Following a decades-long pause that began soon after the end of Prohibition, the Coast Guard was once again called upon to combat maritime drug smugglers in the early 1970s.

Shortly after 6 p.m. on May 3, 1971, Coast Guard Cutter Point Barrow, a Coast Guard 82-foot patrol boat, raced outbound past the Golden Gate at the entrance to San Franciso Bay. Point Barrow then headed for a 57-foot converted shrimping vessel loitering a few miles offshore. The former fishing vessel fit the description of a suspected pot smuggling boat, Mercy Wiggins, which had been sighted to the south earlier that day by a U.S. Navy aircraft.

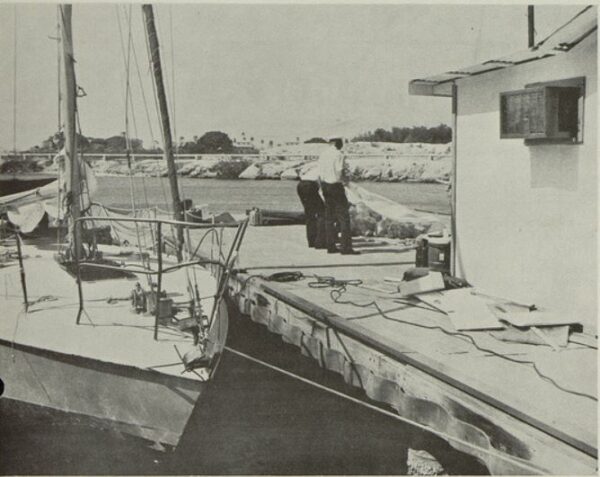

Although the suspect immediately attempted to escape to seaward, Point Barrow overtook them in about 20 minutes. In a position about ten miles southwest of Agate Beach, U.S. Customs Service special agents Erson Kern and William Wagoner boarded the suspect from the cutter, and immediately encountered two men. James Olson, the vessel’s captain, greeted the agents with the now famous line: “Please Gentlemen, you don’t need guns. We are professional smugglers, not gangsters.” Both Olson and his crewman, Gorden A. Maack, were arrested minutes later, after the Customs agents discovered 333 plastic-wrapped bales of marijuana, totaling 10,100 pounds, aboard.

Coincidently, this seizure was made only a few miles from the location where the Cutter Rush, also acting on intelligence from the Customs Service and with several Customs agents aboard, had made the service’s first-ever drug seizure at sea, in November 1886. On that occasion, a boarding party from the Rush had discovered 350 pounds of opium aboard the SS City of Rio De Janeiro.

The Rise of Marijuana Smuggling

By 1971, nearly 40 years had passed since the Coast Guard had last stopped a smuggler at sea. Within a few years of the end of Prohibition, maritime smuggling had declined precipitously…and so had the Coast Guard’s interdiction efforts. No longer were the service’s cutters and planes chasing down liquor-laden vessels in a widely unpopular effort to keep America sober. Instead, over the years the service had come to be seen as the “guys in the white hats.” Fisheries enforcement, protection of marine mammals, marine safety, search and rescue, and national defense became the mission foci of the service.

Then came the 1960s. Although widely known as the decade of civil rights, it was also the decade of counterculture and drug experimentation. During these years, many Americans explored the experience of LSD, heroin, peyote, psilocybin mushrooms, and other hallucinogenic drugs. However, by the end of the decade, the popularity of these drugs had begun to wane. Many new users, wary of the physical and psychological tolls associated with use of hard drugs, turned instead to pot. Marijuana was seen as a gentler, non-addictive alternative. Many Americans, then as today, felt that it should not be lumped together with hard drugs, or even that its use should not be illegal at all.

By 1971, studies estimated that more than half of college students and 40 percent of 18- to 21-year-olds nation-wide in the U.S. had tried smoking pot. Marijuana had become the recreational drug of choice…and nearby Mexico had become the premier supplier to a growing U.S. demand.

Concern over the rising rate of American drug use led Richard Nixon to campaign on the promise of a “War on Drugs.” After his election, he sought to make good on this initiative. His strategy was based on “supply reduction.” Since most of the drugs consumed in the U.S. at that time—and essentially all the marijuana—came across the land border with Mexico, Nixon decided to reduce the supply by attacking the flow there, as drugs were smuggled across the border. The opening campaign of the new “war” was called “Operation Intercept.”

Operation Intercept, launched in September 1969, essentially closed the land border with Mexico for 10 days. Every northbound vehicle was searched, and crossings were brought to a virtual standstill. Although the scale of searches was soon eased to restore commerce, this effort ushered in a new level of heightened border scrutiny that severely restricted drug smuggling by vehicle from Mexico.

As a result, smugglers soon began to shift to maritime routes. Pleasure boats began sneaking marijuana into southern California from northern Mexico. Nine hundred pounds of marijuana were seized aboard a barge at Long Beach, California, in 1970. The owner of the Mercy Wiggins, seized in 1971, later claimed to have made six successful previous runs from Mexico to the U.S.

Despite efforts like these to flank the Mexico/U.S. land border, U.S.-sponsored aerial eradication of growing fields, and an extended drought doomed the efforts of Mexican growers. They were unable to meet the rising U.S. demand, and Colombian and Jamaican growers quickly stepped in to fill the void. Mexican growers would never regain their early market domination. By 1973 the Coast Guard would rapidly reorient its efforts towards interdiction, as it had at the start of Prohibition.

The case involving Coast Guard’s first marijuana seizure at sea began in January of that year. The Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, or BNDD, the forerunner of today’s DEA, had opened a “controlled delivery” case after being approached by the owner of the fishing boat Adventurer III in Miami. The boat, with undercover BNDD agents posing as crewmembers, headed to Jamaica to pick up a load of marijuana. However, when smugglers decided—after the Adventurer III had already picked up the load—to switch to an at-sea transfer to a contact boat rather than returning directly to Miami, the controlled delivery plan was no longer viable. Since the BNDD had no maritime assets and no authority to make arrests outside of the U.S., the agent in charge of the operation turned to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Cutter Dauntless was recalled from a patrol in the Florida Straits, and supported by a BNDD aircraft, was able to intercept the sports fisherman Big L with 1,130 pounds of marijuana that had been transferred from the Adventurer III, near Cat Cay, on the southwestern edge of the Bahamas.

This was the Coast Guard’s first boarding as the lead enforcement entity of a vessel smuggling drugs or alcohol in nearly 40 years. The seizure clearly marked the return of the Coast Guard’s role of stopping smugglers at sea—a major pivot from rescuing vessels in distress, checking safety equipment, and counting fish. The Coast Guard would quickly adapt to and flourish in its new “old” role, seizing more than 1,300 smuggling vessels and removing millions of pounds of marijuana from the maritime pipeline over the next decade.

The Rise of Cocaine Smuggling

Almost 10 years after the start of maritime marijuana smuggling, a gradual shift to hauling cocaine began. The smaller bulk and greater value of cocaine conferred a major advantage over smuggling marijuana: much smaller loads could be moved at a much greater profit. This meant that not only could cocaine be much more easily concealed aboard a smuggling vessel—which decreased the odds of a Coast Guard boarding party discovering it—the reduced-size loads could be moved aboard smaller, faster boats, lowering the chance of being detected in the first place.

The Coast Guard found only a few small cocaine loads—totaling only around 160 pounds—in the early 1980’s. The first interdiction of a boat carrying a major load took place on April 1, 1984. On that day, the USCGC Gallatin, a 370-foot, high endurance cutter, encountered the 33-foot S/V Chinook in the Windward Passage. A boarding party from the Gallatin conducted a consensual boarding of the vessel—one in which the master of the vessel agrees to allow a boarding party to come aboard—to check its registration after initial radio communications raised some discrepancies.

The boarding only raised more suspicion, including the presence of unaccounted for space in the Chinook’s hull. The master, a U.S. citizen, displayed a Canadian flag, but also claimed a homeport of Key West, Florida. The only other person on the boat was also a U.S. citizen. The results of an “EPIC check”—a query of DEA’s El Paso Intelligence Center for intelligence indicating any drug-related activity—revealed that both the master and the vessel had been suspected of drug smuggling since 1975. Based on this intelligence and the discrepancies raised during the boarding, the Coast Guard requested a Statement of No Objection (SNO) from the government of Canada. Although unable to verify the vessel’s registry, Canadian authorities granted permission for the Coast Guard to board and search the vessel, and if illegal drugs were found, to enforce U.S. law. This sealed the Chinook’s fate—if it was Canadian, the Coast Guard was authorized to take law enforcement action; if it were not Canadian, a false claim of flag put the vessel in the stateless category, which would allow any nation’s enforcement units to act. The re-boarding led to the discovery of over 1,900 pounds of cocaine concealed aboard. From then on, cocaine seizures increased yearly, and almost totally supplanted marijuana by 1990—a year in which the Coast Guard seized nearly 17,000 pounds of cocaine.

A Change in Smuggling Vessels and Technology

The shift to cocaine as the cargo of choice for drug smugglers also came with a shift in the type of vessel employed. While some cocaine smugglers continued to use the same types of fishing boats, sail boats, and coastal freighters that had been used to smuggle marijuana, many shifted to smaller, faster vessels—called “go-fasts” or “fast boats.” These were, as the terms suggest, propelled by high-powered outboard engines. Heading north from Colombia via both Caribbean and Eastern Pacific routes, they were hard to detect and harder to run down. Even supported by both long-range surveillance aircraft and cutter-embarked helicopters, cutters were hard-pressed to catch them.

Although the use of fast boats conferred several advantages on smugglers, these advantages were somewhat offset by the Coast Guard’s advances in detection technology and interdiction tactics. In response to increased seizures, smugglers advanced from using simple small fast boats to developing semi-submersibles, and to a much lesser degree, fully submersible vessels. No true, fully submersible vessels have actually been seized in the act of smuggling. Those that the press has called submersibles, have really been semi-submersibles. These are collectively called Low Profile Vessels (LPVs).

A semisubmersible is built such that its deck is awash or nearly awash when loaded. With only a small “conning tower” above the deck—out of which a person can see to steer the vessel—these vessels are difficult to detect both visually and by radar. Despite the small size of LPVs, they are still capable of transporting a multi-ton load over distances of hundreds of miles.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard video by Patrick Kelley

U.S. Coast Guard crews transfer bales of seized cocaine from a semi-submersible suspected smuggling vessel onto Coast Guard interceptor boats and take them aboard the cutter Bertholf in international waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean on Oct. 24, 2019. The semi-submersible was intercepted and cocaine seized the day before by the crew of the Coast Guard Cutter Harriet Lane.

To combat the growing threat posed by growing use of semi-submersible vessels, the U.S. enacted the Drug Trafficking Vessel Interdiction Act of 2008. This law made it a felony for any person to operate an unflagged submersible or semi-submersible vessel, with the intention of avoiding detection on the high seas—regardless of whether or not illegal drugs are onboard. Persons interdicted in a semisubmersible or submersible vessel in international waters may be prosecuted in the U.S.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard video by PO1 Matthew S. Masaschi

Boarding team members from the Coast Guard Cutter Bertholf and Pacific Tactical Law Enforcement Team board a low-profile-go-fast-vessel suspected of smuggling illicit drugs supported by an aircrew from the Coast Guard Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron aboard a MH-65D Dolphin helicopter and an aircrew from the Department of Homeland Security aboard a P-3 aircraft during the cutter’s counter narcotic patrol in the Eastern Pacific Ocean on March 3, 2018. The interdiction was the result of an interagency effort to thwart the flow of illicit narcotics by transnational crime networks.

Technological Innovation

In addition to effective use of intelligence—beginning with the first seizure at sea in 1886—the Coast Guard has been in the forefront of harnessing new technology to counter the shifting tactics of drug smugglers. The first major technological innovation came in 1903.

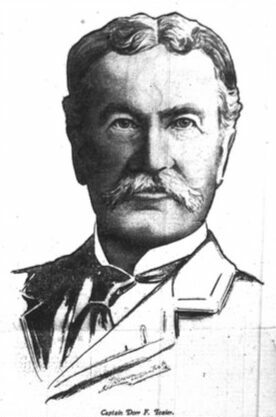

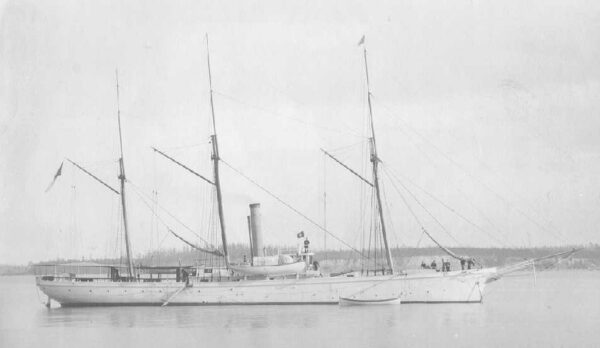

Capt. Dorr Tozier commanded a small flotilla consisting of the USRC Grant, an old and slow sail/steam schooner, and two faster 15-knot steam launches. He was responsible for stopping opium smugglers dashing across Puget sound from Canada to Washington state. However, despite excellent intelligence support from the U.S. consulate and Treasury Department agents in Victoria, Tozier often found himself aboard the Grant in hopeless stern chases of smaller, faster smugglers. Then he brokered a deal between the newly formed Pacific Wireless Company and the local customs collector to install and operate, on a test basis, wireless telegraph (as radio was then called) sets aboard his cutter, and at both the Port Townsend Customs House and Friday Harbor, on San Juan Island, where his launches were stationed. This allowed the Grant to telegraph ahead for an intercept of a faster smuggler by his even faster launches. Based on the success of this experiment, Congress appropriated the $35,000 needed to fund installations aboard 12 cruising cutters, in March 1907.

The next major advance came with the addition of aircraft to the Coast Guard in 1925, during Prohibition. Although limited by the airspeed, range, rudimentary communications gear, and visual-only search capability of early aircraft, this was a major step expansion of the surveillance capability of interdiction forces. The Prohibition era also saw the destruction of contraband and the first instance of airborne use of force, or disabling fire, from an aircraft.

Radar came into common use by surface vessels during and after World War II. By the time the Marijuana War at Sea started in 1973, all cutters were equipped with radar, and most Medium and High Endurance cutters sported flight decks that could accommodate shipboard helicopters. These two advances even further expanded the detection radius of cutters.

HITRON

Another of the Coast Guard’s responses to the threat posed by long range, speedy fast boats, was the formation of the Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron (HITRON). HITRON helicopters were equipped 7.72 mm MGs and a .50 caliber, laser sighted, precision rifle. When a fast boat attempted to outrun a cutter, its assigned HITRON aircraft would quickly overtake the fleeing vessel, and if both commands to stop and warning shots across its bow were ignored, the helicopter’s gunner would disable the go-fasts engines with a shot from the .50 caliber rifle.

Aircraft

The new generation of the Coast Guard’s fixed-wing, long-range surveillance aircraft, such as the HC-130J Super Hercules, is light years ahead of what was in use during Prohibition. Although earlier versions of long-range surveillance aircraft were in use at the start of modern drug interdiction operations, today’s aircraft use a suite of command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) components that are far beyond what was available at that time.

Drones

The Coast Guard also began experimenting with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in 1999. In May 2013, Coast Guard Cutter Bertholf used a version called “ScanEagle” to maintain visual surveillance of a fleeing go-fast boat, which was carrying over 1,000 pounds of cocaine, until it was able to stop the boat. The Coast Guard completed installation of the ScanEagle System aboard all National Security Cutters in 2021 and is planning to expand installation to new Offshore Patrol Cutters as they are delivered. Addition of a UAV to a cutter even further expands the area it can surveille.

The Drug War Today

The Coast Guard integrates its surface vessels and aircraft in a layered approach to stop maritime drug smugglers. Sighting information from maritime patrol aircraft operated by the Coast Guard, Customs and Border Protection, Department of Defense, and allied nations is combined with intelligence from Joint Interagency Task Force South and other agencies, to identify and locate suspect vessels. Additionally, Coast Guard law enforcement detachments embark on U.S. and allied Navy ships to increase its reach worldwide.

This approach enabled the Coast Guard to capture an LPV carrying 12,000 pounds of cocaine on 2019, and to seize more than 150 metric tons in fiscal year 2022 alone. While drugs will continue to be smuggled with varying degrees of sophistication aboard a variety of types of smuggling vessels, the Coast Guard will continue to seize them.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard video by PO2 Paul Krug

Coast Guard Cutter Bertholf (WMSL 750) boarding teams interdict a low-profile go-fast vessel (LPV) while patrolling international waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean, seizing more than 3,100 pounds of suspected cocaine on Nov. 4, 2019. Purpose-built vessels like this are designed to smuggle large amounts of contraband while evading detection by law enforcement personnel due to their camouflaged appearance and low profile.

Credit: U.S. Coast Guard

Crew members from the Coast Guard Cutter Midgett (WMSL 757) interdict a suspected low-profile go-fast vessel in international waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean while transiting to their future homeport in Honolulu on July 31, 2019. The crew seized more than 4,600 pounds of cocaine from the suspected drug-smuggling vessel.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The National Coast Guard Museum will highlight the development of Coast Guard law enforcement technology in the Enforcers on the Seas wing on Deck 3 of the upcoming museum!