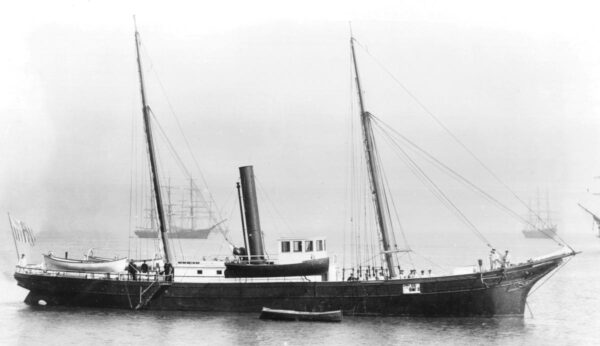

On August 31 the American Steamer George E Starr was seized on Puget Sound by a detail of four officers and 18 men sent from the Wolcott. Two Chinese subjects, together with a quantity of opium, were discovered secreted on board.

Annual Report of the Operations of the Revenue-Marine Service, 1891

In its Annual Report for the Fiscal Year (FY) ending June 30, 1891, the Revenue-Marine Service (RMS)—at times called the Revenue Cutter Service, and a forerunner of today’s Coast Guard—reported the seizure of the steamer George E Starr with undocumented Chinese nationals and opium having been found aboard. For decades, maritime historians have relied on this single “original” source, using some variation of the wording therein, to proclaim the service’s first-ever maritime drug interdiction as having occurred on Aug. 31, 1890. However, while the wording of the passage in the Annual Report is entirely right, the extrapolation by historians since has been almost entirely wrong.

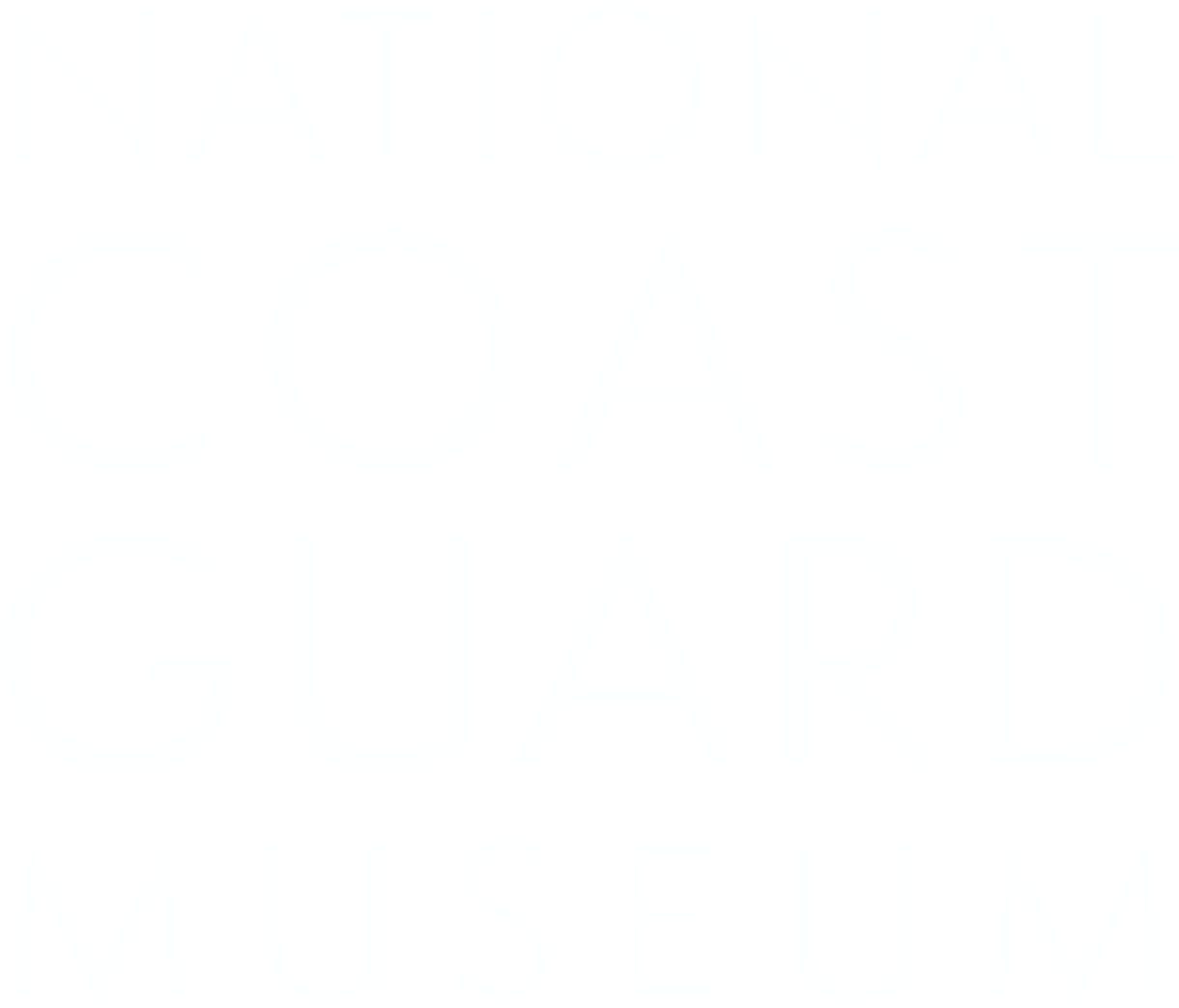

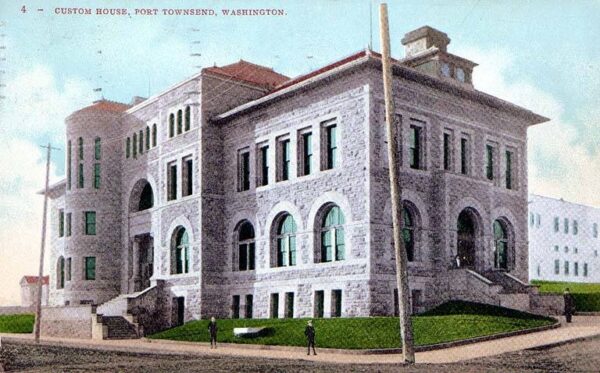

The Revenue Cutter Wolcott made no seizure on Aug. 31, 1890. Indeed, that day was a Sunday, and the cutter was anchored at its homeport of Port Townsend with two duty sections ashore on liberty, and the third engaged in routine vessel maintenance. While the incident appeared in the Annual Report for the FY ending in June 1891—it actually took place two months beyond the scope of that report, on Aug. 30, 1891. The event was likely included to bolster the report’s impact.

On Aug. 30, 1891, the Wolcott was indeed underway in Puget Sound, pursuing intelligence that had been shared with the cutter by Port Townsend’s Collector of Customs, Charles M. Bradshaw. The intelligence specified that the Starr intended to return to the U.S. with a “quantity of undeclared opium” that had been onloaded during its latest trade run to Victoria, British Columbia.

Such opium smuggling ventures from Victoria had become common by 1891. The practice had originally been confined to large trans-pacific steamers returning to San Francisco from Hong Kong, via Yokohama, Japan; however, as opium use in the U.S. exploded in the mid-1880’s, Congress passed several laws designed to reduce the availability of refined or “smoking opium.” The first two of these laws banned import of raw opium by Chinese persons in the U.S. and restricted the entry of Chinese workers to the U.S. This essentially shut down domestic production of smoking opium. The next law increased the duty on the import of smoking opium from ten percent to 100%. Rather than limiting the supply of opium, these laws were instead a smuggler’s gift. Overnight the profit margin for smugglers increased ten-fold.

On the other hand, Canada continued to allow the importation of opium at the former rate of one dollar a pound (which retailed for $10 per pound at the time), and the entry of Chinese nationals, with a $50 entry fee. Thus, the southwest coast of Canada—notably the port of Victoria in New Brunswick, became the locus of both opium production and smuggling, and alien smuggling to the U.S.

At one point, every fishing sloop working out of Victoria and every coastal freighter stopping there was suspected of smuggling opium to the U.S., at one time or another. In response, the U.S. deployed numerous Treasury Agents along Victoria’s waterfront, and the U.S. consulate there ran a string of informants to gather intelligence on prospective smuggling runs. This intelligence would then be sent via telegram to the Customs Office in Port Townsend.

The telegram alerting Collector Bradshaw to the Starr’s intention probably included intelligence that the steamer would attempt to offload the opium before reaching Port Townsend, likely at Port Angeles. Accordingly, Bradshaw arranged for the cutter Wolcott to intercept the smuggler while underway and detailed several Customs Inspectors to assist with the anticipated search.

Getting underway on August 30, the Wolcott headed for Port Angeles, a smaller port than Port Townsend, and not designated as an official entry point for foreign trade. As such, Port Angeles had only two customs personnel assigned—likely the reason smugglers aboard the Starr had decided to sneak contraband ashore there.

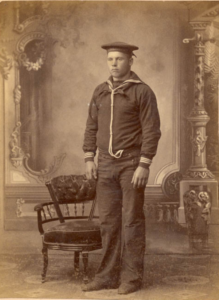

With the customs inspectors aboard, the Wolcott steamed north around the Quimper Peninsula, and then east to Port Angeles, covering the roughly 39 miles in about 4.5 hours. The cutter conducted 17 routine boardings before intercepting the target steamer. An initial at-sea search by 22 cuttermen and customs inspectors turned up two undocumented Chinese persons hidden in a stateroom, and 37 tons of unmanifested Canadian coal in the vessel’s bunkers—but no opium. A vessel could be seized for alien smuggling only if it could be proven that the vessel’s owners or officers were involved; and while purchasing Canadian coal for consumption outside of the U.S. was perfectly legal, and much cheaper than U.S. coal, any amount brought back to the States had to be manifested for assessment of import duties. Accordingly, the captain of the cutter Wolcott, Dorr F. Tozier, seized the Starr before midnight on August 30, for having a “defective manifest.” He left 1st Lt. Albert Buhner aboard to maintain custody as the vessel transited to Port Townsend.

The Starr was escorted to Port Townsend and moored at Union Wharf the next morning. On the afternoon of August 31, Captain Tozier transferred custody of the vessel to the Collector of Customs. While Collector Bradshaw pondered whether evidence was sufficient to forfeit the vessel or merely assess fines for the violations discovered, a subsequent pier-side search led by Customs Inspectors Todd and Brown turned up a total of 30 pounds of opium, worth $400 at the time. The opium had been hidden in the vessel’s galley and in the cook’s bunk.

Even had the Wolcott’s boarding party discovered this opium, the cutter had already made a much earlier drug seizure. More than five years previous, on January 14, 1886, a landing party from the cutter had found more than 3,011 pounds of opium that had been concealed by the steamer Idaho in barrels at a fishery in Kasaan Bay, Alaska. Later that year, on November 30, Revenue Cutter Rush would make the first known “at-sea” drug seizure, finding 350 pounds of opium aboard the transpacific steamer Rio De Janeiro at the entrance to San Francisco Bay.

These seizures marked the beginning of a campaign that would pit a handful of revenue cutters against the widespread maritime smuggling of opium that would continue even beyond the start of Prohibition in 1920.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The story of the Coast Guard’s Narcotics Interdiction mission, from the 1890s to today, will be told in the “Counter Drug Operations” exhibit in the Enforcers on the Sea wing on the Museum’s 3rd deck.