Our mechanics were under extreme pressure, they knew many lives depended on their skills. We had mechanics equal to the task, many like Chief Bryzcki, Gus Jablonski and James Boone were among the original group of helicopter mechanics.

Warrant Gunner Robert J. O’Leary, U.S. Coast Guard retired

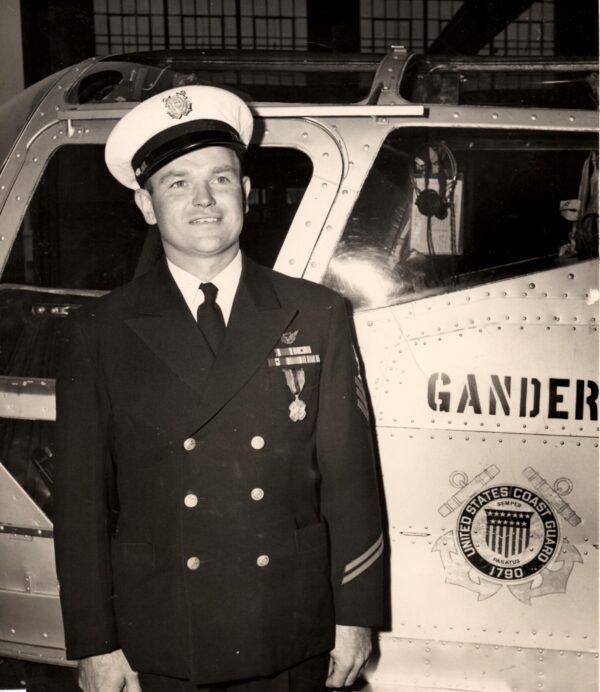

In the early days of helicopter development during and after World War II, the United States Coast Guard played a key role identifying and adapting this new aircraft for lifesaving and other military missions. One of the indispensable enlisted pioneers in this field was Chief Gus Jablonski.

Jablonski was born Sept. 18, 1917, in St. Louis, Missouri, to Kostanty Jablonski and Caroline Marie Hys. In 1938, he graduated from the Franklin Trade School where he excelled in automotive mechanics.

Jablonski enlisted in the Coast Guard right out of school at age 21 and served aboard the Cutter Saranac, a 250-foot Lake-Class cutter homeported in Galveston, Texas. In 1940, he was ordered to Air Station Brooklyn, at Floyd Bennet Field, New York. Until the outbreak of World War II, the unit focused on air-sea rescue with a fleet of Hall-Aluminum PH-2 seaplanes.

With the onset of World War II, Jablonski rose quickly through the ranks advancing to Aviation Machinist Mate First Class (AMM1) on Dec. 1, 1942. However, the crux of this story and what became his lifelong passion began on Oct. 4, 1943, when he was assigned to a five-week “helicopter service and maintenance” training course designed for “Army, Coast Guard and British personnel” at the Sikorsky Factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Jablonski was one of the ‘initial batch’ of students to attend this course.

In an April 30, 1943, Sikorsky letter with a subject line, “MECHANICS’ TRAINING,” author C.L. “Les” Morris (Chief Test Pilot, Sikorsky Aircraft) stated “helicopters are a specialized and completely novel type of aircraft and require maintenance and servicing of a somewhat different nature from conventional aircraft.” The course included two weeks of detailed classroom instruction on all Sikorsky YR-4A helicopter parts supplemented by three weeks (100 hours) of practical shop work on helicopter peculiar items, namely main rotor and tail rotor, transmission, clutch and freewheeling units and control systems. His qualification letter stated Jablonski was “considered qualified to undertake duties of this nature.”

Shortly after Jablonski graduated on November 5, 1943, with his helicopter maintenance qualification, Cmdr. Frank Erickson, the first Coast Guard helicopter pilot and commanding officer, Air Station Brooklyn, included Jablonski’s name in his flight logbook for the first time as a passenger for a 0.1-hour test flight in YR-4B #9 on Nov. 10, 1943.

Two weeks later on Nov. 24, 1943, Jablonski was again listed as a passenger for a 0.3-hour flight with Erickson in YR-4B #9 from the “Sikorsky plant to Daghestan” (a 442-foot British freighter with a helicopter landing pad). Jablonski would serve as the at-sea mechanic for ship-helicopter evaluation trials in Long Island Sound. This was the first of a three-step process to ascertain the feasibility of shipboard helicopter operations for anti-submarine warfare and convoy protection. These trials ran from Nov. 24 to 28, 1943, and involved a U.S. and British helicopter. Both helicopters were assigned to Air Station Brooklyn and crewed by Coast Guard, Navy, and Royal Air Force pilots.

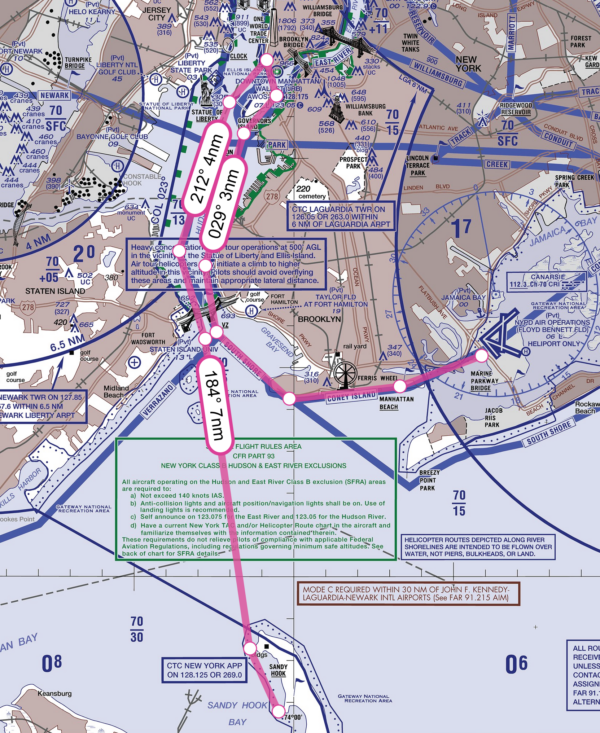

Jablonski did not just maintain helicopters and fly on maintenance test flights. Setting the example for todays “fixers and flyers,” he also flew on operational missions. For example, on Jan. 3, 1944, the destroyer USS Turner, anchored near Ambrose Light, suffered an early morning explosion. A second explosion occurred 47 minutes later, sinking the destroyer. Survivors were brought to a hospital in Sandy Hook, New Jersey. Plasma was badly needed, but a nor’easter raged, and all aircraft were grounded. Normal ground delivery proved impossible.

According to the day’s Flight Operations Report, “Rear Adm. Stanley Parker (Third Naval District and Captain of the Port, New York) called at 1000 January 3 and inquired as to the practicability of sending a helicopter to the Barge Office for the purpose of flying blood plasma to Sandy Hook for the victims of the USS Turner disaster.”

Despite the fact that he had not flown in such conditions, Erickson responded immediately realizing that such a flight could prove that the helicopter was the future of Coast Guard rescue capabilities. Finally, at 10:20 a.m., HNS-1 helicopter #46445, with Erickson at the controls and AMM1 Gus Jablonski in the co-pilot seat, lifted off in swirling snow and gusty winds.

The flight to Battery Park was characterized by extremely low visibility, and strong winds.

“We practically had to ‘feel’ our way around the ships in Gravesend Bay,” Erickson later stated. “Weather conditions were such that this flight could not have been made by any other type of aircraft,” Erickson stated.

Jablonski stayed behind at Battery Park after the plasma was loaded into the helicopter. Blocked by trees to the front, the only way to get airborne again was to back out—a dicey maneuver even for a modern helicopter under ideal conditions. Battered by winds, Erickson deftly coaxed the helicopter into flight. At approximately 10:55 a.m., the HNS-1 finally rose vertically, and landed at Sandy Hook Coast Guard Station at 11:09 a.m. The 40 units of plasma were rushed to the hospital and immediately administered. On Jan. 5, 1944, the New York Times lauded the historic flight:

It was indeed routine for the strange rotary-winded machine which Igor Sikorsky has brought to practical flight, but it shows in striking fashion how the helicopter can make use of tiny landing areas in conditions of visibility which make other types of flying impossible…. Nothing can dim the future of a machine which can take in its stride weather conditions such as those which prevailed in New York on Monday.

Later in 1944, Jablonski was heavily involved in the design, integration, fabrication, and evolution of the first helicopter hoist assembly. On Aug. 11, 1944, Erickson began testing a specially built electric hoist installed on an HNS-1 helicopter. After four days of testing over Jamaica Bay, the electric motor was found suitable for concept demonstration, but it proved too weak and slow for practical application. Erickson and his technical crew switched to a Vickers hydraulic motor that could lift 400 pounds at two and a half feet per second. During new testing, six weeks later, the hydraulic system performed well, and it was adopted for service use.

Jablonski’s efforts were recognized in a letter dated Feb. 15, 1945, from Capt. William Kossler, chief of aeronautical engineering at Coast Guard Headquarters, urging recognition from the Commandant with a subject line of “Official Recognition of Achievement, Personnel of Brooklyn Air Station” that stated,

“The demonstration of the practicality of a power hoist for personnel or equipment, in the R-4 Sikorsky Helicopter has been brought to a successful conclusion at the Brooklyn Air Station.” Jablonski was lauded with the following comments, “the following enlisted men participated in the fabrication and installation of the hoist… [Carl Simon, ACM; Oswald Bachmann, AMM1; James McNeal, AMM1; Gus Jablonski, AMM1 and Water Paton, AMM3] …these men were so interested in the project that they voluntarily worked all night to complete the first hydraulic installation.”

Subsequently, Rear Adm. Lt. Chalker, assistant commandant, issued a Letter of Commendation to Jablonski and the others mentioned above on March 6, 1945.

Labrador

On April 19, 1945, a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Vickers PBV-1A “Canso” (PBY-5A) was transiting from Moncton, New Brunswick, on a ferry flight to Reykjavik, Iceland. It landed on frozen Morbihan Lake, Labrador, due to engine problems. Two of the nine occupants were injured. Very soon after the crash, two C-64 “Norsemen” single-engine bush planes arrived on scene. The first landed and evacuated the two injured personnel, the second crashed and, once again, nine persons needed rescue.

With traditional options exhausted, communications began between U.S. Army Air Force’s Air Transport Command (ATC) and RCAF Eastern Air Command (EAC) in Halifax, Novia Scotia, about using a helicopter for the rescue mission. ATC contacted the U.S. Navy, who advised that there was a Coast Guard Sikorsky R-4B/HNS-1 helicopter available at Air Station Brooklyn, New York.

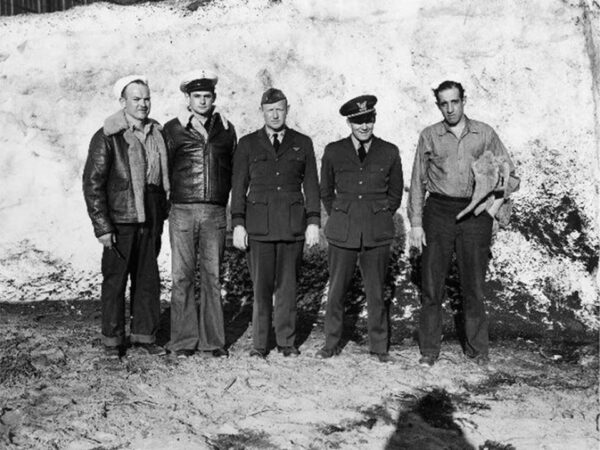

The plan was to disassemble the HNS-1, load it on a USAAF C-54 Skymaster and fly it to Goose Bay where it would be reassembled. It was an ambitious plan, but it had never been done before—the Coast Guardsmen would have to figure out how to do it on the fly. AMM1 Gus Jablonski was chosen as crew chief for the rescue mission, and oversaw the dismantling of the HNS-1, which was then loaded onto the C-54. The C-54 arrived at Goose Bay in the early afternoon on April 29 and work began right away to re-assemble the helicopter. Working through the day and night, the Coast Guard maintenance crew–Chief Forest Giles, AMM1c Irving Zifferblatt and AMM1c Gus Jablonski—had the helicopter assembled and ready for a test flight by the early morning of April 30.

After a test flight in Gander, Lt. August Kleisch flew the helicopter to a base camp that had been set up at Lake Herr about 146 miles south of Goose Bay, which could be supplied by ski planes. After a 180-plus-mile trip, Kleisch landed the HNS-1 at the survivors’ camp around 4 p.m. on April 30th. RCAF navigator Sgt. G.J. Bunnell was the first one taken out by helicopter. Meanwhile, because it was late in the day, Kleisch had to end the rescue operations and overnight at the station. That first night the outside air temperature dropped to 10° Fahrenheit.

The next morning, May 1, Kleisch was up early to prepare the HNS-1 for the day’s rescue flights. Unfortunately, the helicopter’s Warner Super Scarab engine would not start. Kleisch quickly sent a message to Goose Bay to request a portable heater, and crew chief Jablonski. Jablonski and Photographer’s Mate 1st Class Michael Stehney arrived via C-64 with the heater to thaw the engine. Shortly after 12:00 p.m. the helicopter finally started and Kleisch lifted off for the survivor’s camp soon after. The helicopter performed very satisfactorily that day, and Jablonski serviced the HNS-1 at day’s end to prepare for the flights on May 2. Overall, Kleisch had to make nine trips into the crash site over April 30 to May 2, each trip averaging an hour and a half, bringing out one man at a time.

Jablonski was recognized for his performance supporting this rescue by the Commandant, Adm. Joseph F. Farley, in a Letter of Commendation dated March 27, 1946:

You served with distinction in the rescue of nine stranded Royal Canadian Airmen in the Labrador wilds by a Coast Guard Helicopter. Through your assistance the plane was transported and prepared for its rescue flight under difficult and trying circumstances.

Jablonski was instrumental to another early, high profile helicopter rescue effort on September 18, 1946. The Belgian Sabena Airways four engine DC-4 aircraft OO-CBG with 44 persons on board crossed the Atlantic and was scheduled to refuel at Gander Airport in Northeast Newfoundland. However, at some point prior to landing, Air Traffic Control lost contact with the airliner. After determining it had not landed elsewhere, ATC declared an emergency and contacted the Coast Guard Air Detachment Operations Center for assistance.

An inbound TWA flight located the crash site about 20 miles southwest of Gander and remained overhead until Coast Guard PBY-5A #48314 reached the scene and confirmed it was Sabena OO-CBG, and that there were survivors. The area was heavily wooded, and the ground proved to be a very large bog. Aircraft could not land at the crash site, emergency aid supplies were dropped by parachute, as plans were formulated to use Coast Guard helicopters rescue the survivors.

The nearest helicopters were located at the Coast Guard Air Stations Brooklyn, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina. In fact, these were the only helicopters still operating in the Coast Guard after World War II. Similar to the previous rescue near Goose Bay, the fabric covered HNS-1 #39051 and the metal clad HOS-1 #23470 were disassembled for transport. Along with the pilots, maintenance personnel, spare parts, the disassembled helicopters were loaded onto two USAAF C-54 aircraft for the flight to Gander Airport where they were reassembled and tested.

Once again, Jablonski was called upon to lead the disassembly and assembly of the HOS-1 helicopter. He was assisted by: AMM1 James Boone, AMM3 Richard Osborn, AO1 Robert O’ Leary, AMMC Francis Vanneli and AMM1 Ed Gawrysak.

Jablonski was again recognized for his performance supporting this rescue by the commandant, in a Letter of Commendation dated Oct. 10, 1947:

You served for the period 20-22 September, 1946, as a ground crew member of the HOS-1 helicopter engaged in the rescue of eighteen survivors of the Belgian Sabena DC-4 airliner which crashed twenty-four miles southwest of Gander Airport, Newfoundland on 18 September, 1946. With your energetic assistance and technical skill the helicopter was quickly and carefully disassembled for transportation and assembled for the rescue flights, thereby greatly expediting the evacuation of thirteen of the most seriously injured survivors.

In addition, he was recognized by the Belgian government with the Silver Medal of the Order of Leopold II. The order is awarded for bravery in combat or for meritorious service to the benefit of the Belgian nation.

Later, Jablonski was ordered to HOS3/R-5 Training School at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, graduating on April 2, 1948. With this newfound helicopter expertise, the Coast Guard saw fit to transfer him to Coast Guard Air Detachment Argentia, Newfoundland—a fixed wing unit. During his tenure there from July 15, 1948, to May 15, 1949, he once again distinguished himself on an operational mission. On September 20, 1948, his PBY-5A aircrew, including Lt. Charles Lockwood (pilot) and CPO Ben Weaves (copilot), removed eight seriously burned survivors from the Greek freighter SS Orion that caught fire after having grounded in the Strait of Belle Isle, near Newfoundland’s northern tip.

The plane was heavily loaded in taking on all the injured men and required the assistance of Jet Assisted Take-off (JATO) bottles to get airborne—an extraordinary procedure executed in demanding operational conditions. The plane arrived at Argentia at 9:30 p.m. and the injured men in various states of consciousness were conveyed to the Naval Dispensary.

For a third time, Jablonski was recognized by the commandant for his performance supporting a rescue. His Letter of Commendation, dated August 12, 1949, states:

You served on 20 September, 1948, as a crew member of a PBY-5A plane engaged in the removal of eight seriously burned men, survivors of an explosion aboard the Greek freighter SS ORION, from Flowers Cove, Newfoundland, to the Naval Base Dispensary at Argentia, Newfoundland. This timely assistance, rendered under adverse conditions of fog, rain and ice, materially contributed to saving a number of lives.

In May 1949, Jablonski transferred back to Air Station Brooklyn where he would spend the rest of his career. Later, on August 9, he was involved in a high visibility mercy flight to save a polio victim, 21-year-old Sidney Monney, Jr., aboard the Cunard liner Parthia. A PB-1G (a converted B-17 “Flying Fortress” bomber, or B-17J) crewed by Cmdr. A.J. DeJoy (AC); Lt. J.g. W.E. Murphy (CP); RM1 W.P. Stembler (RD); ADC E.P. Farley (OB) and AD1 Gus Jablonski (OB) launched at night and flew from Brooklyn to Halifax, Nova Scotia, transporting a polio medical expert, a heavy iron lung, a portable respirator, an aspirator, and an electric current converter. The doctor and supplies were transferred to Coast Guard cutter Coos Bay, which met Parthia 200 miles offshore. The PB-1G also air dropped additional medical supplies directly to Parthia.

On Dec. 1, 1951, Jablonski was advanced to Chief Petty Officer (ADC). Jablonski retired from the Coast Guard on July 31, 1958, in a ceremony at Air Station Brooklyn. Unfortunately, he passed away from a heart attack just two and a half years later, at age 43, on Jan. 1, 1961—he is buried at Long Island National Cemetery in plot #2M 4051.

Chief Gus Jablonski was a critical figure in the early days of helicopter development. His technical knowledge and hands-on skills helped helicopter visionaries like Capt. William Kossler and Cmdr. Frank Erickson turn Igor Sikorsky’s fragile machine into a tool that could do useful work for the military. While numerous enlisted mechanics participated and contributed to this helicopter maintenance learning curve and legacy, Jablonski stood out as a singular figure that was not only involved, but that drove successful outcomes at numerous critical junctures in the process. As one of the first Coast Guard helicopter mechanics, he helped lay the groundwork for helicopter maintenance procedures and led upgrades of vital systems such as the hydraulic hoist assembly. He led initial, ground-breaking efforts to disassemble and reassemble helicopters for transport to scene, enabling lifesaving missions that demonstrated the unique capabilities of the helicopter to other military services and marketed their extraordinary value to the American public. He then supported these helicopters in austere condition in the Canadian wilderness. He also participated in numerous high-visibility search-and-rescue cases setting the example for today’s fixer-and-flyer mechanics. His efforts were recognized with numerous Letters of Commendation from the commandant and by the Belgian government.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors will have the opportunity to see a detailed history of the use of helicopters in rescue operations through the Aviation and Lifeboat Timeline in the Lifesavers Around the Globe wing of the National Coast Guard Museum.