Editor’s note: The following narrative recognizing Lt. Edith F. Munro was delivered by Rear Adm. Blayney on Sept. 27, 1999, as remarks at the dedication of the Douglas Munro Memorial at Cle Elum, Washington.

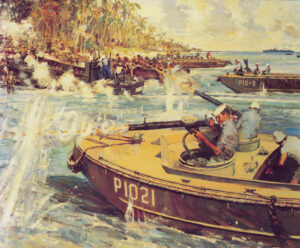

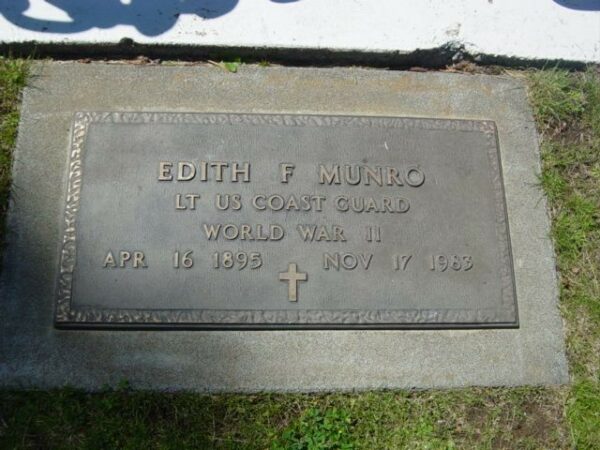

You may have heard the story of Douglas Munro, and his heroism during the invasion of Guadalcanal. His final sacrifice, while saving the lives of 600 Marines, earned him the Medal of Honor, but it has done far more for the Coast Guard as a whole. His name and legend reach far beyond Cle Elum, Washington, where he is buried. His story is taught to Coast Guard recruits within hours of their swearing in. Douglas Munro’s is the only statue in Coast Guard Headquarters. Similar works are also located at the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut, and Training Center Cape May, New Jersey, and on the Seattle waterfront. Douglas Munro stands for all that we are in the Coast Guard. He represents our core values of honor, respect and especially devotion to duty. The Douglas Munro legacy is an enormous part of our spirit and tradition, but there is more to the story. The Munro family carries on its service to the Coast Guard. One person in particular was Douglas Munro’s mother. Edith F. Munro is buried right next to her son.

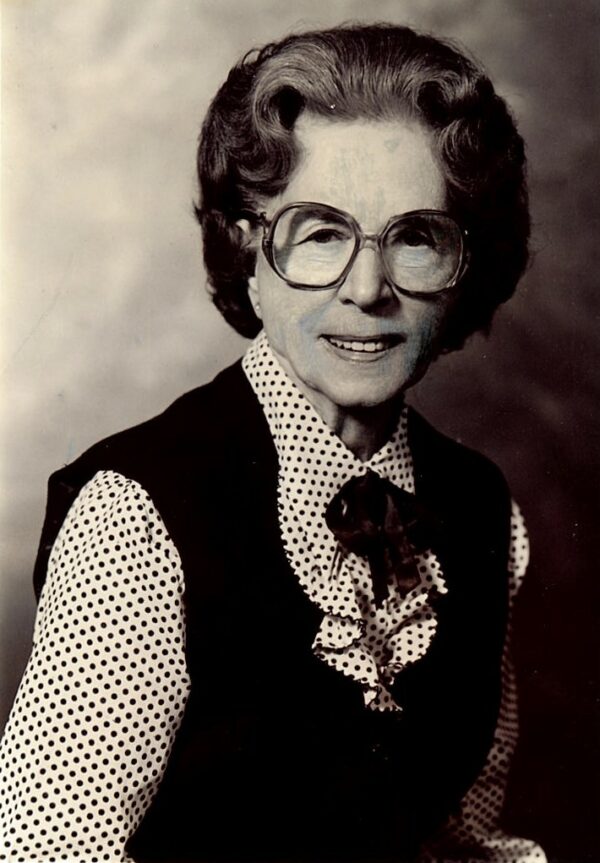

She will always be remembered for raising one of the Coast Guard and Marine Corps’ greatest heroes…but few people know that Munro was also Lt. Munro, of the U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Corps—also known as SPARs.

Shortly after her only son’s death, Munro decided that she would do what she could to carry on his life of service that her son’s death had cut short. Munro took the oath to join the SPARs two hours after accepting the Medal of Honor for her son. When asked why she joined the SPARs she said, “We are a Coast Guard family, through Doug. He loved his service. I am very happy to be eligible to serve in it.” Munro’s statement was released in a May 28, 1943, article in the Palm Beach Post titled, “Medal of Honor Goes to Mother.”

Munro was sent to the U.S. Coast Guard Academy for officer candidate training. She was one of the first SPARs to show up in New London and she was also the oldest. Most new SPAR officers were in their 20s and 30s—Edith Munro was in her mid-40s.

SPAR training was not very well thought out in those days. In fact, it had moved three times before finally being located at the academy—all in the course of a year or so. The curriculum was just as disjointed. While SPARs were intended to backfill administrative positions, so that the men could go to sea, there was no training program for that. Instead, for lack of a better idea, they were instructed in knot tying, military drill, seamanship, and small boat operations. Munro’s daughter, Pat Sheehan recalled her mother’s first letter. It simply stated, “Pat, this would kill you, and it might kill me.”

The SPARs had no uniforms at first, so they were issued large hats to wear with their civilian clothes. They wore the hats everywhere including all small boat operations. Munro, weighed in at barely 90 pounds, but managed to row up and down the Thames River like a seasoned veteran. According to her grandson, retired Coast Guard Commander Doug Sheehan, “The pictures of those women rowing crews in their floppy hats are worth more than a thousand words.”

Because of, or maybe in spite of, that six-week training period at the Coast Guard Academy, Munro was commissioned as a lieutenant junior grade in the Coast Guard SPARs. In actuality, she had been commissioned before the program started, but would not accept any special recognition or favors. She insisted on going through the entire training program like all of the other recruits. By all accounts, she did not need any special considerations—she led the way.

Her first assignment was on the staff of the commandant as a public relations officer. She toured the country telling the Coast Guard story, and that of her son. After about six months, she asked for a transfer. She wanted to do more; she wanted to make a direct contribution.

In 1943, the commandant assigned her to the 13th District, as commanding officer of the Base Seattle Barracks. When the SPARs arrived in Seattle, they were informed that the housing situation was “very bad.” Only a few rooms in the Earl Hotel had been obtained and it was only for a limited amount of time. Many of the women had to stay in the apartments of radiomen and communicators who were on leave or deployed. A few families in the Broadmoor District (a gated residential community) of Seattle had opened their homes to the SPARs. Some stayed in guest rooms while others had to occupy quarters for domestic help or recreation rooms. In June 1943, the Coast Guard took over the Assembly Hotel giving a fully furnished and centralized place for the SPARs to call home.

At the 13th District, Munro really made her mark. Referred to as “The Old Lady,” she was much more than just the CO. She was a teacher, mentor, and mother to a gaggle of wartime recruits. Munro’s new job was not nearly as visible or glamorous as public relations, but it was exactly what she was looking for.

Munro established a name for herself almost immediately. She separated male and female accommodations in the barracks and established new regulations to smooth the transition of women into the Coast Guard ranks. She streamlined administrative processes, adjusted galley menus for better nutrition, and made appropriate uniform changes to better compliment a diverse workforce. She was the first woman to attend 13th District staff meetings as a member of the staff. Old, misplaced feelings of gender superiority flew out the door, as she became a valued and trusted advisor to Rear Adm. Frederick Zeusler.

Because she was such an involved and caring leader, she really got to the pulse of the 13th District workforce—men and women alike. She gave the admiral a new perspective and greatly increased his knowledge, awareness, and appreciation for diversity. Munro was one of the Coast Guard’s first gender policy advisors. She was way ahead of her time, and Adm. Zeusler knew and respected that.

Her first year, Munro was given the honor of being designated SPAR of the year. At the conclusion of World War II, when sailors returned and SPARs moved back home, Munro received a commendation medal. Those familiar with that era know that individual medals for non-combat service were exceedingly rare. Munro had truly done something special.

Munro’s dedication to the Coast Guard and to America continued for the next 50 yearslong after her days with the SPARs. She attended literally thousands of events and ceremonies and was an active Coast Guard supporter to the end. In fact, she was the honored guest at the 50-year commemoration of Guadalcanal—just a year before her death.

Like her son, Edith Munro embodied the Coast Guard’s core values of honor, respect, and devotion to duty, long before those words were put to paper. She did what needed to be done. Munro lived a life of service and sacrifice. Remembering what people like Edith Munro, Douglas Munro, Mike Cooley, and all the others buried here did, is only part of our responsibility. We must also remember how and why these heroes did what they accomplished.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: National Coast Guard Museum visitors will have more opportunity to learn about Edith and Douglas Munro, and the SPARs in the “Defenders” wing on Deck 03.