicked and ran out into the night in their underwear. Campanaro and Electrical Technician’s Mate First Class Jack D’Agostino began making emergency repairs. The switchboard was burning, but they grabbed a fire extinguisher and doused the flames. The men worked by kerosene lamps until 5:50 a.m., when an emergency generator was brought online. Throughout the night, they cleaned up the muck and water. In the morning, the crew felt mild aftershocks and an aircraft overflew the station to survey damage, so the crew knew help was on the way. At dawn, Campanaro and his station mates descended the cliff below the radio station and found that the entire lighthouse building had been swept into the sea below. Antennas and telephone poles were smashed against the cliff. Debris was scattered and all of the lower buildings were missing or heavily damaged.

Not long after the quake and deadly tsunami, Campanaro’s father read about the disaster in the Salt Lake City newspaper, contacted Coast Guard Headquarters and learned that his son had survived. In 1946, Campanaro returned home to Salt Lake City, completed a degree in marketing and worked for Salt Lake Hardware. He then served as a social worker retiring in 1980 after a 30-year career. In 1946, he also joined the Naval Reserve and achieved the rank of lieutenant commander in naval intelligence. He married his wife Dorothy in 1951 and they had a daughter. Dorothy passed away in 2017, after more than 65 years of marriage. Campanaro now lives in assisted living, but he still has a sharp mind and vivacious personality.

The Aftermath

After the tsunami struck, Hoban sent out daily search parties. The searchers found random body parts, but the body of Seaman First Class Paul Ness was later found intact. Graves were dug 300 yards from the former lighthouse and remains buried under soil and heavy stones with white wooden crosses and brass plates securely attached. Ness’ father later visited the island and had his son’s body disinterred and moved to Seattle.

Within two weeks of the disaster, the Coast Guard buoy tender Clover arrived and established a temporary unmanned light at Scotch Cap. The radio station crew of 25 remained on Unimak Island until the end of April, with Campanaro baking bread for his stationmates. Next, they were evacuated to Ketchikan, Alaska, and later to California. Today, much of the Asian-Pacific ship trade passes near Unimak Island, where Scotch Cap Lighthouse once stood.

Remembrance

Over 70 years ago, the men of Scotch Cap Light ensured the safety of mariners navigating the treacherous waters of the Aleutian Islands. Long forgotten by the mariners they vowed to protect and serve, they are among the many heroic members of the long blue line who stood the watch never to return.

Please pause to remember the lost souls of Scotch Cap Lighthouse:

- Chief Boatswain Anthony L. Petit

- Motor Machinists Mate Second Class Leonard Pickering

- Fireman First Class Jack Colvin

- Seaman First Class Dewey Dykstra

- Seaman Fist Class Paul J. Ness

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will have the opportunity to learn more about the dangerous work of maintaining remote lighthouses and the courageous men and women who served as their keepers in the Champions of Commerce wing on Deck 4 of the Museum.