Joseph Gerczak was an enlisted Coast Guardsman who was killed in action while protecting his ship from attacking Japanese aircraft in World War II.

Gerczak was born in Philadelphia in 1922. He grew up in a rowhouse on North Cleaveland Street in the northern section of the city and had four siblings. As a teenager he was briefly arrested for “corner lounging.” He graduated from Simon Gratz High School in 1939 and worked as an apprentice machinist before enlisting in the Coast Guard on Sept. 26, 1942.

Gerczak attended basic training at Recruit Training Station Curtis Bay, Maryland. After graduation as a seaman apprentice, he briefly served on patrol boats based in Baltimore, including the CG-46015 and CG-75003. He was then assigned to a new Coast Guard-crewed Landing Ship, Tank, USS LST-66.

Landing Ship, Tanks

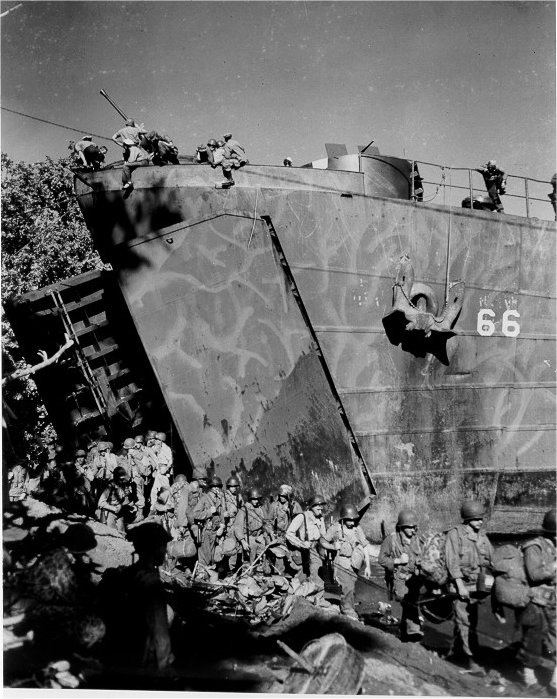

LST-66 was built at a shipyard in Jeffersonville, Indiana, on the banks of the Ohio River. Landing Ship, Tanks were the largest amphibious assault craft employed in World War II. It was 328 feet long with a crew of about 100, and they were designed to carry the heaviest invasion cargos or an entire company of troops to hostile beaches. LSTs could cross oceans, then run directly up on shore and discharge equipment, such as tanks, from their giant forward bow doors or flood their well decks to launch other vehicles like amphibious tractors while underway. Some were even configured to launch small aircraft. The United States eventually produced over 1,000 LSTs, many at inland shipyards. These ships were designated by number underscoring the nature of their industrial mass production. Many were even supplied to allied navies.

While extremely versatile, surprisingly durable, and critical for allied victory, duty on LSTs was not glamorous. The LSTs lacked the panache of a battleship, aircraft carrier, or the service’s Treasury-Class cutters. Despite the ability to ballast to enhance stability, their flat bottoms still made for unpleasant rolling in large seas. Just as their Navy and Coast Guard counterparts on the smaller Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) deprecatingly joked that the abbreviation LCI stood for “Lousy Civilian Idea,” LST crews said it stood for “Large, Slow Target,” among other nick names.

Little Joe and LST-66

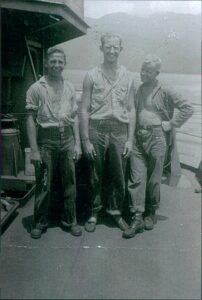

Reporting aboard LST-66 on April 3, 1943, while the ship was undergoing its final fitting out in New Orleans, Gerczak was one of the LST’s “plank owners.” Standing only 5 feet, 6 inches tall, Gerczak soon got the nickname “Little Joe.” He assisted in the onload of equipment, supplies, and countless other details for getting a ship ready for service. LST-66 was formally commissioned on April 12, with LT Howard White (USCGR) in command. A month of shakedowns, testing, and training followed, they then sailed for the South Pacific Theater.

When Gerczak came aboard LST-66, the vessel’s missions consisted of transporting cargo, training, and port calls in places like New Caledonia and Brisbane, Australia. They first saw combat on October 23, 1943, off Goodenough Island, New Guinea. It was supposed to be a training exercise with some Marines, but a lone Japanese plane suddenly appeared and dropped a bomb that exploded 100 yards from the ship. There was no damage or casualties and the plane escaped. A week later, on November 1, Gerczak advanced from seaman to signalman third class.

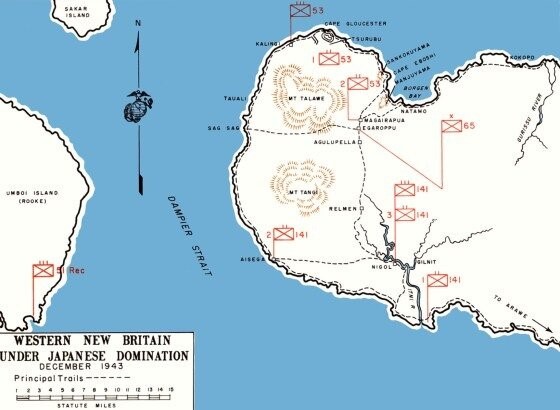

More cargo runs and training missions followed. Additional guns were loaded onboard for anti-aircraft defense the day after Thanksgiving. By early December, LST-66 was preparing for Operation Backhander, the Allied invasion of the island of New Britian. New Britain is a large island to the east of New Guinea. The operation is commonly referred to as the Battle of Cape Gloucester and was crucial for protecting Australia and enabling further Allied offensive operations against the Japanese Empire.

Sunday, December 26th, found LST-66 as part of Task Force 76 off Borgen Bay on the island of New Britian. It was one of 66 amphibious assault ships (including nine Coast Guard-manned LSTs) tasked with investing two beaches codenamed Yellow 1 and 2. The ships were protected by friendly aircraft, cruisers, and destroyers. LST-66 would be landing personnel of the First Marine Division, many of whom were veterans of previous hard fighting in Battle of Guadalcanal. The Marines and their equipment were crammed aboard anywhere that would fit and the LST’s crew manned their general quarters battle stations, anxious for its first combat action.

The cruisers began a heavy bombardment to soften up the landing beaches at 6 a.m. and the first troops landed at 7:45 a.m. The LSTs began beaching and unloading shortly thereafter, seeming to disembark Marines and equipment directly into the thick jungle. Operations were chaotic, but the landing appeared to be progressing well. There was no Japanese resistance on the ground, although a mid-morning air attack was disrupted by friendly fighter support.

LST-66 had just extracted itself from the beach when more Japanese aircraft appeared. This time they had penetrated friendly air cover. Gerczak’s Silver Star Medal citation describes what happened next:

When seven Japanese dive bombers suddenly attacked while his ship was in the bay awaiting the formation of the task unit then on the beach unloading cargo, Gerczak immediately manned his battle station and as the first to open fire when the planes came in and struck from starboard, poured his drums of ammunition into the attackers with unrelenting fury, blasting two from the sky and into the sea near his vessel. With his ship struck by bomb fragments, each bursting successively closer, he dauntlessly continued delivering a steady stream of bullets against the enemy until he was fatally struck down when a violent blast silenced his weapon and forced shrapnel into his gun shield. By his expert marksmanship, unwavering perseverance, and cool courage in the face of tremendous odds, he contributed materially to the success of this as well as previous assault and reinforcement landings in the New Guinea campaign and his constant devotion to duty throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

The shrapnel from the four near-miss bombs punched 149 holes in LST-66, all above the waterline, and started fires in the sickbay and galley that were quickly extinguished. Four other Coast Guardsmen were wounded and one Navy sailor that had missed his boat leaving the beach was also killed. LST-66 was credited with shooting down three Japanese planes, two of them by Gerczak before he died.

Joseph “Little Joe” Gerczak was 21 years old when he was killed in action. His Coast Guard career had lasted exactly 15 months. He was awarded the Purple Heart and Silver Star medals for his valor. His shipmates remembered him as a “good, wonderful, jovial kind of guy who was always positive” and, over time, their nickname for him of “Little Joe” evolved into a nickname for LST-66 itself as a tribute to his memory. His remains were interred at the United States Armed Forces cemetery in Finschafen, New Guinea.

Despite the loss of their shipmate, for the crew of LST-66, the war had only begun and there were many campaigns still to come. On Nov. 12, 1944, nearly a year after Gerczak’s death, the ship was operating off Leyte in the Philippine Islands when a Japanese aircraft crashed into the LST in a kamikaze attack. Five crewmembers were killed. Pharmacist Mate Robert Goldman delivered lifesaving medical care to his shipmates despite being badly burned, earning LST-66 the rare distinction of having two Fast Response Cutter namesakes hail from the same ship. LST-66 ended the war as the most-decorated LST serving in the Coast Guard.

After the war, Gerczak’s parents requested his remains be repatriated. He was re-interred at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania. In 2018, the Coast Guard named the Fast Response Cutter Joseph Gerczak (WPC-1126) in his honor. Its motto is “Unrelenting Courage.” Joseph Gerczak’s heroism and service, and those of his shipmates of LST-66, stand as a proud part of the long blue line.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: The history of the Coast Guard in World War II will be woven throughout the museum, but LST-66’s story, specifically will be located on Deck 3, as part of Defenders of our Nation.