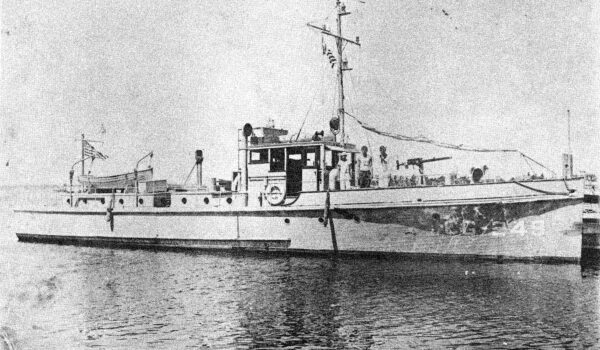

On the morning of Sunday, Aug. 7, 1927, the 75-foot, wooden-hulled Coast Guard Patrol Boat (PB), CG-249, departed Coast Guard Base Six, Fort Lauderdale, Florida and headed roughly eastward at its most economical speed of 10 miles per hour.

Instead of the usual alcohol interdiction operations that occupied CG-249’s underway hours in the Florida Straits, the day’s assignment was a simple interagency support mission to transport Secret Service Agent Robert K. Webster to Bimini—an island on the western edge of The Bahamas. Once there, Webster would investigate the passing of counterfeit U.S. $50 silver certificates, likely used by smugglers to buy liquor in Bimini’s freewheeling alcohol market. Meanwhile, CG-249’s seven-person crew would enjoy a relaxing overnight liberty, during which they could legally drink—a pastime that had been restricted in the U.S. since the start of Prohibition in January 1920. The next morning, they would return to Fort Lauderdale and resume the grind of chasing rum runners.

Every one of the PB’s crew were experienced rum-busters. Even the youngest, Seaman First Class Hal Caudle, had participated in several busts—one of which had involved an exchange of gunfire with smugglers—but they had been together as a crew for only a few short months.

Just five months earlier, after two incidents involving corruption, the 249’s previous officer-in-charge (OIC), Chief Warrant Officer Joseph Delamar and his entire crew had been dismissed from the Coast Guard or reassigned. The first incident involved allowing two smugglers to escape after arrest, while the second involved consuming and selling seized liquor, blocking narcotics agents from accessing a seized vessel, and threatening narcotics agents in the performance of their duties. Chief Warrant Officer Sidney C. Sanderlin had been appointed from the enlisted ranks in February and placed in charge of the CG-249 barely a month later. In five short months, he had melded the new crew into an efficient interdiction machine.

So it was no surprise, when at about 1 pm, with CG-249 about 34 miles out of Fort Lauderdale, Petty Officer 1st Class Frank Tuten, a boatswain’s mate, sighted a white, open cockpit 30-foot fishing vessel heading on a reciprocal course from Bimini—he immediately knew it was a smuggler. He called Sanderlin to the pilot house. Together, they examined the boat through binoculars: Florida registration V-13997; no fishing gear evident; riding low in the water and coming from a well-known departure point for smugglers. Sanderlin decided to check out the boat and apologized to Webster for the delay it would cause. Webster was not put out all, rather he was eager to see the Coast Guard in action.

Tuten hurried below to fetch a Springfield bolt action .30-06 rifle from the armory while Sanderlin ordered a turn to port and increased speed to intercept. The mission had quickly changed from a simple transport run to a serious interdiction.

As CG-249 closed on its target, Sanderlin fired three individual tracer rounds from the Springfield across the boat’s bow. The two men aboard the V-13997 ignored the first two glowing projectiles, but with nowhere to go and CG-249 rapidly closing, they throttled down after the third round splashed just forward of their bow.

With CG-249 a few yards from the V-13977, Sanderlin shouted standard pre-boarding questions. He was unsatisfied with the answers that they had departed from Miami, fished for a few days near Bimini, and were now headed back to Miami. Given their initial refusal to stop, Sanderlin was now certain the two men were smuggling liquor.

Caudle removed one of the three Colt .45 pistols from the “ready rack” extending several feet along the starboard bulkhead of the pilot house, just forward of the starboard door. Determined to be ready if things went south, he inserted a magazine, chambered a round, and re-holstered the pistol on his right hip. Sanderlin also grabbed a pistol, but haphazardly thrust it into his right trouser pocket. Until this point, the Coast Guardsmen had functioned like a well-oiled machine, with each member performing his task smoothly and efficiently. That machine was about to break down as Sanderlin himself initiated a pattern of deadly disregard for boarding protocol and prisoner control.

Tuten had taken over the helm. And maneuvered CG-249 against the other boat’s port side. Lines were passed and the boats were secured together, with the bow of the V-13997 reaching about midship of the CG-249.

Sanderlin jumped aboard the suspected smuggler by himself, brushed past the two suspects, and proceeded directly to the hatch on the boat’s focsle. He lifted it, and immediately saw cases of alcohol. The total would later be determined to be 20 ½ cases—a small load compared to the several hundred cases often carried by smugglers, but still illegal.

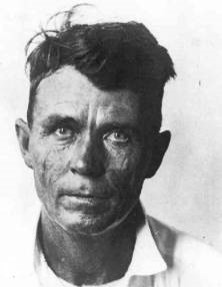

Both smugglers, James Horace Alderman, and Robert E. Weech, appeared to take their arrest well. They offered no resistance and cooperated as Sanderlin frisked them for weapons. When Sanderlin then directed them to follow him back aboard CG-249, Alderman, asked if he could take a moment to grab a few valuables. He played on the Coast Guardsman’s sympathies, claiming his valuables would otherwise “disappear” as soon as his boat was turned over to customs officers. Sanderlin consented, and Alderman was allowed to hang back, unmonitored. By today’s law enforcement protocols, the failure to handcuff or guard prisoners would be considered major lapse in judgment, but Prohibition was a different time.

Almost all smugglers could be expected to try their hardest to outrun the Coast Guard, but if they otherwise did not resist during pursuit, they generally accepted their fates good naturedly once overhauled. This was especially true in the waters off Florida, where the penalties handed down by the courts for rum running were usually light. Given a small load and a first offense, smugglers could expect to get off easy—the seizure of their boat, a fine, and perhaps even no jail time.

But Alderman was by no means a first-time offender. He had already done federal prison time for liquor smuggling, been convicted of aggravated assault, been fined for violating fish and game laws, and was currently out on bond for smuggling undocumented aliens. He definitely could not expect leniency.

Alderman also had a chip on his shoulder. He believed that several smugglers had been recently murdered in cold blood while fleeing the Coast Guard, and was convinced that law enforcement in general, and the Coast Guard in particular, was out to ruin him. While the Coast Guardsmen had no way of knowing this and expected no trouble, failure to secure the prisoners was still a gross lapse in security.

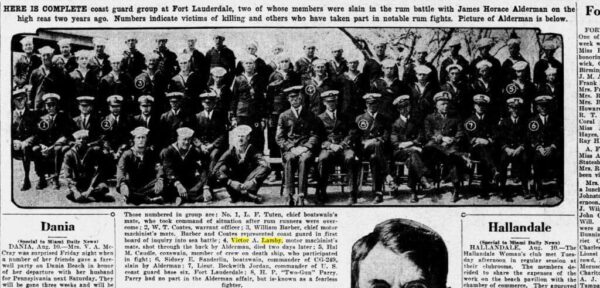

When Alderman crossed over to the boat, he paused at the starboard pilot house door. All weapons had been returned to the Armory or ready rack, and most of the Coast Guard crew had stripped to T-shirts or bare chests and were passing cases of alcohol to CG-249. Sanderlin had opened the radio cabinet at the rear, port-side bulkhead of the pilot house and was bent over the radio in preparation to informing Base Six of the seizure and his plan to send the seized vessel, crewed by Petty Officer 1st Class Victor Lamby, a motorman machinist mate, and Petty Officer 2nd Class Johnnie Robinson, a boatswain’s mate, back to Base Six, while CG-249, with the contraband liquor aboard, continued with its transport mission.

Alderman suddenly produced a pistol and shot Sanderlin through the heart from behind, at a range of only a few feet. Sanderlin was dead before hitting the deck.

Lamby, who had been speaking with Webster just forward of the pilot house, saw what happened. He ducked and ran aft in a crouch to stay below window level, praying that Alderman would not shoot through the plywood bulkhead. Lamby reached the aft hatch and started to descend the ladder hoping to make his way to the armory to retrieve a weapon, but Alderman fired. The bullet struck Lamby in the chest, nicked his lung, shattered part of a vertebrae, and lodged against his spine. He fell into the engine room. Despite being paralyzed from the waist down, he dragged himself to temporary safety between the engines.

Alderman then rounded up Webster and the remaining Coast Guardsmen and herded them to the stern of his boat. He gave Weech a pistol and ordered him to finish off Lamby and to prepare CG-249 for destruction by breaking the fuel lines. Alderman planned to burn CG-249 to the waterline—with the Coast Guardsmen aboard. Since explosions and fires were not rare events aboard the gasoline-powered vessels of the period, his plan might have succeeded.

Although Weech disabled the fuel lines, he refused to shoot Lamby or set afire CG-249 with the Coast Guardsmen aboard. Alderman threatened to kill Weech if he didn’t play along, then sent him below to get their boat engine started.

When Alderman became momentarily distracted shouting down to Weech in the engine room, Webster—a decorated World War I Army sergeant—lowered his hands and charged; the remaining five Coast Guardsmen were a split second behind him. Webster almost got his hands on the gun in Alderman’s right hand when Alderman shot him through the heart. With his second pistol, Alderman shot acting ship’s cook Seaman Jody Hollingsworth in the shoulder. The bullet struck bone and deflected upward, shattering Hollingsworth’s jaw and destroying his right eye. Hollingsworth dropped overboard as the remaining Coast Guardsmen fell on Alderman like the furies, bearing him to the deck in a mass of struggling bodies. They wrestled the pistols from his grip, and then beat and stabbed him with the pistols, a paint scraper, and an icepick until he lost consciousness.

Webster almost got his hands on the gun in Alderman’s right hand when Alderman shot him through the heart. With his second pistol, Alderman shot acting ship’s cook Seman Jody Hollingsworth in the shoulder. The bullet struck bone and deflected upward, shattering Hollingsworth’s jaw and destroying his right eye.

As the men recovered from their battle fury, Robinson remembered Weech in the engine room. He took a pistol and rushed forward. Weech bolted on his approach, but Robinson caught him, manhandled him to the side and tossed him overboard. When Weech would rise to the surface, Robinson would strike him in the head with an oar, driving him under. He was stopped by Tuten, who had asserted command and made a conscious decision to bring the rum runners back alive. The Coast Guardsmen pulled Weech from the water, dragged him aboard CG-249, and handcuffed him to the 1-inch gun mount, alongside a semiconscious, battered, and bloodied Alderman.

Meanwhile, Hollingsworth had also been rescued. Despite his wounds, he had miraculously remained conscious and treaded water the entire time. While several of the men carefully moved the mortally wounded Lamby topside from the stiflingly hot Jodie Hollingsworth engine room, Tuten radioed a distress call to Base Six. Help arrived in less than an hour, and while CG-249 was being repaired, the wounded men were rushed to the hospital.

Jodie Hollingsworth would survive his wounds, although disfigured and disabled for life. Victor Lamby appeared to be recovering after removal of the bullet lodged against his spine, however, three days later he succumbed to pneumonia from an infection in his wounded lung.

Alderman and Weech were originally charged with murder, but their case was soon severed. Weech was prosecuted on a lesser charge since he acted under duress. Alderman was found guilty of both murders on Jan. 28, 1928, and sentenced to death. On Aug. 17, 1929, after exhausting appeals, he became the first and only person ever hanged aboard a Coast Guard base.

This case illustrates that even a well-trained, experienced crew can be undone by overconfidence. Inattention to the risks of a routine arrest can lead to disaster. Only extreme bravery in the face of certain death enabled the crew of CG-249 to retrieve the situation and forestall an even greater tragedy.

National Coast Guard Museum insider tip: Visitors to the National Coast Guard Museum Will be able to learn more about this and other harrowing stories from prohibition in the Rum Wars exhibit on Deck03.