Born in the Canary Islands in 1862, Don (Mr.) Domingo Suarez y Rosa was part of the largest migratory wave of immigrants from the Canaries to Puerto Rico in the late 19th century.

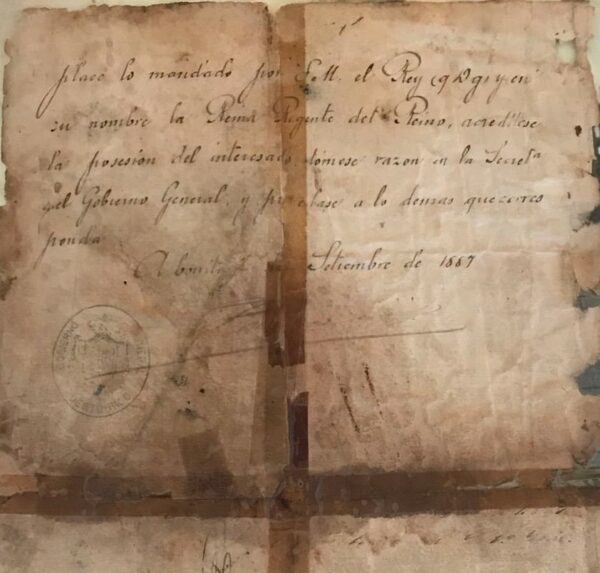

On March 6, 1887, after completing a rigorous entrance process and examination, Suarez was appointed by the King of Spain to the Caja de Muertos Lighthouse as a “Torrero 3ro,” or Towerman 3rd-Class. Lights requiring two towermen usually had a 1st-Class Towerman in charge and a 2nd-or 3rd-Class Towerman to assist. Suarez began as one of these assistant towermen. For Suarez, this appointment marked the beginning of a nearly 40-year career manning the lighthouses of Puerto Rico.

The requirements to become a Spanish towermen were stringent. Candidates had to be at least 21 years old, in “good physical health to perform their duties” and get “good conduct” and “good moral character” certifications from local authorities. Required knowledge included literacy, arithmetic and calculations, and first aid. Spanish authorities used longevity and performance to judge promotions and salary increases. Major lights had to have two towermen who usually lived with their families. Having their families reside at the lighthouse improved the towermen’s morale and performance, however, towermen of the same family or town were not generally permitted to man the same light.

In the 1860s, the Spanish Royal Government created the “Departamento de Ultramar” (Overseas Department) to manage the “Obras Publicas” or Public Works, for its overseas territories. The Departamento de Ultramar’s mission was improving land and maritime infrastructure in Spain’s Caribbean and Pacific island territories due to their growing commercial importance to Spain and the rest of the world.

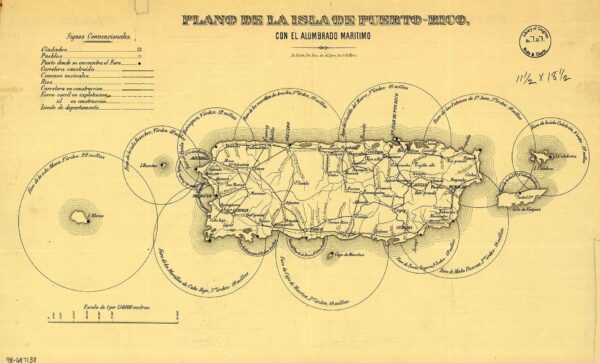

Between 1866 and 1869, Puerto Rico’s first supervisor for Public Works, Don Miguel Martinez de Campos y Anton, designed a land and maritime system for the island’s commercial and military infrastructure. His maritime lighting system, or “Alumbrado Maritimo,” consisted of “major” and a “minor” lighthouses. Major lighthouses had at least a 3rd-Order Fresnel lens and an 18-mile range. Minor lighthouses were equipped with 5th-or 6th-Order lenses with an eight-or 12-mile range. These lighthouses were built on remote bluffs, near dangerous shoals and major landmarks to warn mariners of hazards to navigation.

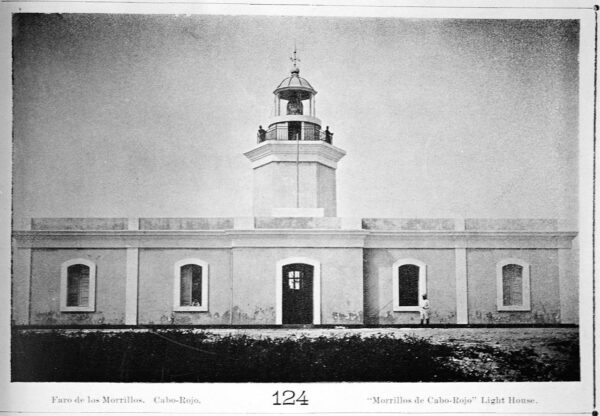

Miguel’s system was revised several times before 1876. That year, a major lighthouse was built in Fajardo, the easternmost tip of Puerto Rico facing the Leeward Islands. The Cabo Rojo Light followed in 1877, on the southwest tip of the island, and construction of Caja de Muertos Light, across from the port city of Ponce, followed soon after that.

The Cabo Rojo Lighthouse is located at the tip of southwestern Puerto Rico. This major light marked the turning point for maritime traffic entering and exiting the Mona Passage, the main channel between the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. The Mona Passage was an important commercial route for the export of sugar refined from cane grown in the southern valleys of Puerto Rico. Thus, Cabo Rojo had a 3rd-Order lens, with an 18-mile range, and quarters to house the families of two towermen.

Work at these lighthouses was a 24-hour responsibility. Upkeep of lighthouse machinery in the tropical weather required round-the-clock attention, including maintaining illumination and timing mechanisms. Before the use of kerosene fuel, this meant advancing the wick and winding the timing mechanisms. Because condensation fogged lenses, cleaning and polishing proved a never-ending task. In addition, towermen usually fished and tended gardens to augment their food supply. Their daily duties grew so burdensome, that towermen often hired local laborers to assist with lighthouse maintenance.

Considered property of the King of Spain, lighthouse buildings could double as militia quarters, jails, makeshift government courts or administrative centers. Other lighthouse duties included sheltering shipwrecked mariners and local citizens in case of natural disasters. Unlike lighthouses in North America, fog and ice are unknown in Puerto Rico, but the island has more dangerous natural foes. Earthquakes and hurricanes are common to this area having dire consequences for Puerto Rico’s maritime and coastal communities.

After his 1887 appointment, Suarez served for a brief period at Caja de Muertos Light before he was transferred to the Cabo Rojo Light. It was at Cabo Rojo that Suarez met his wife Dona Quintina Cruz and it is likely that his son, Domingo Suarez Cruz, was born at Cabo Rojo in 1888. The children of towermen often helped keep the lights, thus generations of towermen often came from the same families. Such was the case with Domingo Suarez whose son, Domingo Suarez Cruz, also manned the lighthouse.

In 1898, the Spanish American War saw Puerto Rico’s sovereignty transferred from Spain to the U.S. Many towermen serving in Spanish lighthouses transferred to the United States Lighthouse Service. When the lighthouses came under U.S. control, the Lighthouse Service repaired and converted them to kerosene fuel, enhancing their power and illumination. In 1899, during this transition, the Great Puerto Rico Hurricane struck the island as a Category 4 storm killing thousands of residents and rendering over 500,000 homeless. Suarez likely kept the light and assisted victims during and after this deadly storm.

After serving 12 years as a Spanish towerman, Suarez had become a keeper in the Lighthouse Service. Records show he remained at the Cabo Rojo Light until 1909. Around 1911, Suarez was transferred to Guanica Light where he served the longest of his assignments. Ten years earlier, the South Porto Rico Sugar Company of New Jersey had built one of the largest sugar mills in the world at Guanica Bay near the southwest corner of Puerto Rico. The Central de Guanica or Guanica Sugar Mill cultivated thousands of acres of cane fields and produced refined sugar for shipment.

Marking the entrance to Guanica Bay, Guanica Lighthouse proved instrumental in guiding ships to Guanica from the rest of the world. These vessels brought in equipment and supplies and loaded refined sugar for delivery to world markets. The Guanica Light was a smaller 6th-Order light with an eight-mile range and quarters to house one family. Initially, the Suarez family lived at Guanica Lighthouse. However, as his family grew, Suarez established a home in the village of Guanica.

It was at Guanica on a stormy night in 1914 that Domingo Suarez witnessed a pilot boat capsize beyond the mouth of the bay. Without hesitation, he jumped into the water and assisted the boat’s crew to safety, earning a U.S. Lighthouse Service commendation. That year, he was also recognized for heroism in the U.S. Lighthouse Service’s 9th District Annual Report, published by the Department of Commerce.

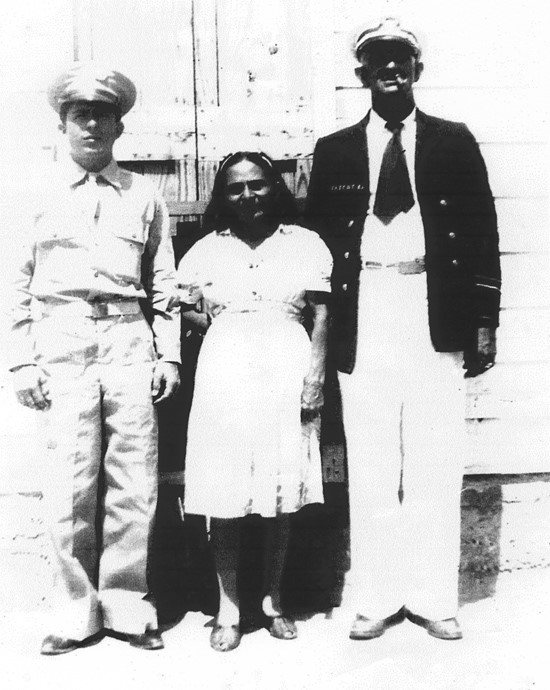

After this rescue, Suarez served over 10 more years at Guanica, retiring in 1925 after keeping the light for 38 years. Suarez’s son also served his lighthouse career at Guanica Light. Together, Suarez and his son’s time served at Guanica Light spanned 40 years. These proved the 40 most significant years in the life of the Guanica Lighthouse.

Like his father, Domingo Cruz kept the light through many natural disasters. Early in his career at Guanica, the Great Hurricane of 1928 (a.k.a., “Okeechobee Hurricane”) made landfall just east of the light as a Category 5 hurricane. Considered Puerto Rico’s worst storm of the 20th century, this hurricane left even more residents homeless than the catastrophic 1899 hurricane. Most certainly, Cruz manned the light while his family rode out the storm at their family home in Guanica.

There were no roads to Guanica Lighthouse, so all access between the family home and the light was by water. Domingo Suarez’s great granddaughter recounted:

“On weekends, we would travel across the bay in local wooden sailboats. It was very scary for me to go across the bay in those boats. My great grandfather [Domingo Suarez y Rosa] had died, but my grandfather [Domingo Suarez Cruz] was the towerman. Sometimes we would spend the weekends there. We slept in makeshift bunks and had a great time!”

In 1933, the U.S. Coast Guard assumed control from the Lighthouse Service for Puerto Rico’s lighthouses and aids-to-navigation and Domingo Cruz became a Coast Guardsman. By the 1940s, the Coast Guard transferred control to Puerto Rico’s commonwealth government. During World War II, Guanica’s sugar mill operations declined as did local shipping and the need for Guanica Lighthouse. Around 1950, Guanica Light was deactivated and replaced with an unmanned aid-to-navigation marking the bay entrance and range lights on land to keep mariners in line with the shipping channel. It was the end of an era. After well over 20 years of service at Guanica, Cruz retired. Nine years later he passed away at the age of 71.

Since its deactivation, Guanica Lighthouse’s buildings and grounds have decayed. Although it is registered as a National Park Service Historic Site and the local government has pledged to preserve the property, vandalism, weather and seismic activity have damaged the structure, perhaps beyond repair. It one of the last reminders of Puerto Rican towermen, such as Suarez and his son, who kept the light under the Spanish Crown and the United States.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum will have the opportunity to learn more about the incredible and diverse experiences of lighthouse keepers on in the Champions of Commerce wing on Deck04.